[ad_1]

KATHERINE MCMAHON/ARTNEWS

So many books, so little time! Yet we read what we can and find ourselves enriched as a result. In tribute to some (but by no means all) of the books we turned to when in want or need of learning, here’s a list of favorites from 2018. —The Editors

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, 1514.

COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I, Mitchell B. Merback (Zone Books/MIT Press)

This deep dive into a 1514 woodcut by Albrecht Dürer benefits from all that is wondrous and perplexing about a work of art that—even more than most—makes elusiveness a sort of parlor game. That serves as part of a thesis put forth by Mitchell B. Merback, an art historian at Johns Hopkins University who sees in Dürer’s mysterious arrangement of pensive figures and cosmic objects what might have been purposefully conceived as a tool for mental exercise. What is going on with that abstract polyhedron standing like a monolith for no apparent reason? How about the decorative “Jupiter square” wall-hanging in which rows of numbers tallied in any direction (vertical, horizontal, diagonal) add up to 34? And what’s up with the bat flying with a banner carrying the artwork’s title in from out of the sky? All of this gets worked out in the midst of historical context expanded by the presence of medieval poison paintings (for which pigments were mixed using toxic agents) and so much more. What proves resoundingly clear is that, in Dürer’s age, beholding a work of art was an active rather than passive activity. Count that as a lesson to consider. —Andy Battaglia

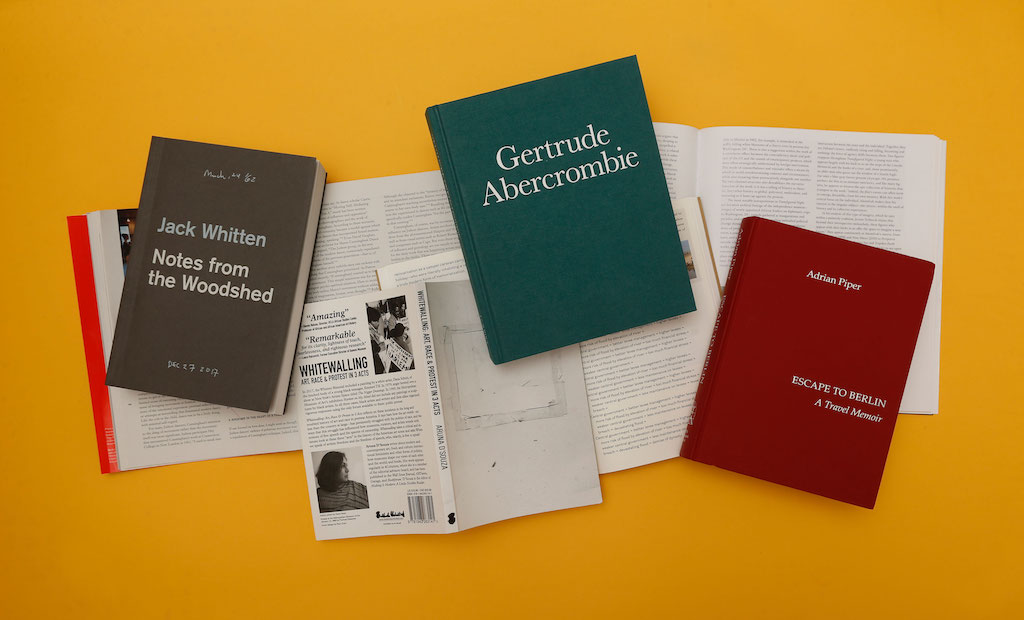

Jack Whitten: Notes from the Woodshed, ed. Katy Siegel (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

At the end of the titular essay in Notes from the Woodshed, Jack Whitten writes, “We must learn to re-structure the environment which in turn exercises our minds.” I can say with confidence that, as I read Whitten’s own writings about his work (many of them culled from journals dating between 1962 and 2017), I could feel my mind being restructured. Lovingly assembled by Katy Siegel, this book features meditations on painting after Abstract Expressionism, photonics (the study of light particles), feminism, racism, Cretan sculpture, and identity. Many are tender, thoughtful, and totally engrossing—and so endearing and funny. It’s a lot to take in, and I get the feeling that Whitten, who died earlier this year at 77, knew that. As he put it in one diary entry from the early ’70s: “This shit is complicated!” —Alex Greenberger

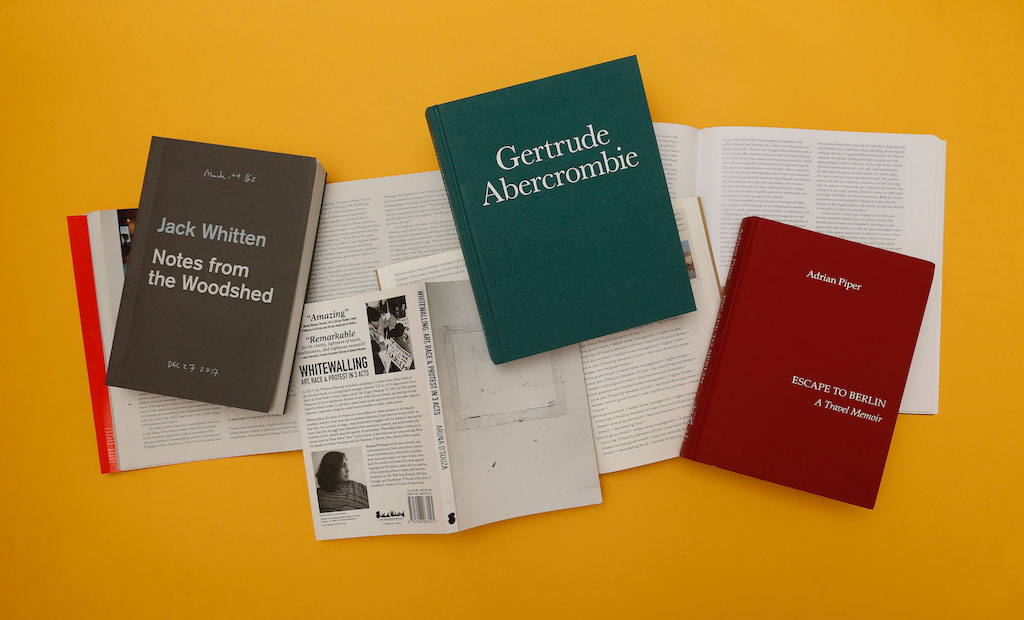

Garage, Olivia Erlanger & Luis Ortega Govela (MIT Press)

Garage, Olivia Erlanger & Luis Ortega Govela (MIT Press)

As illustrated in this thought-provoking deconstruction of an architectural structure that morphed into a creative space within the context of suburban America, the garage can be a place where legendary bands rehearsed their first tunes and billion-dollar tech companies got their start. In the words of the authors, “The garage was an aboveground underground, offering both a safe space for withdrawal and a stage for participation—opportunities for isolation or empowerment.” —Katherine McMahon

Vile Days: The Village Voice Art Columns, 1985–1988, Gary Indiana (Semiotexte)

The year that saw the closure of the Village Voice also delivered this choice reminder of one of its many glories: the weekly pieces that Gary Indiana penned on the New York art scene in the mid-1980s. Even some of the sharpest quick-deadline criticism goes dull with time—nothing wrong with that, necessarily, if it gets the job done in the moment—but Indiana’s articles still make for invigorating reading; they’re by turns caustic and charming, poetic and personal. Hanne Darboven is “the ample ghost in her own machine,” Christopher Wool abstractions “exercise an almost hideous power,” and Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981) “is a physically abrasive, hateful piece of art.” And then there are his delicious asides and experiments, whether discussing the “hundreds of boorish, sexually desperate drunken American sailors” running around Venice during the biennale or writing a column as a numbered list. Number 12 sums up the joyous fearlessness of his incredible run: “If I made a record based on my experiences as an art critic I would call it I Don’t Care If You Never Forgive Me, b/w Fuck You If You Can’t Take a Joke (Yourself).” —Andrew Russeth

Gertrude Abercrombie, ed. Dan Nadel (Karma)

When the downtown gallery and bookseller Karma put on New York’s first exhibition in more than a half-century of the inimitable American surrealist Gertrude Abercrombie, the walls teemed with the artist’s eerie—and charming—paintings of moons, cats, owls, shells, oceans, barren landscapes, ostrich eggs, and more. The accompanying catalogue offers an intimate look at Abercrombie’s life and career (via essays by Robert Storr, Susan Weininger, and Robert Cozzolino), as well as photos of Abercrombie stationed among the many curiosities in her Chicago home or engaging with her friends. Also featured are a transcript of a 1977 radio interview with Studs Terkel and excerpts from Abercrcombie’s own Joke Book, a journal filled with encounters with others as well as anecdotes about her family. In one colorful entry, she wrote, “A man, a well-known scholar—he worked on the atom-bomb project—asked me why I painted the moon in a room, and I said, ‘Yes it is a puzzle. Why is it anywhere?’ ” —Claire Selvin

Gertrude Abercrombie, Untitled (Blue Screen, Black Cat, Print of Same), 1945.

COURTESY KARMA

Esopus Drawings, Tod Lippy (Esopus)

After 15 years and 25 issues filled with an almost unfathomable range of art, archival materials, unclassifiable delights, and, not least, types of paper, the beloved Esopus magazine decided to suspend its print production this year, and its founder marked the occasion with this beautiful, melancholy compilation of his drawings. Printed (disguised, really) as a Bristol sketchbook, with its unmissable yellow cover and a piece of masking tape bearing its title, the book contains 25 graphite renderings that Lippy made, all related to his long labor of love. A fresh box with copies of the 18th issue is the subject of one; a wall covered with reader correspondence is that of another. It’s an artifact of a life well-lived. And it’s important to add that Lippy remains active: Esopus magazine is on hiatus, but Esopus the organization is still operating. I can’t wait to see what Lippy cooks up next. —Andrew Russeth

Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, David Wojnarowicz (Vintage)

This isn’t a new book (it’s from 1991), but it was new to me when I picked it up in advance of the Whitney Museum’s David Wojnarowicz retrospective, which was my favorite show I saw all year—and one that will stick with me for the rest of my life. In his writing, Wojnarowicz oscillates between macabre humor and fiery anguish, pulling at the heart while stomping on it, too. Olivia Laing, in her 2016 book Lonely City, summarized what makes Close To The Knives so special: “In all his writing there is a stepping back and forth between different kinds of material, some very dark and full of disorder, but containing astonishing spaces of lightness, loveliness, and strangeness. He possessed an openness that was in itself beautiful, though sometimes wondered if he was only capable of reproducing the ugliness he’d seen.” I credit Wojnarowicz’s openness with why I could only stare at a wall for hours after I left the Whitney one fateful day in July. —Annie Armstrong

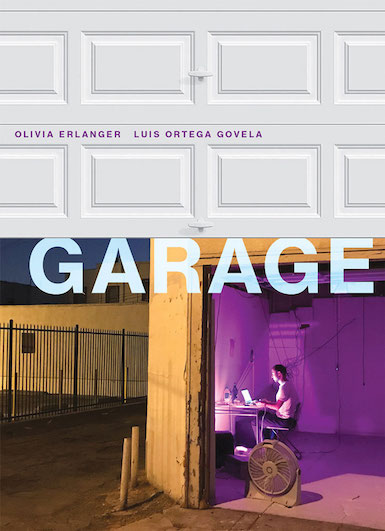

Broken Music, ed. Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier (Primary Information)

Broken Music, ed. Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier (Primary Information)

From the archival aficionados at Primary Information comes this invaluable volume documenting artist’s records and objects that circulate in the fertile interzone between what too often gets overdetermined as art in one corner and music in another. There’s a flexidisc of Milan Knizak’s Broken Music (a composition that leant the book its title) at the beginning, and so many riches follow, from a historical treatment of the earliest recording techniques to an essay on music by Jean Dubuffet to (most importantly) a compendium of “artists’ recordworks” ranging from Vito Acconci on vinyl to a spinning dummy sculpture with sound-making marbles in its head by Ben Vautier. The book was compiled in Germany by the sound-art gallerist Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier in 1989, and it remains an important resource nearly 30 years later. —Andy Battaglia

Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts, Aruna D’Souza (Badlands Unlimited)

Make no mistake: Though Whitewalling is just 147 pages long, it’s something of an epic project that warrants reading for years down the line. The book focuses on three seemingly unrelated controversies surrounding Dana Schutz’s Open Casket at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, the 1979 “Nigger Drawings” show at New York’s Artists Space, and a 1969 exhibition about Harlem at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Each was protested and scrutinized, and all served as evidence of divisions between white and black members of the so-called art world. Who is allowed to represent whom, and why? What good can an open letter do? Is protesting at art institutions futile or necessary, or both? Aruna D’Souza’s detail-oriented recounting broaches these questions and then some. —Alex Greenberger

Houses, Katherine Bernhardt (Karma)

In contrast to Katherine Bernhardt’s neon-hued paintings, this book of black-and-white sumi-e ink drawings is an ode to modernist homes of the Hamptons, completed during Bernhardt’s residency at the Elaine de Kooning House in 2016. Dedicated to the late Julie Taubman, the founder of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, it is a graphic collection of Bernhardt’s ruminations on some of the architectural touchstones of the East End, all created on the same table that de Kooning worked on. —Katherine McMahon

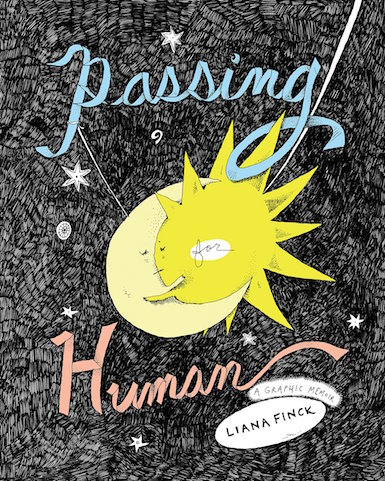

Passing for Human: A Graphic Memoir, Liana Finck (Random House)

Passing for Human: A Graphic Memoir, Liana Finck (Random House)

Passing for Human is a tender meditation on self that Liana Finck—an illustrator known for her contributions to the New Yorker, the Awl, and Catapult—has called “a neurological coming-of-age story.” Through humorous, direct, and personal drawings, the book traces Finck’s search for her “shadow,” which she considers a piece of herself that’s missing. “I draw because once, I lost something—and by drawing I will find it,” she writes. The journey takes the reader through the author’s childhood and her later struggles as an artist, but, in a bigger sense, Passing for Human serves as a comment on the ways in which people in general and women in particular can be merciful to themselves in the face of anxiety, self-doubt, and other feelings. —Claire Selvin

Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir, Adrian Piper (Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin)

If you were not sated this year by the Adrian Piper retrospective at MoMA, a beautifully illustrated catalogue to go along with it, and a new book of essays about her work, there is this book, which bills itself as a “travel memoir” but functions more as a long-form explanation for why Piper left the United States for good. Critics do a lot of speaking for Piper, so I was glad to see her put into writing her own account of self-exile. I was glad, too, to see it done with such style. Escape to Berlin merges poetry, Kantian philosophy, Hindu scripture, and much more into a tricky statement about how to maintain your identity when everyone wants to define it for you. Some might find it bitterly humorous, too. As Piper puts it, speaking of one of her masterpieces in which she renounced her blackness, “It is only funny if you are sane enough to get the joke.” —Alex Greenberger

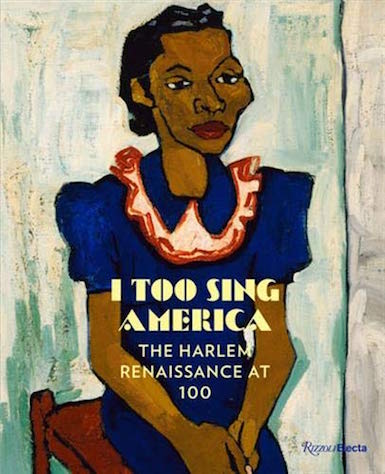

I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance at 100, Wil Haygood (Rizzoli Becta)

I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance at 100, Wil Haygood (Rizzoli Becta)

One measure of an exhibition catalogue’s quality is the degree to which it makes you want to go see the exhibition. In the case of this volume, let us just say that, since picking it up, I have been wracked with pain that I have not been able to visit the Columbus Museum of Art to catch the show it accompanies, which runs through January 20. It is a sumptuously illustrated tome, with reproductions of pieces, variously iconic and little-known, by Palmer Hayden, Loïs Mailou Jones, Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage, Horace Pippin, and many, many more. Haygood is a biographer and journalist (famed for writing the story that became the film The Butler), and he’s accomplished the rare feat of weaving together rich scholarship with luminous prose. Including contributions from a variety of experts, it takes an expansive view of its subject, looking not only at visual art but vernacular photography, writing, and periodicals of the movement. “The Harlem Renaissance lives,” Haygood writes. “It sings. It continues to do its part to explain America to itself, and also to the world.” This book is a superb vehicle for that remarkable story. —Andrew Russeth

Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of California Press)

A few months back, on a day when I really needed it (oh, the moods do rise and fall), I picked up this book—the catalogue for an exhibition at the de Young Arts Museum in San Francisco and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—and communed through the ages. It’s easy to take for granted or otherwise doltishly forget, but to connect with art made hundreds and thousands of years ago is . . . well, it’s really something! I didn’t get to see the exhibition in California, but thanks to the virtues of the turning page, I learned a lot about a city and a culture I’d known close to nothing about. And I came away from it feeling grateful to the artists there for doing the work they had done. —Andy Battaglia

[ad_2]

Source link