[ad_1]

Cover art for Alexander Provan’s Measuring Device With Organs.

Music is art in all cases, and any energy devoted to segregation is misspent. But then, at the same time, there are manifestations of music that make the unity more clear—easier to acknowledge, accept, and affirm. Yet even then, subjectivity enters in, such that the notion of distinctions starts to reveal itself as farce. And then we arrive once again at the essential truth that we started with: music is art—and on and on and on.

I listened to lots this year, with different purposes in mind. Here are some of my favorite releases that might slot more easily than others as “art.” (Not that it could be otherwise!)

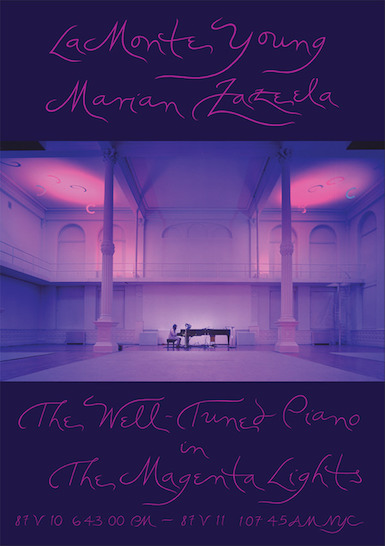

La Monte Young & Marian Zazeela, The Well-Tuned Piano in The Magenta Lights (MELA)

La Monte Young & Marian Zazeela, The Well-Tuned Piano in The Magenta Lights (MELA)

For listeners of a certain disposition, it can be hard not to turn intensely meditative when in the presence of the music of La Monte Young, whether in the immersive environs of his long-running Lower Manhattan installation Dream House (conceived with his partner Marian Zazeela) or via the scant few recordings of his minimalist masterworks that circulate. The holy grail is The Well-Tuned Piano, and after years out of print, a 1987 recording of the piece filmed within the luminous setting of Zazeela’s Magenta Lights appeared on a recently reissued DVD. The music—played by way of a piano tuned to just intonation, to produce deep harmonics and otherworldly overtones—lasts for more than six hours, and it’s enough to make certain of us want to never be far from its effects.

Brian Eno, Music for Installations (Universal)

Collecting ambient music by a formative but still evolving master of the form, this luxe box set—in 6xCD or 9xLP incarnations, each with a 64-page book—traffics in the kind of sounds you put on to pay attention, often to other things. The offerings date back to 1985 and feature some of Eno’s so-called generative music along with sounds integral to multimedia works like his 77 Million Paintings (a slowly spinning kaleidoscope of digital imagery projected on screens) and exhibitions of art of different kinds. The packaging is nice, with discs that pull out on trays and a book that seems somehow to have glass for a cover. But the sounds are the star of a show that suits Eno’s aspiration to, as he writes in the book, “make listening experiences similar to sitting by a river; an experience of continual change and constancy at the same time.”

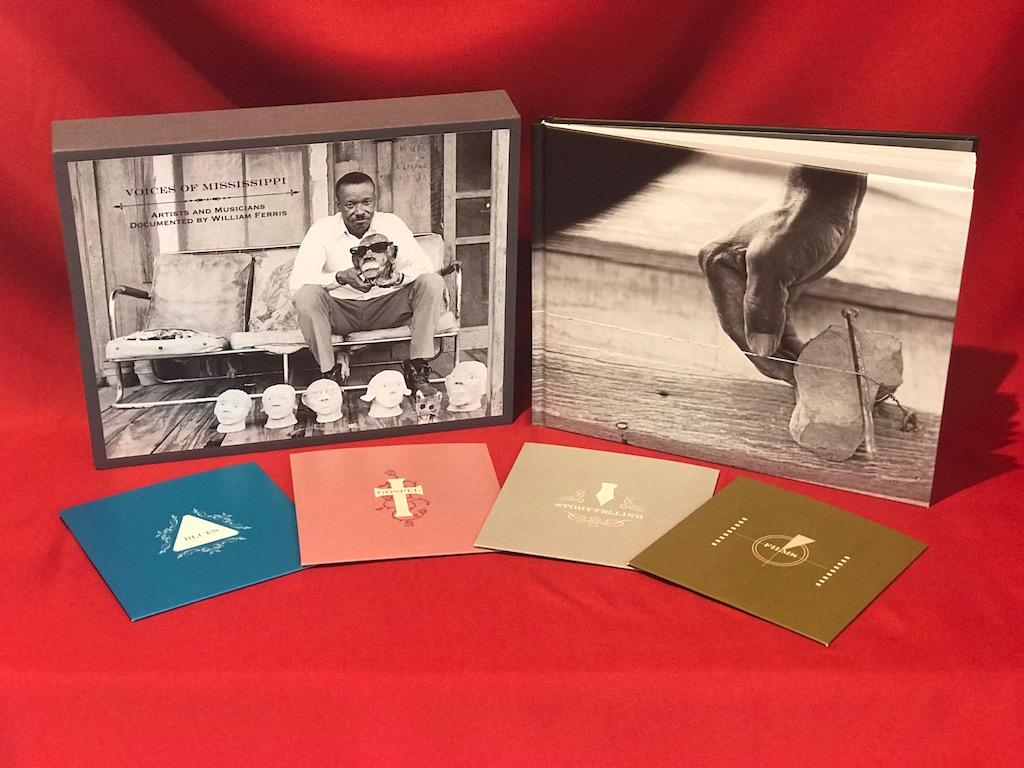

Voices of Mississippi: Artists and Musicians Documented by William Ferris (Dust-to-Digital)

One of the latest gifts from the unsurpassable Atlanta-based archival label Dust-to-Digital (the source of so much valuable mining of crucial and often unsung pasts), this box assembles recordings of old blues, gospel, and storytelling dating back to the 1960s, as well as documentary films made by William Ferris, the storied folklorist and former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. The music is great (anyone who has not heard blues by Scott Dunbar is in for a riotous treat), and the context it’s set in is reverent and worthy. The seven short films compiled on a DVD feature titles like Hush Hoggies Hush: Tom Johnson’s Praying Pigs and offer spirited sights like congregants of the late great party-starter Otha Turner making biscuits, blowing fifes, and banging drums.

Alexander Provan, Measuring Device With Organs (Triple Canopy)

From the medium-melding mind of Triple Canopy editor Alexander Provan, this more than a little unusual record (released as both an LP and digital files) plays as a mix of spoken-word story and aurally adventurous radio play. The premise hovers around the presence of a special listener undertaking audio tests for the sake of “sound quality assessment,” and—in a surreal mingling of aspects of David Foster Wallace’s short story “Mister Squishy” and outré sound collage—the proceedings get stranger and stranger. The writing is sharp—to wit, a passage about “Sirius XM, whose proprietary compression technique made the doubled, distorted, ferociously picked blues riffs of Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Oh Well’ sound like alarm clocks going off in an aquarium.” And then another regarding “an obsessive, antisocial, middle-aged gearhead trapped in a skinny little boy’s increasingly ghostly body.” But it’s a tribute to the imaginativeness of the project that writing is just one of many practices at play.

Sophie, Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides (Transgressive/Future Classic)

One of the year’s best artifacts of future-music left behind for the rest of us to catch up to is this initially heartrending and ultimately mind-melting album from an artist affiliated with the electronic pop label PC Music. Anyone who has not yet heard the gorgeous album-opener “It’s Okay to Cry,” get thee to headphones fast. And then there’s all the rest, which ranges from dark and fractious technicolor fantasias to ashen ambience and back again.

Simone Forti, Al Di Là (Saltern)

Drawn from a show titled “Sounding” at the Box in Los Angeles, this compilation by the dancer/choreographer/etc. Simone Forti features aural artworks dating from the 1960s to the ’80s. One is a sung song accompanied by a shaking can of nails, as performed in Yoko Ono’s loft in 1961; another is the result of “a slide whistle equipped with a stylus.” The four-part track “Bottom” includes vocals by La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, and then there’s “Dal Di Là,” about which Forti writes in the liner notes: “I made this song towards the end of a period of performing stoned on weed. It roughly translates: I’m awaiting a song from afar, from afar, a song of goodbye from afar. For now I’ve seen the game I was playing, slowly leaving the earth and drifting far among the stars.”

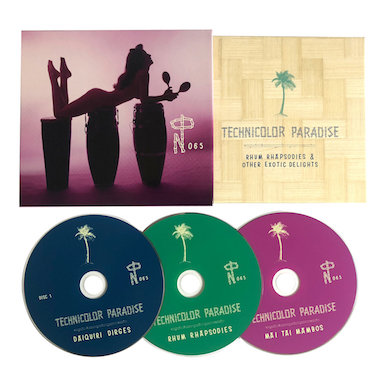

Technicolor Paradise: Rhum Rhapsodies & Other Exotic Delights (Numero Group)

Technicolor Paradise: Rhum Rhapsodies & Other Exotic Delights (Numero Group)

There’s not much of an art angle to this one, but Technicolor Paradise is probably what I listened to more than anything else this year. Across three volumes, a teeming mix of atmospheric cocktail music and early surf-inflected rock ‘n’ roll from the 1950s and ’60s morphs into a sort of dream world that is tranquil and transporting by turns. It does not lack for problematic aspects: “exotic” is in the title, and you can do the math from there. But then there’s something wide-eyed and earnest about it all, too—the sound of young people at the turn of the 20th century imagining far-flung parts of a world that was only just then beginning to come into full view.

Catherine Christer Hennix, Selected Early Keyboard Works (Blank Forms/Empty Editions)

Under-appreciated but making her way into the history in which she deserves to loom large, Catherine Christer Hennix made the rehearsal tapes from which this double album was assembled in 1976, on keyboards tuned to just intonation. Much of the music meanders, with a thinking-out-loud quality that is captivating to follow, and the droning quality of “The Well-Tuned Marimba” finds some interesting vistas on which to settle and stare out at the horizon. The release of these unheard recordings coincided with “Thresholds of Perception,” a show at Empty Gallery in Hong Kong (co-curated with Blank Forms) that I was lucky to see. Hennix performed two concerts there and exhibited probing and prescient visual work that has barely been shown in the decades since it was made. With two volumes of Hennix’s writings to be published next year, here’s hoping there’s more due attention to come.

Tashi Wada with Yoshi Wada and Friends, FRKWYS Vol. 14 – Nue (RVNG Intl.)

The ongoing “FRKWYS” series from the excellent New York label RVNG Intl. pairs younger artists with older beacons of influence, and this one kept the connection close with a Fluxus-affiliated father and his enterprising son. The older Yoshi Wada was active in the ’60s with George Maciunas and his crew, and the younger Tashi Wada has worked with contemporaries including Julia Holter (who appears here) and the magisterial cellist Charles Curtis, among others. The sounds on Nue tend toward the deep and the meditational, with timbres and tones from bagpipes, keyboards, and lots of things that are not so easily discernible in the kind of pliant mindstates they invite.

Lonnie Holley, MITH (Jagjaguwar)

The great Alabama-born artist Lonnie Holley made a real soul-stirrer in MITH, which places him and his wonderfully warbly voice atop keyboards that follow his cues to quiver and quaver with warmth and personality. “I’m a suspect / in America,” he sings at the start, before panning back to take in a more cosmic context that makes the kinds of earthly plight he surveys seem all the more depressing—but also, maybe, all the more susceptible to change.

Autechre, NTS Sessions 1-4 (Warp)|

Autechre, NTS Sessions 1-4 (Warp)|

Having been as abstract as abstraction could be since their formative days in the early ’90s, Autechre would seem to have exhausted all the avenues for further abstraction. But it turns out that duration serves them well—as evidenced by this eight-hour compendium of music made during a residency on NTS Radio. The sinewy rhythms and overall sound-design are out of this world, and beyond the simple novelty of the length (eight hours, you say?!), there’s a strong case to be made for Autechre’s music being well-served by time to wander, wait, and then go out wandering again. But then there’s the fact that, after 35 tracks measuring around 10 and 20 minutes long, the final piece times out at no less than 58:21. For some reason I can’t quite fully figure, I found that to be funnier than anything I came across this year. Seems like a suitable send-off to 2018.

[ad_2]

Source link