[ad_1]

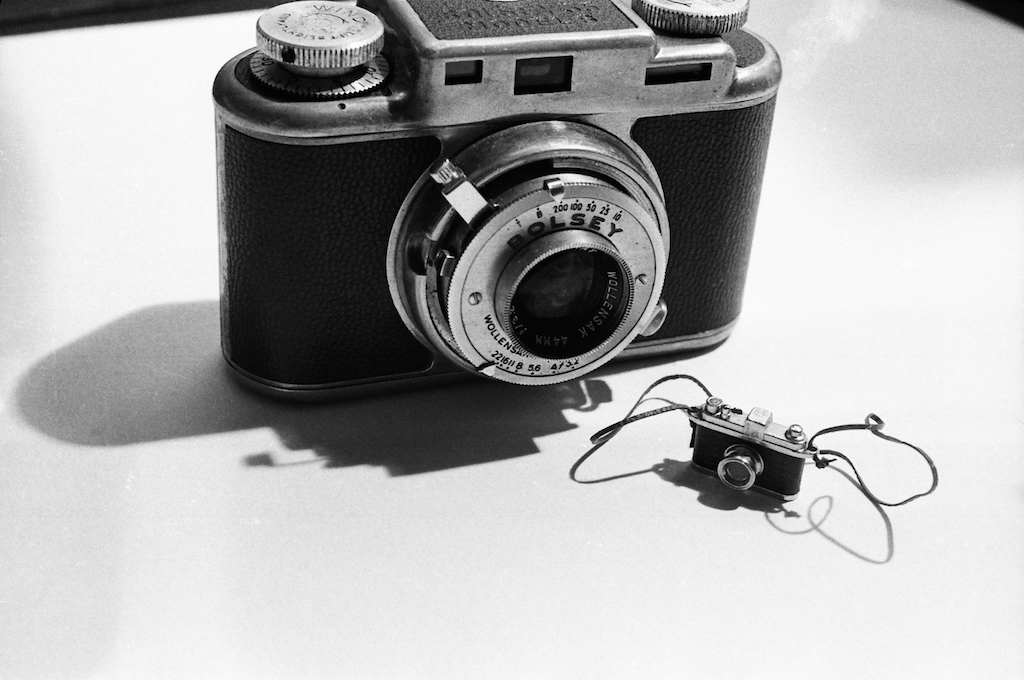

Laurie Simmons, Big Camera/Little Camera, 1976, gelatin silver print.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SALON 94

Walking houses, dolls, and models with painted-on eyes are some of the many subjects featured in the work of Laurie Simmons, who, for the past four decades, has been creating photographs, sculptures, and films that deal with the objectification of women. With a Simmons survey currently on view at the Modern Art Museum Fort Worth in Texas, we’ve collected ARTnews’s coverage of the artist over the years. Included are early reviews of her New York shows, as well as Simmons’s own words on what movies mean to her, from a larger feature by Paul Gardner about artists and film. —Alex Greenberger

“New York Reviews: Laurie Simmons at International with Monument”

By Eleanor Heartney

February 1985

The little plastic ladies are at it again. This time they have ventured out of their tidy color-coordinated ranch houses into the wider world, but the expansion of their horizons hasn’t expanded their minds. Once again Simmons’ focus is on the depersonalization of the modern homemaker. Here, instead of posing as decorative accessories to the suburban dream house, these ’50s-style dolls with their rigid gestures and laminated hairdos are usually arranged in front of projections of the great monuments of human civilization—the pyramids, the Great Wall of China, the Eiffel Tower. . . .

Unlike other aficionados of the staged photograph, such as Sandy Skoglund and Nic Nicosia, who manipulate the photographic image to suggest the fantastic or the surreal, Simmons offers images notable for their utter banality. She employs plastic figures and prephotographed settings to point to the impossibility of unprogrammed activity even during those suspensions from real life that constitute the modern vacation.

“Reviews: Laurie Simmons at Metro Pictures, New York”

By Richard B. Woodward

May 1988

From her small Cibachrome prints of figurines in dollhouses to her poster-size shots of inanimate human bodies afloat in swimming pools, Laurie Simmons has used the exaggerated difference in scale and range of movement between dolls and people for comic pathos and subversion. In 1986 she photographed ventriloquists and their dummies against projected backdrops. In this show, the people vanished and the dummies took center stage.

On one wall Simmons showed five images of “talking” objects—a gardening glove, handkerchief, purse, ukelele, stick on which a mouth and eyes had been fixed—highlighted and set against a domestic backdrop of kitchen curtains. On the opposite wall six portraits of dummies—as dignified and varied as a group of aging actors in summer stock—sat and presented themselves. The objects might have been but weren’t necessarily matched to the dummies, each of which has a distinct mien. “English Lady” has a prissy hauteur; “The Frenchman” is a bored sophisticate; “Suzie Swine” is a drunken slut; and “Young Man” has the bland bonhomie of a talk-show host. As she plays with their characters, and with our readiness to type them and create a narrative, Simmons also critiques the conventions of portrait photography and the collaboration of artist, subject, and audience in assigning meaning.

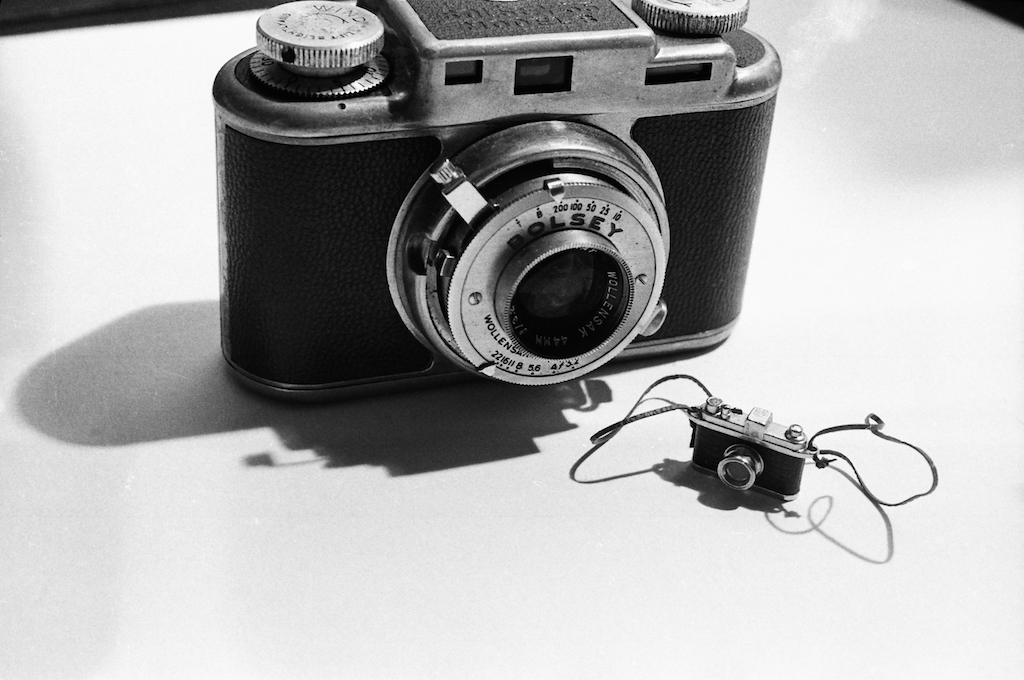

Laurie Simmons, Woman Opening Refrigerator/Milk to the Right, 1979, Cibachrome.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SALON 94

“Reviews: Laurie Simmons at Metro Pictures, New York”

By Elizabeth Hayt-Atkins

March 1990

Laurie Simmons’ latest photographs are tongue-in-cheek critiques of media stereotypes of women. The artist employs an advertising technique of anthropomorphizing inanimate objects by fusing them to pairs of perfect “Betty Grable” legs in order to symbolize cultural abstractions of femininity. Housebound, sweet-natured, and eternally youthful, these are the emblems of the women Simmons creates. The artist’s new work is thematically linked to Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits, but Simmons is more obvious in her feminist attack on conventions of female behavior. Without having to struggle to pin down her intention, the viewer can delight in the weirdness, wittiness, and glamour of her art. . . .

Unlike Simmons’ previous morbid, though equally irksome photographs of ventriloquist dummies, her new pictures are as much fun as the California raisins TV commercials. But they have the punch of a one-line joke.

“Reviews: Laurie Simmons at Metro Pictures, New York”

By Nicholas Jenkins

January 1992

There is a daylight, argumentative side to Laurie Simmons’s work. And there is a dark, metaphor-making side that dredges up memorable night-world images of anxiety and wavering desire. Her latest show was so good because the idiom and illogic of dreams overwhelmed her straightforward, preachy language.

Simmons’ best object-and-dolls’-legs hybrids sprang from the classic line of Surrealist images of sexual exploitation, most explicitly Kurt Seligmann’s Ultra-Furniture and Hans Bellmer’s splayed “Dolls” series. But whereas those earlier artists explored the cold depths of the male unconscious, Simmons draws us into the labyrinths of the female mind and body.

Laurie Simmons, The Love Doll/Day 23 (Kitchen), 2010, Fuji Matte print.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SALON 94

“Lights, Camera, Action! When Artists Go to the Movies: Laurie Simmons”

By Paul Gardner

December 1994

Movies are like songs connected to a certain time, period or place. The first that had an impact on me as an artist were on TV’s “Million Dollar Movie.” My sisters and I liked the ones we called “the water movies”: Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944), where the water is relentless; Leave Her to Heaven (1945), where Gene Tierney, in a jealous rage, lets her husband’s brother drown; and Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid (1948), where William Powell catches a mermaid, played by Ann Blyth, on a fishing trip. The water scenes were beautiful. Ann Blyth was like a woman in a goldfish bowl.

I thought about this film when I made my underwater photographs of people in 1980. I photographed people and dolls underwater and did a frogman series. I recalled the feeling these movies evoked. I was responding to the childhood memories.

And, of course, there’s Portrait of Jennie (1948). Joseph Corten portrayed a painter visited by a little girl from another time. He falls in love with her but can’t save her from a tidal wave because she’s already dead! It’s black and white. The final storm, however, is tinted green, and the final shot is in color.

I still feel that seeing these last images is shocking, like turning on the lights and opening your eyes.

“Reviews: Laurie Simmons at Sperone Westwater, New York”

By Barbara A. MacAdam

June 2004

In Laurie Simmons’s newest exploration of interiors, “The Instant Decorator,” this intrepid investigator of the psychology of home and memory took as her inspiration a 1976 decorating book that offers do-it-yourselfers the wherewithal to reimagine their lives. The book provides transparent paper and line drawings of rooms onto which people can apply samples of fabric and wallpaper.

Slyly, wittily, and bleakly playing on this concept, Simmons designed her own variations on rooms—by means of collage, painting, drawing, and photography—and added a cast of characters, cut out of fashion magazines, clothing catalogues, sex comics, and other random sources. Sometimes she included herself. She then photographed the disparate elements, creating an illusion of seamlessness and permanence.

But nothing is quite right—the characters don’t relate to one another or their surroundings; the patterns and furniture are often the wrong scale—and we feel anxiety as we sense the disjunction between perception and reality.

“Reviews: Laurie Simmons at Salon 94, New York”

By Hilarie M. Sheets

March 2006

[In] her first film, The Music of Regret (2005–6), it seems a natural leap for these characters to start dancing and singing their hearts out about the roles they must shoulder. Two acts of the film were shown here, alongside a 7-by-20-foot photograph from 1991 of Simmons’s “walking objects” taking a curtain call.

In the first of the two acts, “The Audition,” the encumbered legs are instructed by a director’s off-camera to parade one by one onstage to perform and be judged. The handgun seduces with a tango; the house spins under the weight of her domesticity; the book crawls along the floor in a strenuous modern dance. Once the beautiful birthday cake with her ballet legs comes out, the part is cast—before the pocket watch, peeking nervously from the wings, even has an opportunity to audition. Crestfallen, she performs a virtuoso dance on a dark stage to what might have been. Funny and sad, if not exactly subtle, the vignette rings true as a parable about women being through the paces of their lives.

Laurie Simmons, How We See/Ajak (Violet), 2015 pigment print.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SALON 94

“Laurie Simmons: Eyes Wide Shut”

By Andrew Russeth

March 2015

In recent years Simmons has been moving increasingly toward art made with human-scale surrogates, which has caused her work to grow more uncanny, more unsettling. In 2009 she began making work with a high-tech Japanese love doll, which in turn led her to kigurumi. She’s also shot disturbing-looking male medical dolls, whose eyes stay closed. “This kind of realism, this kind of picture, where you really don’t know what’s wrong, or what I’ve done to alter or invade the space, that’s kind of new for me, ” Simmons said proudly.

“The idea that she can see them, but they can’t see her—this funny idea of the creepy photographer—is super interesting to me,” said curator Kelly Taxter, who’s organizing [Simmons’s] Jewish Museum show. She likened Simmons’s new work to a kind of post-Pictures practice, one that is attuned to the ways in which users construct and disseminate their own images on sites like Twitter and Instagram, where Simmons has a strong following (about 67,100 followers as of press time).

As it happens, Richard Prince took a screenshot of one of the “How We See” images on Simmons’s Instagram account and printed it as his own artwork for a show at Gagosian in New York. Simmons went to see it and was not happy.

That was surprising to me; Prince’s move felt like no more than the logical, perhaps slightly bland, next step for a Pictures artist navigating the digital present. “I was pissed off because my work had been stolen by him,” Simmons told me. “And then I thought, ‘Wait a minute. I’ve spent my life stealing.’ I’ll call it ‘borrowing.’ I’ve spent my life borrowing. It was really this cascade of emotions.” In the end, “I think I was sufficiently pissed off that I had to get back into the studio,” she said. “Ultimately, it had a great effect on me.”

[ad_2]

Source link