[ad_1]

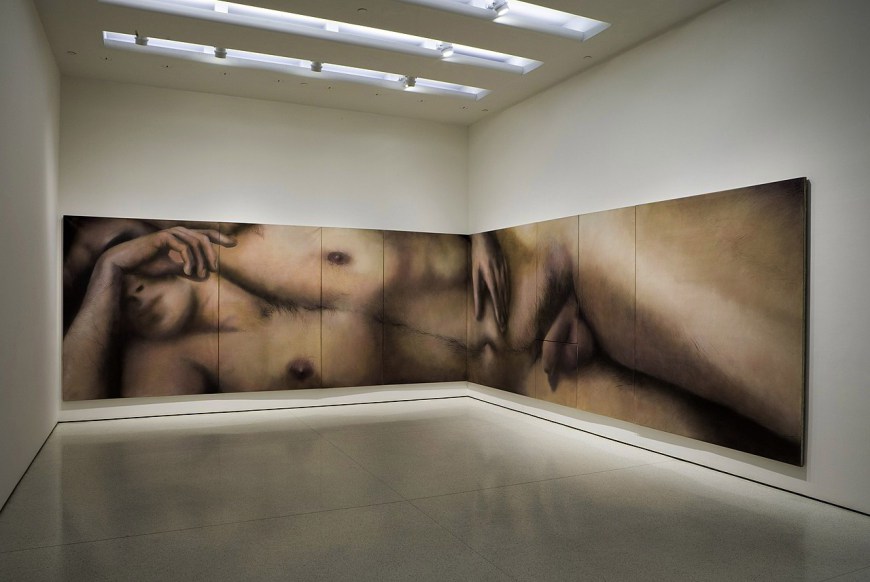

Harold Stevenson, The New Adam, 1962.

COURTESY THE GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

Artist Harold Stevenson, who had a gargantuan nude rejected from a landmark show at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, appeared in the films of Andy Warhol, once hung a piece from the Eiffel Tower, and produced potently erotic paintings of the male body, died on Sunday in his hometown of Idabel, Oklahoma, at the age of 89. Dian Jordan, a sociologist who has been interviewing Stevenson for a biography about him, confirmed his death, and said that he had recently been ill.

Stevenson played a role in an astounding number of the key moments in postwar vanguard culture, but he is, without question, best known for The New Adam (1962), an audacious painting of a nude young man measuring 8 feet tall and nearly 40 feet long that was meant to stretch across three walls. The critic and curator Lawrence Alloway had seen a preparatory work for The New Adam, and he planned to put the final product in his 1963 exhibition “Six Painters and the Object” at Guggenheim, alongside works by fast-rising Pop artists like Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, and Warhol, but he balked when he was presented with photographs of the painting.

Writing to Stevenson’s Paris dealer, Iris Clert, Alloway said that he had chosen not to show the sprawling painting “so as not to cause an imbalance in the exhibition,” explaining that “the whole weight of public attention would be drawn towards The New Adam.” Emphasizing that his decision should not be taken as an insult, he said, “I suppose it is a tribute to the painting that I feel I cannot show it.” A Robert Rauschenberg work took the place of The New Adam.

Harold Stevenson installing his work at the Eiffel Tower.

Stevenson later said that Alloway “went into shock” when he saw the nude, for which the actor Sal Mineo (of Rebel Without a Cause fame) had served as a model. “I had never heard of him, but he was very good looking and beautifully proportioned,” the artist said of Mineo. The New York dealer Mitchell Algus recalled Stevenson saying that the figure’s head, which is partially covered by his arm, belongs to the artist’s then-partner, Timothy Willoughby, a member of the Astor family, who was lost at sea in 1963.

When Algus went looking for The New Adam around 1990, he found the painting rolled up in the basement of a Long Island City townhouse where Stevenson lived with his longtime partner Lloyd Tugwell, who died in 2005.

Algus inaugurated his gallery with a display of The New Adam, and went on to do five more solo shows of Stevenson’s paintings—predominantly intense close-ups of the male body, often in soft tones, that exuded an intimate but fantastical eroticism. He noted that, when Stevenson was showing his work in the 1960s and ’70s with dealers like Clert and Richard L. Feigen, reviews of his shows were frequently negative and marked by homophobia. “This art is the expression of a pervading, painful and limp ennui, but so skillful that it is not quite a cliché,” one ARTnews item from 1963 reads.

But times and opinion changed. In 2005, the Guggenheim Museum acquired The New Adam, under the aegis of curator Robert Rosenblum, who told the New York Times, “It’s a seminal work. It marks a crucial development not only in the exposure of the full-frontal male nude but also in the billboard-scale wraparound installation, like Rosenquist’s F-111 in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection.”

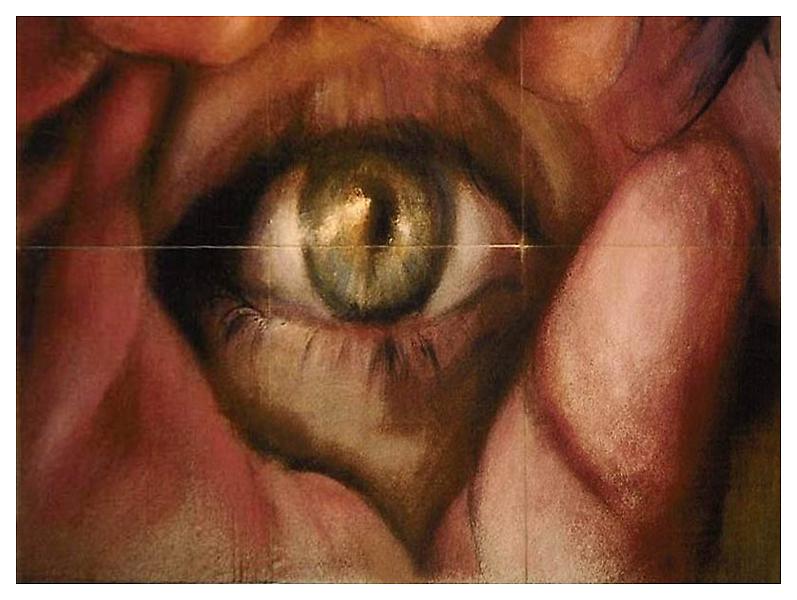

Harold Stevenson, The Eye of Lightning Billy, 1962.

COURTESY MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY

Harold Stevenson was born on March 11, 1929, in Idabel, Oklahoma, a small town near the state’s borders with Arkansas and Texas. Before he even became a teenager, he began teaching himself to paint, and said that by the time he was 10, he had a little studio in a building downtown where he would do people’s portraits. “I painted all the people who came there, and that was everybody,” he told Steve Sherman in 2013.

He attended the University of Oklahoma, and, on the advice of architect Bruce Goff, departed for the Art Students League in New York in 1949, where he quickly fell into the art scene. He showed that same year at the Hugo Gallery, run by the dealer Alexander Iolas, and quickly became friends with the writer and artist Charles Henri Ford and the fashion designer Charles James, for whom he worked for a time, among others.

That same year Stevenson met Warhol, who had arrived in the city from Pittsburgh earlier in the year. They would quickly become friends. Stevenson said that he introduced Warhol to David Mann, who was then running a space called the Bodley Gallery, where the future Pop superstar would have his first solo show. Later, Stevenson appeared in some of Warhol’s films, including Kiss (1963), for which he locked lips with the artist Marisol, and Heat (1972).

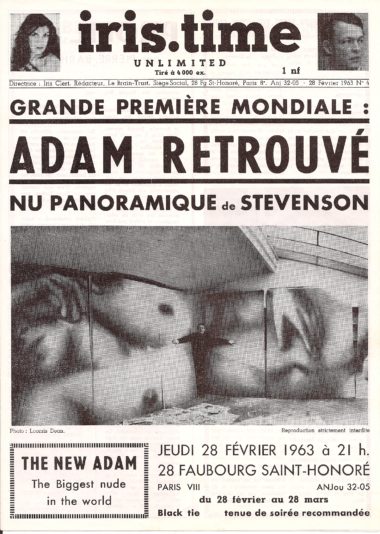

A pamphlet advertising Stevenson’s 1963 show at Iris Clert in Paris.

In 1959, Stevenson decamped to Paris, where he lived for many years. He once told Algus that Marcel Duchamp suggested he go there because, if he remained in New York, he would become an Abstract Expressionist. But he was resolutely itinerant throughout his life, regularly traveling between the French capital, New York, Key West (beginning in the 1980s), and his hometown. “I always came back to Idabel,” he said in a 2006 interview with Tawsha Brinkley Davenport in the McCurtain Daily Gazette. “I was one of the first jet-setters. I always moved around. I didn’t think anything about it. If I felt I needed to be in Italy, I went to Italy.”

Clert showed The New Adam in Paris in 1963, declaring it the “biggest nude in the world” in a promotional pamphlet that also reproduced Alloway’s letter declining to show the work at the Guggenheim. Later that year, she helped arrange for Stevenson to display another gigantic painting—this one 48 feet tall, of the famed Spanish bullfighter El Cordobés (Manuel Benítez Pérez)—on the Eiffel Tower.

When Davenport asked Stevenson about his artistic influences, the artist mentioned Leonardo, but proposed that, because he taught himself art at such a young age, he had resisted the sway of others. Over the years, his work mixed in various quantities an exuberant Mannerism, a bodily focused Surrealism, and a passion for antiquity. In Raft of Medusa (Breakfast of Mars), in which rose-colored lips consume the inhabitants of that same-named Géricault scene, or The Eye of Lightning Billy, a huge eyeball encircled by a hand that appeared in the storied 1962 Sidney Janis gallery show “The New Realists.”

“The art and career of Harold Stevenson—not unlike his own life—has defied convention in virtually every way imaginable,” the artist and gallery director Ron Clark, who was a lifelong friend, has written. His work has also proved intriguingly prescient, and one can see it pointing the way to numerous figurative-minded artists working today with the psyche, sexuality, and the absurd, from Jana Euler to Jamian Juliano-Villani.

“He was just the best,” Algus said. “He would instantly make friends with everybody.” Recalling running into the Salvador Dalí at one point, Stevenson said, “He was an eccentric, but then I am an eccentric, an Idabel eccentric. My grandfather and father were eccentrics. I always thought it was one of the most natural things in the world to be an eccentric.”

While the mainstream embrace of his work has been slow, a small handful of museums have acquired his work over the years—the Guggenheim, most notably, in 2005, the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, in 2008, and the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, which in 1968 accepted as a gift a small two-panel painting of a man’s arm posed alongside his naked body. None of these works is currently on view to the public. There is a lot of catching up to do.

Speaking about his early years in Paris with Adrian Dannatt in a 2002 interview in The Art Newspaper, Stevenson recalled, “One morning my adorable dealer Iris Clert phoned me at my apartment in Paris and said, ‘Oh Harold, I’ve just had the most brilliant idea. You have lived too long. You have lived too long, if you were dead I could make you famous and rich overnight.’ I replied but Iris I’m hardly 30 years old! She pondered on this and then said, ‘In which case Harold you will have to out-live the bastards’—and so I have!”

[ad_2]

Source link