[ad_1]

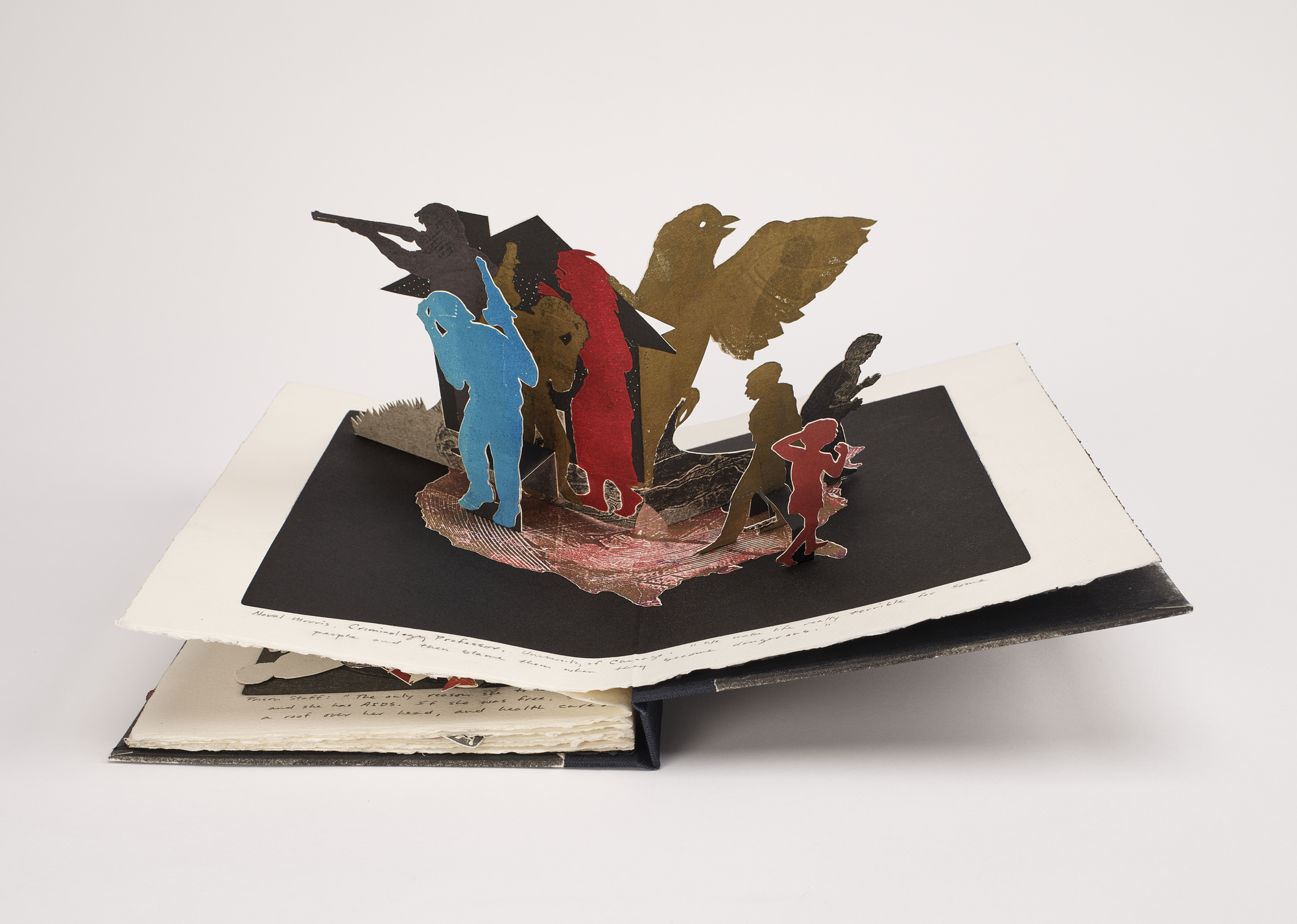

Beth Thielen, Why the Revolving Door: The Neighborhood, the Prisons, 1992, monoprint, pencil.

COURTESY LOS ANGELES, GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE/© 1992 BETH THIELEN

In 1985, the year that the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles acquired collector Jean Brown’s archive of avant-garde artists’ books, which includes (to name just one piquant example) a Dieter Roth work involving a mysterious substance that might be cheese, an exhibition of such unusual works was almost unimaginable. In a post on the Getty’s blog, Marcia Reed, the chief curator of the GRI, recalled that, when she was unpacking Brown’s unorthodox, irreverent books that year, “our director just happened to swing by. He took one look at the boxes, books, and objects, and said, ‘What is this [#%]!’ ” And this was not a man known for swearing.

“In the late eighties and nineties, artists’ books seemed to get no respect,” Reed continued. “They were dismissed as secondary, not really art. For libraries, they were quite problematic as books, although art libraries collected and championed them.”

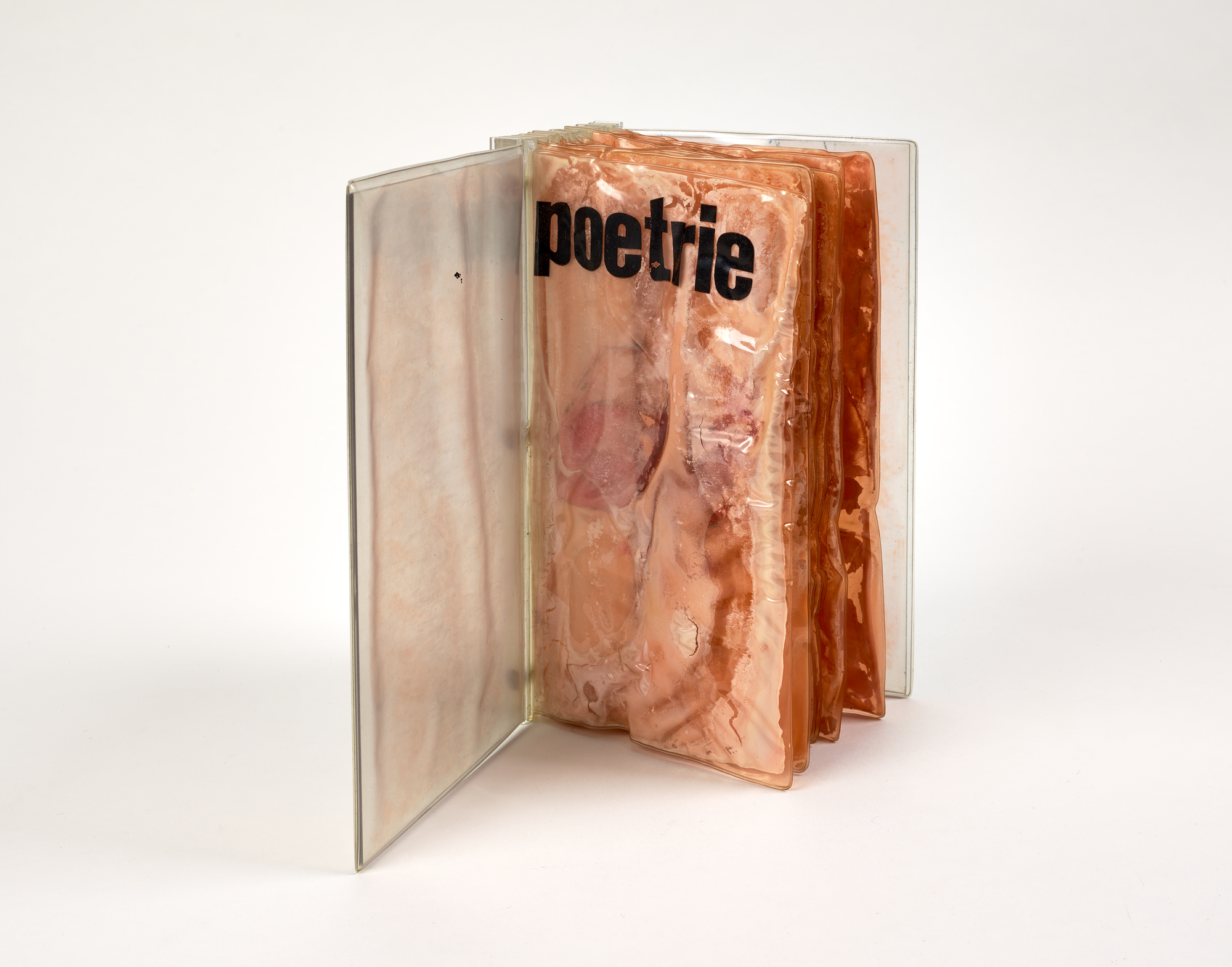

Dieter Roth, Poetrie, 1967, clear plastic, plexiglas, metal screws, substance (possibly cheese).

COURTESY LOS ANGELES, GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE AND HAUSER & WIRTH/© DIETER ROTH ESTATE

But since then, Reed has played an integral role in developing and expanding the GRI’s collection of artists’ books. And, in an exhibition at the Institute titled “Artists and Their Books / Books and Their Artists,” she and Glenn Phillips, its head of modern and contemporary collections, are showcasing some 40 outlandish, intricate, and engrossing works, from a transparent, silk-screened compendium of geometric puzzles by Tauba Auerbach, to a delicate paper egg that resembles some sort of sorcerous object by Barbara Fahrner, to 27 looseleaf pages detailing Chris Burden’s run-ins with the coyotes of Topanga Canyon, as well as pieces by Jennifer A. González, Sol Lewitt, Ed Ruscha, William Wegman, and many others.

“The idea of the exhibition was not to show the artist book that everybody knows,” Reed told me in a phone interview, “but show artists like Andrea Bowers who makes books, archives, books as installations and memorials, and how they make things work also for social and political statements.”

Unexpected forms abound. Cecilia Vicuña’s hanging Chanccanni Quipu, made of un-spun fleece, which references the ancient Incan tradition of quipu, a system used for storing information through knots in fabric. Figurative silhouettes—confined within prison walls or situated in more abstracted environments—populate scenes of abjection in Beth Thielen’s haunting pop-up books, which subvert their conventionally whimsical forms in jarring ways. And Your House by Olafur Eliasson is comprised of 454 laser-cut pages that present an architectural outline of the artist’s Copenhagen home in assiduous detail.

The exhibition, which runs through October 28, offers new points of entry into the imaginations of contemporary artists, especially some who are not widely known for making books. Oftentimes—and rather delightfully—it feels as though the artists’ own idiosyncrasies are projected onto their creations. Dave Eggers’s shower curtain, for example, features a written soliloquy from the perspective of the object itself, and Russell Maret’s bright geometric shapes commingle enthusiastically near his accentuated letterforms, which convey mathematical principles—in effect, the artist has concocted his own artful geometry.

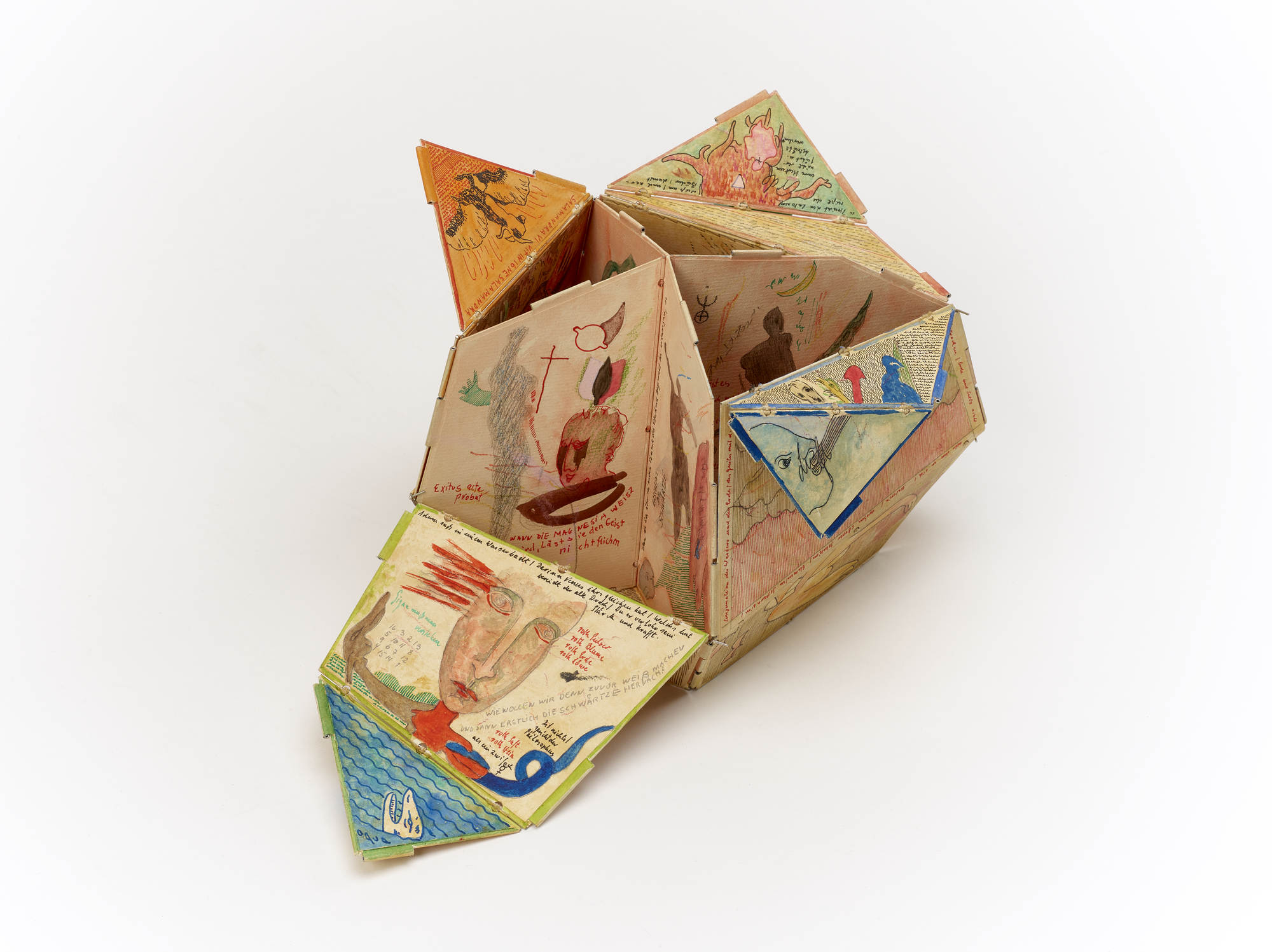

Barbara Fahrner and Daniel E. Kelm, The Philospher’s Stone, 1992, museum board, paper, stainless steel wires, tubing, colored ink, pencil, watercolor.

COURTESY LOS ANGELES, GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE/© BARBARA FAHRNER AND DANIEL E. KELM

All of the exhibition’s aesthetic intrigue and tactile appeal notwithstanding, Reed hopes that visitors will also consider the written messages within many the artworks. Deciphering details of many of the works on view requires a bit of persistence and commitment, and peering through and around glass displays to uncover such secrets can be painstaking work. But there’s an intimacy that accompanies engagement with these talismanic pieces.

“Marcia Reed likes to read, and so I’m incredibly involved with books and also the text in the book and the way that text can be read differently and how important that is,” Reed said. “So in the exhibition, one of my goals was not to just show the materiality or the paper and design, but really try to focus on the words and why that combination was very important.”

With the Getty Research Institute’s stacks in sight of the galleries, the exhibition underscores the fluidity and flexibility that has always been central to bookmaking, and insists on the futility of classifying these works, which, occupying interstitial spaces, function as sites of mystery, invention, and possibility.

[ad_2]

Source link