[ad_1]

Ming Smith, Casablanca, Harlem, NY, ca. 1983.

COURTESY STEVEN KASHER GALLERY, NEW YORK

After stops at Tate Modern in London and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, the critically acclaimed, and hotly anticipated, exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” has just opened at the Brooklyn Museum.

Collecting pieces from 1963 through 1983 by more than 60 artists, the show focuses on a period when black people were fighting for legitimacy in the eyes of the law and of their fellow men and women in every area of society. Presenting the work of artists in the Black Arts Movement as well as collectives like Kamoinge, AfriCOBRA, and the Spiral Group, the exhibition presents a diverse array of approaches, from figures who highlighted the plight of black people and advocated for radical visibility and equality to those who were less inclined to engage in active commentary but still made statements by asserting their visions in a world set to snuff them out. With historical material that remains under-known in the United States, “Soul of a Nation” asks nothing less than this: What can art do in the world?

In the lead-up to the opening, I spoke with four artists in “Soul of a Nation”—Ming Smith, Betye Saar, William T. Williams, and Senga Nengudi—about their work, the ambitious exhibition, and where we go from here.

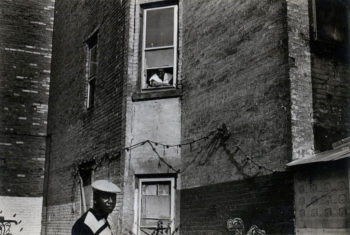

Ming Smith, When You See Me Comin’ Raise Your Window High, New York, NY, 1972.

COURTESY STEVEN KASHER GALLERY, NEW YORK

MING SMITH

As a member Kamoinge, a collective of black photographers in New York in the 1960s, Ming Smith focused on black-and-white street photography, a format that means you have to “catch a moment that would never ever return again, and do it justice,” she said, when I met her at her Harlem apartment. We sat and talked in her balmy living room (the A/C was acting up on this day), surrounded by prints of various sizes, including some of Alice Coltrane, who’s the subject of a new project by Smith. Her assistant was sorting through digitized photographs (color as well as black-and-white), in preparation for an upcoming show. Ming, who was the first black woman to have her work enter the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, said that she has always considered her photography the key to her vitality, a protective disguise to weather any uncomfortable situations, and a gateway into the multidimensionality that exists in people. Her works in “Soul of a Nation” include Hart-Leroy Bibbs, Circular Breathing (1980), When You See Me Comin’, Raise Your Window, High, New York City, in New York (1972), and Casablanca, Harlem, NY (1983).

ARTnews: Do you remember when you took the photos that are featured in the show? How was it that you found yourself in these locations?

Ming Smith: I was living in the Village and I would just photograph Harlem. I was introduced to photography as an art form through Kamoinge, and most of [its members] lived in Harlem. They were like pioneers in photography, and they started this group to have some control over their own image.

What made joining that collective particularly appealing to you? Was it the idea of being highlighted as a black artist?

Oh no, there was no highlighting. There were no platforms. There were no talks. If there were, no one knew about them. Maybe in the white world. As a photographer, as a woman photographer, there was nothing. Back then, there was nothing like that, no one who could book you here and there. Honestly, I was drawn to it because it was the first time I was introduced to photography as an art form. Lou Draper invited me. I had a two and a quarter; someone gave me their camera because I couldn’t afford a camera then.

Ming Smith, Hart-Leroy Bibbs Circular Breathing, 1980.

COURTESY STEVEN KASHER GALLERY, NEW YORK

When you were out there taking photos, did you have in mind any political angle that you wanted to take using your photography?

When I came to Harlem, what was missing for me a lot was the love in photographs of us—the dignity of the race, things like that. I didn’t see that in images. Sometimes, now, I still don’t see it, but the landscape has completely changed. But back then, many times I would just see people impoverished. I wanted to show the grace, the love, and—how do you say?–the surviving. You know, still surviving. Dignity. My sister—she passed a long time ago—she said, when I was still in college or right after that, she said to me, “You look for truth.”

“Soul of a Nation” is highlighting works from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. To you, what does it mean for these works to be shown right now?

The main thing—celebrate our struggle. Throughout all the chaos, this is survival. These are the people who did the work—it was always for a higher purpose.

Betye Saar, Mti, 1973.

ROBERT WEDEMEYER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ROBERTS PROJECTS, LOS ANGELES

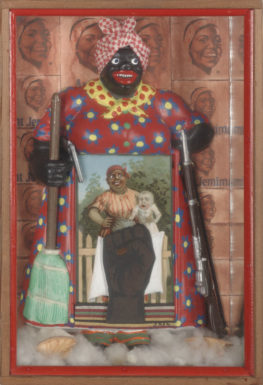

BETYE SAAR

Betye Saar’s work, which often combines sculpture and collage, aims to turn negative images of black people on their head. Using materials like wood, cotton, paint, and fabric, Saar makes work that she divides into three categories: “ancestral art,” or art influenced by African sculptures, altars, relics, and other mystical figures; “derogatory images,” like any references to “mammies, darkies, or other ways black people have been depicted,” as she put it in a telephone interview from early August; and finally “personal history,” using mementos like family photographs (her own or others) as material to illustrate the post-slavery era, in which former slaves tried to piece together a livelihood—and a place—in a country that had long sought to suppress it. She never expected that her artwork would play an advocacy role when she made it, she said. She wanted to be involved with the struggles of black people and expressed her personal grievances through her art. Works in “Soul of a Nation”: Mti (1973), The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), House of the Head (1971), Eshu (The Trickster), 1971, and many others.

ARTnews: What does it mean to have your work presented in the current political climate?

Betye Saar: Well, I’m pretty matter of fact: I just make the work. How I’m selected to the show really depends on the mentality and the opinion of the curator. I make the art about things that I feel strongly about and most of those things, during the period of the ’60s and ’70s, were derogatory images. I felt that black people, all they ever had to look at were derogatory images, like the Aunt Jemima or the Uncle Tom or a person being lynched or things like that. I thought, How could I, as an artist, take those images and turn them about so they could make something else? In the case of The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972): take a woman who was a victim and make her a warrior.

What was it like to be a black woman artist during the time you created the works presented in “Soul of a Nation”? What was it like to make your work during that time?

What would I have to compare it to? I just make my work, just like most artists. Most black artists did that. Some artists classified themselves as black artists and some of them just classified themselves as artists who happen to be black. That’s still true today. I consider myself an artist. Of course, I’m a woman; I’m a woman artist. I’m a mature, older artist. I’m black. The artists make the work and sometimes they deal with big issues.

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972.

MIXED MEDIA ASSEMBLAGE, 11.75″ x 8″ x 2.75″, COLLECTION OF BERKELEY ART MUSEUM AND PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA; PURCHASED WITH THE AID OF FUNDS FROM THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS (SELECTED BY THE COMMITTEE FOR THE ACQUISITION OF AFRO-AMERICAN ART), COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ROBERTS PROJECTS, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA; PHOTO BENJAMIN BLACKWELL

Do you believe there is such a thing as the black aesthetic?

I believe it exists because some people really believe it. But it’s not my personal belief. It’s just like saying, “Oh, that’s black jazz!” Not all jazz is black and not all jazz musicians are black. It’s just like anything that’s creative, it’s going to run the gamut. People are going to try to pigeonhole it in one place or another. I probably have a sensitivity that is black, just from my culture, from the way I was raised. People try to pinpoint and make you fit into a slot and you don’t always fit in that.

What feels important about exhibitions showcasing black artists?

A lot of people have not seen it, still do not know that there are black artists or that black artists have shows. The more that’s out there—even women shows, Asian shows, Hispanic shows—the more that people are educated, the better it is. It can even be tighter—black women artists, young women and older women, people who use certain imagery—the tighter it is, the more people will look for things that they’ve never seen before.

Do you think there is a particular audience that your work speaks to?

I don’t know. It depends on who goes to the museum. But you know, once I make the work and put it out there, I’ve moved onto something else. I’m not even thinking about that anymore.

William T. Williams, Trane, 1969.

©WILLIAM T. WILLIAMS/COURTESY MICHAEL ROSENFELD GALLERY LLC, NEW YORK/THE STUDIO MUSEUM IN HARLEM, GIFT OF CHARLES COWLES, NEW YORK

WILLIAM T. WILLIAMS

Williams has been painting for more than 50 years. Best known for his early hard-edged abstractions—which he’s termed “full-spectrum” paintings—in which a wild array of colors interlock and overlap, playing with dimension and geographic form, he later created what he calls “shimmer paintings,” which emphasize the texture of the brush on canvas and shimmer under light. I met Williams in a small side room at his gallery in Chelsea, Michael Rosenfeld, in which three of his pieces were hanging for the interview. Surrounded by his work—two of his angular early pieces and a “shimmer” painting—Williams, expounded with soft-spoken ease on his evolution as an artist and the importance of the engagement between artwork and viewer. Works in “Soul of a Nation”: Trane (1969) and Nu Nile (1973).

ARTnews: What was it was like crafting these pieces in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and what it’s like for them to be in a show in the current political climate?

William T. Williams: The current political climate is very similar to the climate during which they were constructed and painted. It was a time when our country was looking at itself, trying to make decisions about its destiny. Trying to make decisions about correcting past mistakes. And there was a national dialogue at that point, where the artist entered that as well. So, I see the two eras as being very, very similar.

From my standpoint, in terms of trying to make these paintings, my intent was to make the best painting that I possibly could. I was developing a personal touch, literally in terms of how the brush engaged the surface of the canvas. And my thoughts were very much [that] the history of painting was the history of the brush—that I had to find a way of rethinking that. And thus, the shimmering came out of that.

There was also the kind of physical engagement that you had with the paintings. As you look at them and as you move past them, there’s the sense of the surface being alive and moving and kind of interacting with you. So, all of those phenomena for me were very much indicative of what was going on around me—wanting to engage the viewer in a different way, wanting to engage the viewer about a different dialogue about identity, about abstraction and about painting in terms of the latter part of the 20th century.

What was it that sparked the transition between making the “full-spectrum” paintings and the “shimmer” paintings?

It was a reaction to an article, a criticism about the paintings. The indication was that artists of color did bright-color paintings, which was a, you know, kind of enormous stereotypical thing. I took it as a challenge, though. And I took it as a challenge to myself to begin to make a tonal series of paintings, and to make—isolate down to two colors and see how many tonal variations I can get out [of] two colors. It had to do with me finding a device that I could grow as a painter. And letting go of the color, which was the thing that people were kind of hanging my importance upon.

What is your relationship with the other artists in the show?

A lot of the artists that are in the show, I’ve known some of them for 50 years. There’s a shared history, there’s a shared sense of accomplishment, shared sense of disappointments, and all that stuff goes into just creating who you are as an artist.

William T. Williams (b.1942) Nu Nile (Shimmer Series), 1973.

©WILLIAM T. WILLIAMS/COURTESY MICHAEL ROSENFELD GALLERY LLC, NEW YORK

I guess that’s the name of the game, in terms of curating.

Well the show is organized in terms of both geography—of West Coast, East Coast, Middle America—it’s also organized in terms of stylistic things that occurred, and then pairing in terms of artists that were interacting with each other. There’s an enormous diversity within the artists themselves. And I think what the show does, and what I like about the show, is it suggests there are 64 different artists with 64 different solutions to what they thought art was, at a given point.

Do you mean 64 different solutions to what they thought art was in general, or what role art played in social justice, for instance?

No, no, I mean, in what they thought that art was. An artist goes in the studio, he or she makes a commitment to that act of the creative process. For me, painting is not about literature. Painting is very much about your experience of an object and the longer you can get a viewer to have that experience, the better the viewer is. There’s a very large range of artists over the years that I knew. Some [were] very socially, politically conscious in their work; others were not that interested in that.

What I always remember is, it’s one thing in terms of looking at their art, and that experience; it’s a very different thing in terms of your engagement with them as a human being, and in terms of the friendship and to have the shared idea of being an artist. You know, being on the bandstand, a group is playing. I don’t think they’re asking each other about their politics. They’re trying to make that music as effective and as powerful [as possible], and to affect the community spirit. Whether you’re Faith Ringgold or you’re Jack Whitten, art is about the affirmation of life. In the face of all the adversity that the artists in this exhibition faced, they kept working, because they believed in the power of art to change lives and to affect the future.

In the foreword to the show’s catalogue, Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation, says a lot about what he envisions the show to be in terms of its possible effect on the people who come and view it—he says it could cause people to “interrogate the world as it is and imagine how it could be.” What do you say to that?

Art has been really important to me, given where I started from—which is the rural South. It’s very hard sometimes for people to fathom that I grew up in a house where there was no running water, there was no indoor plumbing. This is back in the ’40s. There were no paved roads. Certainly no electric. A really different experience than now. I think art has to the power to change people. And when I say art, I’m including all the arts—music, painting, dance, whatever it may be. It has a power to change societies. Once you embrace the arts, once you embrace culture, there’s a glue that holds something together.

If there’s a message to young artists, I will give them the message that [Romare] Bearden gave me. That art-making is an old man’s game. And it takes time to kind of isolate your temperament, your sensibilities, and focus your energy toward that. That in the very beginning, everybody has talent, but talent is really not the issue. It’s how you can effectively put that talent to work to best meet this challenge of affirming life.

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. XI , 1977/2004.

COURTESY THE ARTIST, THOMAS ERBEN GALLERY, NEW YORK, AND LÉVY GORVY, NEW YORK and LONDON

SENGA NENGUDI

Senga Nengudi has made her name with nylon, a pliable and expandable material that has symbolized the body and mind in different states. In some cases, her abstract sculptures, which at times also involve rubber, sand, and cardboard, are exhibited as a static installation; in others, she or other artists activate a piece by physically engaging with it, like with her R.S.V.P. XI, which was presented in 1977 at the Just Above Midtown gallery in New York, a haven for black experimental artists. Nengudi spoke from her home in Colorado Springs, Colorado, by phone to discuss the interplay of energy and urgency in her works and the times in which her art exists. Works in “Soul of a Nation”: Untitled (1976), Internal II (1977/2015), and R.S.V.P. XI (1977/2004).

ARTnews: What does it mean to reactivate or reanimate work in a different time and setting than when it was first conceived?

Senga Nengudi: Spaces are different, you know, and that difference in energy brings its own story to the work. Because of the nature of my pieces, there’s a certain level of intimacy. Even the installer has a role in providing energy to each piece.

Will you not be accompanying the “Soul of a Nation” works to the Brooklyn Museum, then?

No. There are people I trust who I send along with the work. Trust is important! Other times, I have made videos of some, as instructions for how a piece should be installed. Most galleries don’t have personnel with that level of expertise. Before agreeing to a show, it’s good to know and trust the curators—amazing curators, they’re really undervalued; everything is in their hands.

What role do shows like “Soul of a Nation” play for you?

They serve [to show the] breadth of history, connecting the dots between then and now, so to speak. It’s the opposite of devaluing. In the ’80s, there was a resurgence of black L.A. artists working together. It was a time that America was dealing with things that were segmented, divisive. Retrospective shows give recognition to different groups of artists and different times—like a reclaiming of space.

Senga Nengudi, Untitled, 1976.

COURTESY COURTESY THE ARTIST, THOMAS ERBEN GALLERY, NEW YORK, AND LÉVY GORVY, NEW YORK AND LONDON

I sense a thread of urgency within “Soul of a Nation.” Can you explain, if any, the urgency associated with your work?

You know, abstraction has a way of hitting on themes with universality. With my work, there was an urgency to express this phenomenal thing that happened to me—an elasticity with my body and with the psyche. Today, there’s an urgency and stress that comes with the things going on in America today. There is this urgent approach to the political, which is so drastic sometimes. Getting to the core of it all, sometimes it’s easier to express with abstractions as opposed to realistic portrayals in art. My work—the inside of you is pretty and ugly at the same. Blood gurgling, bubbles of fat, and all that. It’s like that. Abstraction allows for a third language; what’s happening today—sometimes it’s easier to deal with it performatively and communally.

“Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” runs at the Brooklyn Museum through February 3, 2019, and will open at the Broad in Los Angeles in March.

[ad_2]

Source link