[ad_1]

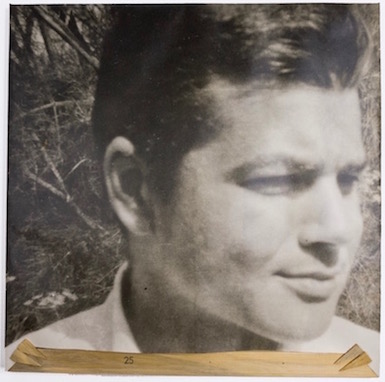

Dale Henry, The Old Bowery.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

Dale Henry was an artist who met with some success in New York in the 1960s and ’70s—notably showing with Alanna Heiss at the Clocktower Gallery and the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center as well as with the dealer John Weber—before leaving the city in disgust and landing in rural Virginia to work in isolation for the rest of his life. When Henry died in 2011, at the age of 80 and more than three decades after having fled what he perceived as New York’s market-minded preoccupations and mislaid artistic attentions, Heiss was notified that his will called for all of his work to be left to her—with the stipulation that it either be given away for free or destroyed completely. That left only museums and sympathetic recipients as prospective caretakers for hundreds of paintings and sculptures whose fate hung in the balance.

Though the posthumous request came as a surprise, Heiss took on the duty, with some reluctance, and proceeded to exhibit Henry’s work, first in a tribute at the Clocktower Gallery in Lower Manhattan in 2013 (in the final exhibition there) and then the next year in a bigger show at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn. Since then, Heiss and curator Beatrice Johnson, the project director for the whole affair, have toiled to find homes for the works—many of them post-minimalist and conceptually inclined paintings made with unorthodox materials—to live on in an endeavor that recently wrapped after years of planning and execution. Among the institutions that have acquired works by Henry as a result are the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Brooklyn Museum, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Birmingham Museum of Art. Individuals who wound up with works as gifts include artists Joan Jonas, Lynn Hershman-Leeson, Robert Wilson, Dustin Yellin, and many more, including an ARTnews writer who was invited to take part in a Henry-related roundtable discussion convened by Heiss in July.

Dale Henry.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

Among talks delivered by a varied cast—MoMA curator Laura Hoptman (who since left the museum to become executive director of the Drawing Center), photographer Todd Eberle, Dennis Oppenheim estate executor Amy Oppenheim, Lawrence Weiner archivist Kirsten Weiner, and yours truly—were spirited additions and rejoinders from an audience that included some of Henry’s old friends and colleagues.

Hoptman spoke of the challenges and oddities surrounding MoMA’s acquisition of a very complicated multi-part work by an artist of little notoriety. Hoptman herself hadn’t been familiar with Henry prior to Heiss’s recent handling of his work, but the notion of adding him to the museum’s collection came about, Hoptman said, after museum trustee Agnes Gund and curator Ann Temkin had seen it and found it to their liking. The work now belonging to MoMA is a sprawling series of wall pieces, dated 1972, made with materials like sand, masking tape, thread, paintbrush bristles, marker, and pencil on supports like waxed paper, linen, acetate sheets, glass, and more—all under the collective title Primer sets of a revealing graphic, personal history of Western Painting using the complete and basic iambus throughout. Eighty pieces, ten each set of eight: Marster Buckt Tho Nitid / Makar Vanisht Oyez Fúnnee.

“What does it mean to acquire a large, space-hungry work by an artist who doesn’t have any name recognition?” Hoptman asked, rhetorically, at the start of her talk. “What does it mean to acquire a work that is challenging to install in the way the artist intended?” she added, mentioning Henry’s meticulous instructions for hanging the work. (This one “came with a handbook,” she said.) Later on, in response to a question about caring for a fragile work that might not go on show anytime soon, Hoptman said of MoMA, “We’re not just showers—we’re preservers, too. Dale Henry will live as long as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and will be treated in the same manner as van Gogh’s Starry Night.”

Dale Henry’s Primer sets of a revealing graphic, personal history of Western Painting…, as seen at Clocktower Gallery in 2013.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

Artist Richard Nonas interjected that what is most significant about Henry, more than any single work in his oeuvre, is how he managed to make a legacy for himself after his death. “I feel like this work exists primarily and to a certain extent only as a conceptual, cooperative piece between you and Dale,” Nonas said, addressing Heiss. “It’s extraordinary—this notion of taking a life’s work and giving it away. For every one of these works, the main importance is that it’s part of that, and to separate it from that is to kill it. Dale knew he was creating a situation in which it was going to be impossible to look at the works without knowing the history of how they got in front of you.”

The gambit proved fruitful, Nonas suggested. “This project changed the meaning of any one of these things, as part of the great giveaway. Nobody who knew him in New York thought that Dale was a great artist—he was a good artist, a strong artist, and a representative of his time, as were 50 or 60 others. What’s really interesting is the way he closed his life up and made it into a single work.”

Heiss had said earlier, not mincing words, “By the way, I didn’t want Dale’s work.” He had proffered such an arrangement with her when she was the director of P.S. 1 (now MoMA PS1), but, as a non-collecting entity, the museum had no way to broker such a deal. But then, despite repeated refusals over the years, came the letter after Henry’s death, asking for either acceptance or doom by the way of flames, and the fate of the work was sealed. “He left instructions with his very articulate and Faulknerian Southern lawyer language to see that this happened in a bonfire,” Heiss said of the less desirable option.

Also up for discussion was a matter of biography that Henry had worked to hide from almost everyone who knew him. As Heiss had previously made known to only a handful of people in the past seven years of working on the project—and chose to divulge publicly for the first time at the event—Henry “carried a very deep and big secret his whole life that made it hard for him to think about his relationship to other artists and other people.” He was born in 1931 in a small town in Alabama—”but not as a ‘he’ or as a ‘she.’ ” Instead, Henry exhibited qualities that might have designated him as intersex today.

Johnson, the project director, added that, as learned from Henry’s letters, the “nurse who delivered him didn’t really know what to do with him, so she just called it and said he was a girl. And that was that—that was what his birth certificate said and that was how he was raised.”

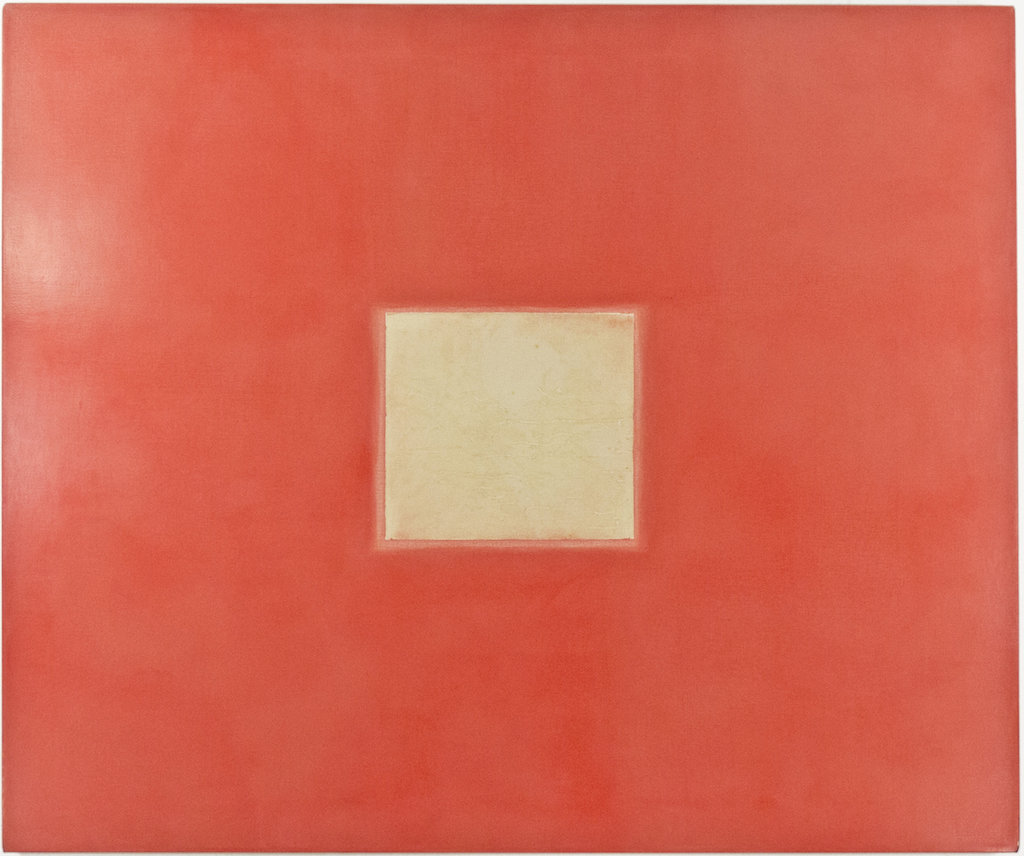

Dale Henry, Body of Work, 1976.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

Later on, as a young adult in San Francisco, Henry legally changed his gender status to male, underwent surgery, and started taking hormones that he would continue for the rest of his life. Fear of exposure might have been among the reasons he chose to leave New York, Heiss said—on top of revulsion over an art world that he felt had become alienating and overly commercially minded. Given his fear, Heiss said she wrestled over whether to make Henry’s secret known. “I knew it would guarantee attention for the shows and the museum part of the giveaway,” she said, “but we decided not to do it because we thought the whole project would become about that and all the articles would be written about that. The few press people I talked to about this honored the commitment.”

“At the end of the project tonight,” Heiss continued, “it’s time to share Dale’s secret in the light of day. Things have changed so much in the last ten years. It’s remarkable the world we’re looking at now, with Dale’s rising prominence in museumology and his presence in the collections of artists and friends who will treasure his work without anything to do with that. He was a man who had many, many things on his mind, and he was thinking about many, many ways in which to live and make art.”

—

The following is what I read at the event in response to an invitation to talk about my experience as a journalist with the life and work of Dale Henry, including how much or little biography might matter in matters of thinking about art. It was delivered prior to Heiss’s disclosure at the end, though with the prospect of that eventual reveal in mind.

I first learned about Dale Henry from Alanna Heiss and wound up writing an article about him for another publication (prior to starting at ARTnews) in 2013. As a freelancer then pitching story after story with the hope that some reasonable percentage would get a green light, Dale’s was a rich one—and it didn’t take a lot of prodding to get an editor on the hook.

There was the tale of the artist choosing to up and leave New York, with no small amount of disdain for a city that had come to seem grotesque and alienating in a way it has made a habit for ages. Then there was the element of it that spoke to the development of the art market at a historic time when talk of such things was getting going on a larger scale—plus the resonance that has with talk of the same kind continuing now. And then there was the more personal element, which really got me intrigued, of just what it meant for Dale to leave all his work to Alanna with such specific dictates about what could and should be done with it. What a tribute! But what a burden. What a generous gesture! But what presumption on his part. I of course don’t know much about how Dale thought about it all exactly, but learning of the story for the first time, you can’t help but arrive at questions of the kind before long.

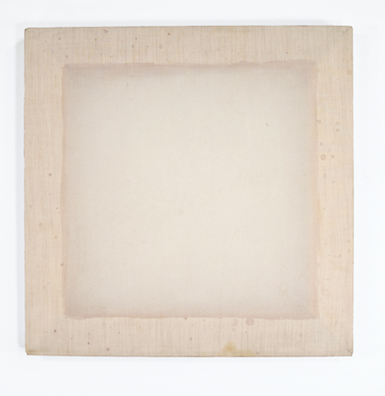

Dale Henry, Blue Tree, ca. 1964.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

Anyhow, for the Wall Street Journal I ended up writing a briefer story than I’d hoped to after parts of it got cut to fit in the paper, as often happens when fitting into print is an issue. But it told the basics of the tale and had some nice pictures, including one of Alanna with her foot in a cast surveying the walls for the installation of Dale’s show at the Clocktower Gallery—the final show at the space before it closed—like a soldier whose wound would not keep her down.

While working on that story, I got to attend a discussion convened by Alanna and learned more about Dale’s biography—including secrets that few others knew—and his ways of working in the world. The matter of biography is one I find myself thinking about a lot as a journalist, with both a general inclination toward stories of human interest and antennae always up for situations in which that human interest can be entertained. It doesn’t always or even necessarily very often gibe with my primary interests as an art viewer, as someone who goes to art first and foremost for the work and the work alone. But it’s there, and always very active, in any case.

Walter De Maria is one of my favorite artists, and he was not especially enamored of biographical matters figuring into the reception of his work. He effectively gave one interview in his life, early in his career, and I think he would have taken that back if he could. I like that aspect of him a lot, but also—especially as I’ve come to learn more about him from people who knew him well—it makes for a certain kind of tension. There’s the school of thought suggesting that mere human matters are nothing but a distraction, or at least beside the point of what art has to offer. But then there’s also a strong case to be made for knowledge only adding to appreciation and the resilience of art that wouldn’t—in fact couldn’t—be diminished by any amount of awareness of who made it and how and why it was made.

Dale Henry, Untitled, 1950s.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

But then again, I do like mystique. A few weeks ago I was in New Mexico on vacation with my wife, and we went to Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque, where petroglyphs—some of them 700 years old—have been painted in a kind of coded symbolic communication by Native Americans and Spanish settlers on the sides of rocks. There was signage all around the visitor center and on the hiking trails, but of a quizzical kind that seemed to want to make it known that there wouldn’t be much in the way of knowing while there. The meanings behind the petroglyphs were in many cases meant to be obscure. And then some observers think the meanings only present themselves to certain people, and only some of the time. I like that idea of meaning being elusive from an observational standpoint but also from within, from the core of what might constitute meaning itself.

One other aspect of my story with Dale Henry is that my wife and I were fortunate to be on the receiving end of the initiative to give his work away. We got The Old Bowery, a large green painting that is part of a group dated from 1971 to the late ‘90s. It hangs in our bedroom and is a prized possession of the most revered sort. As a journalist, I’m not in a position to have amassed much of an art collection, so the chance to own a painting and live with it—to look at it every day and see how it changes the more I look at it, while my capacity for looking itself changes too—has been a treasure.

So has what it has taught me so far about notions of value and time. The value of it is rich, since to be maintained in good faith, given the premise of the arrangement, is to acknowledge that it can’t ever have any monetary value at all. Its value is contingent on a lack of value—that’s value of a special kind.

And the time aspect of it is richer still. My wife and I got the painting not too long after we got married, which for the first time in my life gave me the ability to think in long spans of time in ways I hadn’t thought much of before. All of the sudden the future wasn’t a matter of weeks or months or even years but, hopefully, if the fates are kind, decades and decades more. I thought about that when the prospect of taking a painting by Dale started to become real. Given the particularity of the arrangement, I felt a sense of responsibility, and I thought a lot about what it would mean to be a custodian or a steward for a painting over time. I couldn’t ever really off-load it, so I’d better like whatever work I selected. And then only time would tell how living with it would actually play out.

I didn’t know Dale and so couldn’t really guess as to his reasoning for passing on his work the way that he did, but if getting people to think about matters so integral to art—matters of value and time and negotiating intimate relationships with the work of artists who might wish never to be known—was part of his ambition, he met with a rousing success in me.

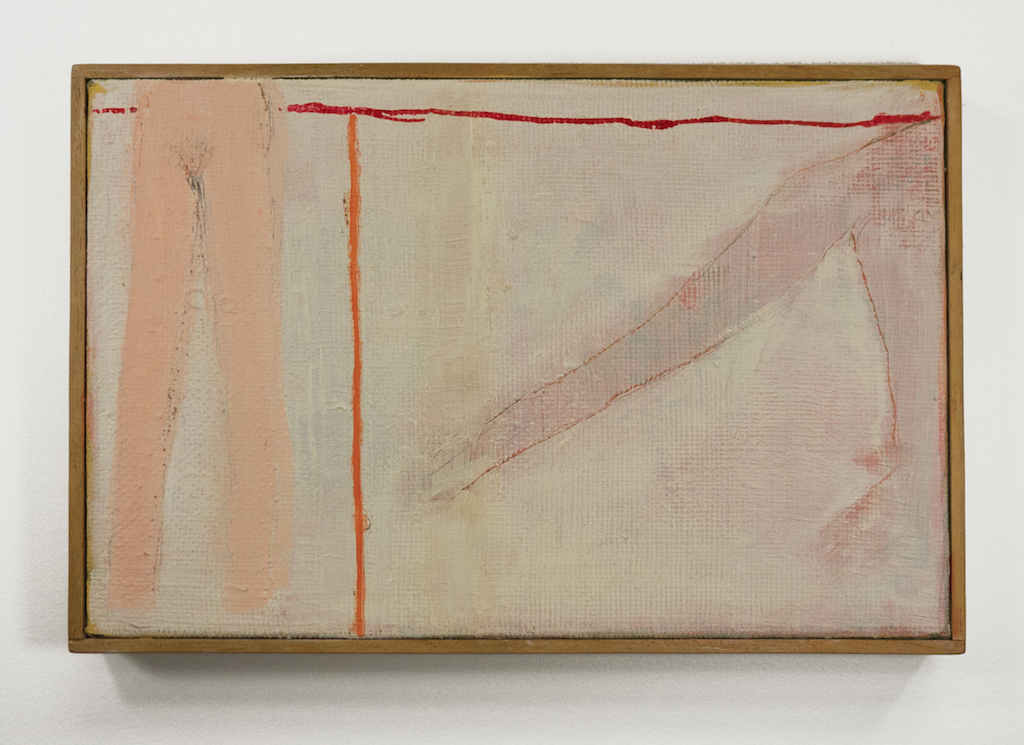

Dale Henry, Orange Running, Red Standing, ca. 1963.

COURTESY CLOCKTOWER PRODUCTIONS

[ad_2]

Source link