[ad_1]

This op-ed contains spoilers.

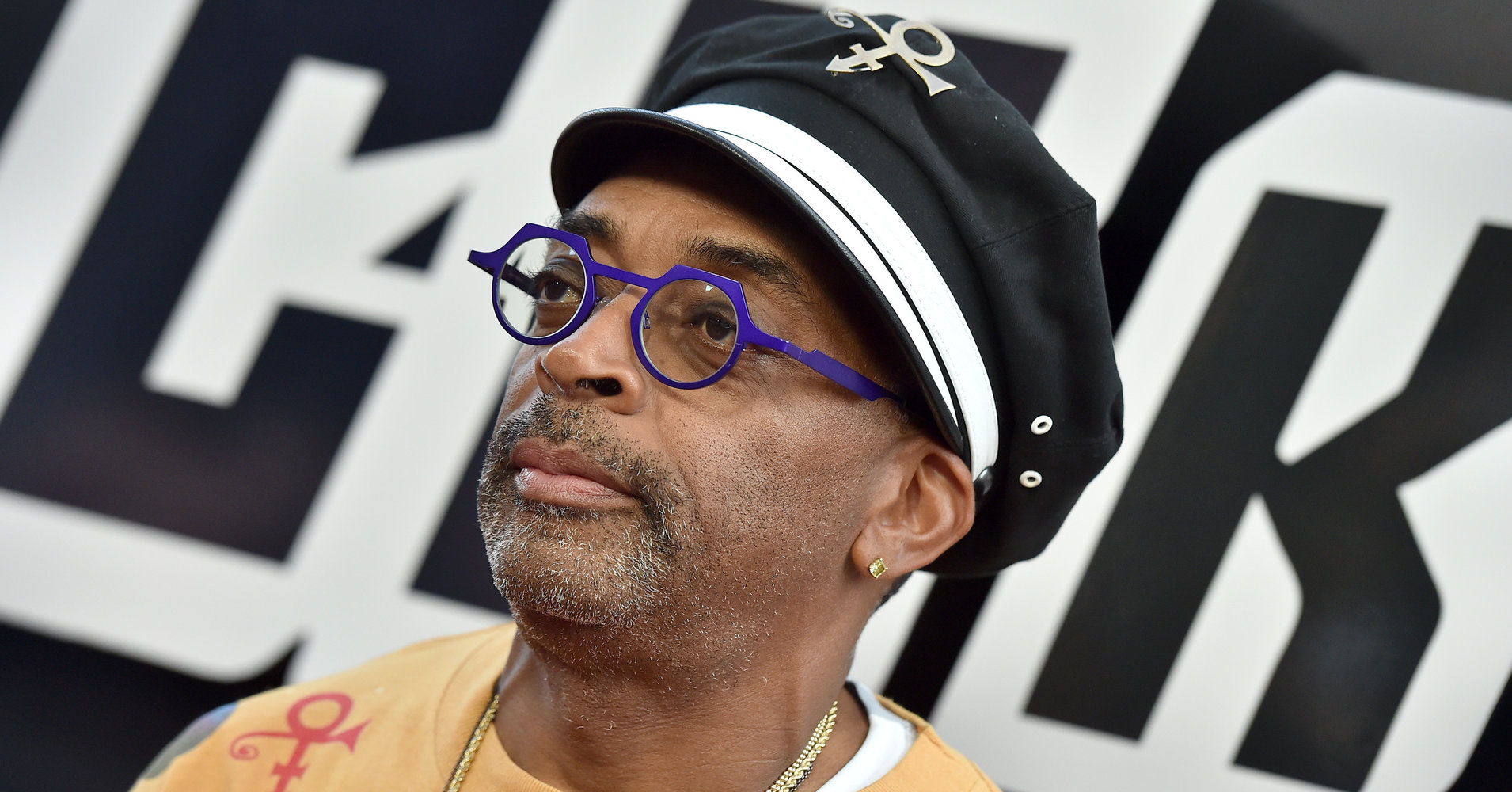

I live for Spike Lee’s provocations.

Growing up, Spike Lee’s anthropological film-length essays were vital cheat sheets on race relations, entertaining while informing me of the strange social codes and unspoken rules of life in America. This was especially true when my dad moved our family — kicking and screaming — from a comfortable, comparatively boring life in Canada, full of decency and upward mobility, to Indiana where dad got a computer consulting contract, but also where the Ku Klux Klan thrived in the 1980s and 1990s.

Before we left Edmonton when I was 10, I had not known many black people beyond my family. I had known white people all my life, but not these white people: The Indiana teachers who tried to put me on the desegregation bus back to the city with the rest of the black students even though I lived right there in the suburbs. These people seemed to know things my family did not. Where were black people supposed to live? Where was I supposed to sit in the cafeteria? What radio station was I supposed to listen to? How was I supposed to speak? There was so much to learn.

I had hoped the critically acclaimed “BlacKkKlansman” might add another layer of artistry and understanding to racism in America. But either Spike is losing his touch or I have been in America too long because the critically acclaimed film left me feeling triggered, numb and more than a little bit manipulated.

Spike Lee’s latest joint is (perhaps inadvertently) a film that seems to argue that Blue Lives Matter.

The film tells the real-life story of Ron Stallworth, a black Colorado Springs detective who went undercover to do surveillance on both the KKK and the Black Power Movement in the 1970s. That is an epic W.E.B. Dubois double-consciousness battle between the self if ever there was one.

Much of the film is a vigorous attack on past and present-day white supremacy. There are really sly and important messages about media propaganda, the racist roots of modern cinema and the KKK’s return to the White House.

But as “Sorry to Bother You” filmmaker Boots Riley points out, in the age of Black Lives Matter, Spike Lee’s latest joint is also (perhaps inadvertently) a film that seems to back the argument of the Blue Lives Matter campaign; this countermovement to Black Lives Matter argues that it is actually officers, armed with state power and money, that should be “a protected class” amid growing calls for police accountability.

The fictionalized flourishes within the movie gave the police more credit than they deserve for challenging the racism among their ranks. There’s a moment toward the end of the end of the film in which the entire Colorado Springs Police Department conspires together to oust a racist officer from within their ranks. There’s laughter and clapping and general merriment as the routine harasser is exposed and yay! The police save Patrice, the lead black woman again; first from a car bomb, now from police brutality.

Meanwhile, the film never acknowledges the cause Patrice was fighting for in the first place: the liberation of black people from a police state. Her valid complaints fall on deaf ears, and there’s nothing in the film that indicates that the Colorado Spring Police Department will stop trying to subvert her organizing. The movie lets the police off the hook for the damage they did in surveilling black people just trying to survive. Because how can we criticize the heroes who save the day?

This light-hearted portrayal of the police in the film is dangerous messaging at a time like this. As the Memphis trial of surveillance of Black Lives Matter activists gets underway this week, “BlacKkKlansman” presents a narrative that ignores the fact many local intelligence units who cooperated with federal surveillance sabotaged black communities. Today, real-life law enforcement is still using more resources on people fighting racism than the racists themselves.

Of course, we should expect a degree of artistic license from filmmakers. As the Guyanese painter Bernadette Persaud said, the artist’s job is to “tilt at the wind” and follow the stories wherever they blow. Airbrushing the police may be fine if you want to sell Pepsi to white people. I am just saying that for a black polemicist it could be a bit counterproductive.

Lee missed an opportunity to do a deep dive into how police brutality and white supremacy are linked.

This summer, I worked on a (yet-to-be published) study that reviewed narratives around Black Lives Matter in 2016, the runup to the catastrophic presidential election. In reviewing thousands of tweets and also broadcast news narratives around Black Lives Matter, there appeared to be a fundamental disconnect. The Black Lives matter protesters made an appeal for protection from police who killed indiscriminately. The Blue Lives Matter crowd made an appeal for the police to protect them from scary black “thugs.” The two opposing narratives—one anchored in fact, the other based on stereotypes and perception—reflect fears that are centuries old and as deeply rooted as the trees.

And I’m not sure if “BlacKkKlansman” helped reverse this narrative of ascendant white supremacy or buried a key source of it. The portrayal of police makes those protesting law enforcement in the film and in real life appear as though their problems are merely in their heads and not real lived experiences with violent and volatile police. What on earth could the undercover officer’s love interest have to complain about when cops are taking down white supremacy and literally saving her life? Lee, who has been widely criticized for taking money from the New York Police Department to work on an ad campaign, missed an opportunity to do a deep dive into police brutality in favor of a portrayal of the police as heroes, taking down corruption and racism from the inside out.

Meanwhile, instead of examining the ways in which the white nationalism depicted in the film and police brutality are linked, Lee gives us cartoonish depictions of the KKK members as bumbling idiots. They are so laughably stupid that it’s actually entertaining to watch them fumble through a plot to kill a black woman and her activist group. It is all good fun, but it kind of made me feel like I did back in 2016, when everyone went to sleep laughing at the joke of a political campaign only to wake up in an actual nightmare.

The portrayal of those silly Klansmen rang false when I recall being 10 years old, confused, scared to walk outside my door, fearful of my new neighbors in Beech Grove, Indiana, who seemed offended at each bit of oxygen that I had the nerve to breathe. These weren’t people who bumbled their way through Klan meetings. They were the kind of people who taught me 6th-grade social studies. They are the kind of people who supported a unrepentant racist to have the highest office in the land. They are the people who have looked the other way as people die in Puerto Rico, human children are kidnapped and caged, whole religions and regions are demonized, and who support a legal structure that forces women to have babies.

They are people with really dangerous ideas about people who looked like me. They are people with actual power, and there’s nothing silly or funny about that.

If Spike’s goal was to start a provocative and complex conversation, then he certainly succeeded. Thanks in a large part to his pioneering work to open doors to black cinema, the black experience is more than a single story or movie. There is room for multiple perspectives in art and in life. There is room for brave activists who have the audacity to fight for the value of black life in defiance of the state. We need all of that, because truly, we need all hands on deck to survive this real-life horror movie.

Natalie Hopkinson is the author most recently of A Mouth is Always Muzzled.

[ad_2]

Source link