[ad_1]

In an attempt to right its past wrongs, The New York Times launched an obituary series titled “Overlooked” earlier this year to pay tribute to the women and people of color who were not recognized by the publication at the time of their deaths, despite their amazing contributions and strides in society.

“Since 1851, obituaries in ‘The New York Times’ have been dominated by white men. With Overlooked, we’re adding the stories of remarkable people whose deaths went unreported in The Times,” states the Times.

Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis (Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

Included in “Overlooked” is Edmonia Lewis, the first black sculptor to be internationally recognized for her art. Lewis was born circa 1844 in upstate New York to a free black man from Haiti and a mother who was part Chippewa. After her parents died when she was 9 years old, she was adopted and raised by her two maternal aunts. According to the NYT, Lewis attended Oberlin College in Ohio and was mentored by leading activists and abolitionists. She later spent much of her adult life in Rome where she joined a community of American sculptors.

Her Roman studio was a required stop for the moneyed class on the Grand Tour. Frederick Douglass visited her. Ulysses S. Grant sat for her. She made busts of John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (whose 1855 poem, “The Song of Hiawatha,” inspired her to create a series of marble sculptures on Hiawatha and Minnehaha), reads the NYT obituary.

Many of Lewis’ neoclassical-style sculptures are celebrated for their portrayals of black and indigenous people. For example, one of her most acclaimed pieces, The Death of Cleopatra, depicted the iconic Egyptian queen sitting lifelessly on her throne after committing suicide.

Her sculptures sold for thousands of dollars, and she had commissions from wealthy patrons on both sides of the Atlantic. When the United States celebrated its centennial in Philadelphia in 1876, she was invited to submit her work. Her piece, “The Death of Cleopatra” — more than 3,000 pounds of Carrara marble depicting the Egyptian queen with one breast bared and quite dead — created a stir for its commanding realism, writes the NYT.

Yet, despite her talent and global recognition, Lewis was frustrated by the racial barriers she faced, particularly in the States.

In 1878, she told The New York Times: “I was practically driven to Rome, in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.”

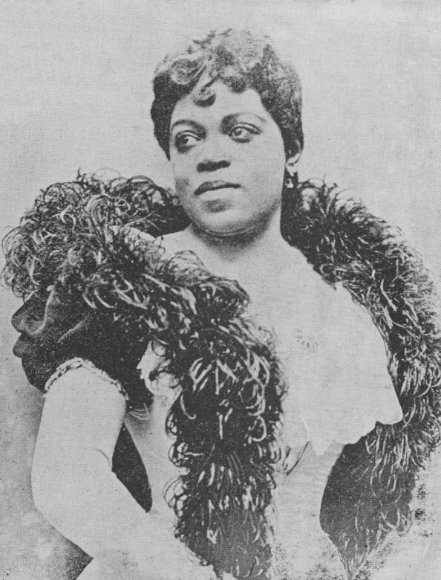

Sissieretta Jones

Sissieretta Jones (Wikimedia)

Another unsung black woman honored in “Overlooked” is Sissieretta Jones, an opera singer who became the first African American woman to headline a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1893. Born circa 1868, she became the star of a touring company called the Black Patti Troubadours. However, to her dismay, she was dubbed “the Black Patti,” which compared her to white diva Adelina Patti.

She sang at the White House, toured the nation and the world, and, in a performance at Madison Square Garden, was conducted by the composer Antonin Dvorak, reads the NYT obit page.

But there were color lines she never managed to break, like the one that kept the nation’s major opera companies segregated, denying her the chance to perform in fully staged operas.

“They tell me my color is against me,” she once lamented to a reporter from The Detroit Tribune.

When another interviewer suggested that she transform herself with makeup and wigs, she dismissed the idea.

“Try to hide my race and deny my own people?” she responded in the interview, which was published by The San Francisco Call in 1896. “Oh, I would never do that.” She added: “I am proud of belonging to them and would not hide what I am even for an evening.”

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells Barnett, in a photograph by Mary Garrity from c. 1893. Wikimedia)

The Times kicked off “Overlooked” in March with a tribute to journalist Ida B. Wells, an outspoken civil rights activist and journalist. According to the NYT:

She pioneered reporting techniques that remain central tenets of modern journalism. And as a former slave who stood less than five feet tall, she took on structural racism more than half a century before her strategies were repurposed, often without crediting her, during the 1960s civil rights movement.

Wells was already a 30-year-old newspaper editor living in Memphis when she began her anti-lynching campaign, the work for which she is most famous.

National Geographic, another publication founded in the 19th century, has also taken action this year to right its wrongs for its history of racist reporting. The April 2018 issue of the magazine included a scathing report detailing how the outlet overlooked and stereotyped people of color.

“[U]ntil the 1970s National Geographic all but ignored people of color who lived in the United States, rarely acknowledging them beyond laborers or domestic workers,” wrote the magazine’s Editor-in-Chief Susan Goldberg in the issue’s editor’s letter. “Meanwhile it pictured ‘natives’ elsewhere as exotics, famously and frequently unclothed, happy hunters, noble savages—every type of cliché.”

[ad_2]

Source link