[ad_1]

Some time ago, the writer Nikki Giovanni offered me guidance on writing about the life of a public person. Most of her advice I understood and dutifully jotted into a small notebook. However, one of her dictums confused me: “Whenever you receive a letter from a prisoner, make sure you write him back.” I frowned, confused but also a little guilty. I’d received a few letters with penitentiary return addresses and hadn’t responded. “Write them back,” she repeated. “You don’t know how much mail means to people in prison. You can’t imagine what they have to do just to get the stamp.”

Since then, I’ve heeded her advice. But sometimes it isn’t possible to write back. One gentleman I met at a book club on Rikers Island said he wouldn’t reveal his last name or ID because he couldn’t bear the disappointment of not receiving a response. Those of us who live freely in the age of electronic communication often take the mail for granted. But for people in prison letters remain the best way to engage with a society that has forcibly excluded them.

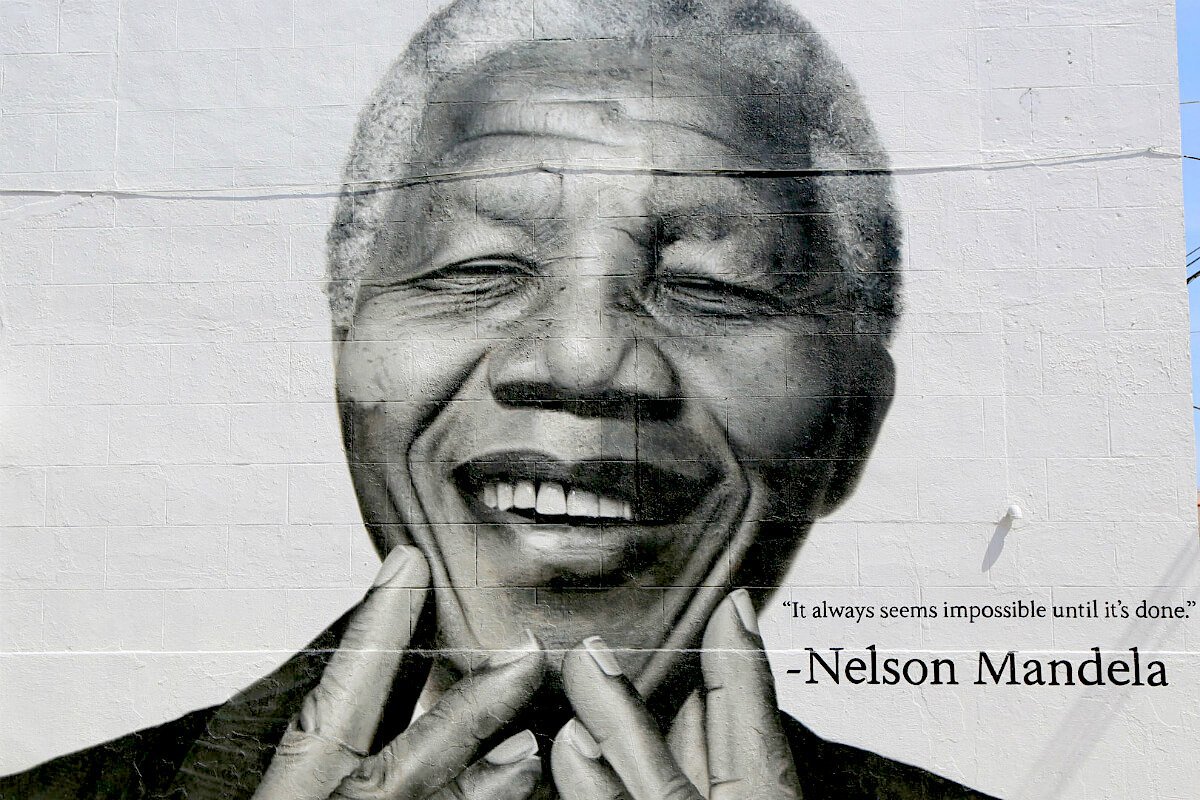

From Nov. 7, 1962, to Feb. 11, 1990, Nelson Mandela was a political prisoner in South Africa, jailed for his role as a leader in the African National Congress and its struggle against South Africa’s apartheid regime. Four years after his release he was elected his country’s president. Today, nearly five years after his death at age 95, his legacy as one of the 20th century’s most distinguished and influential freedom fighters is well enshrined. But the man himself is not completely known.

[ad_2]

Source link