[ad_1]

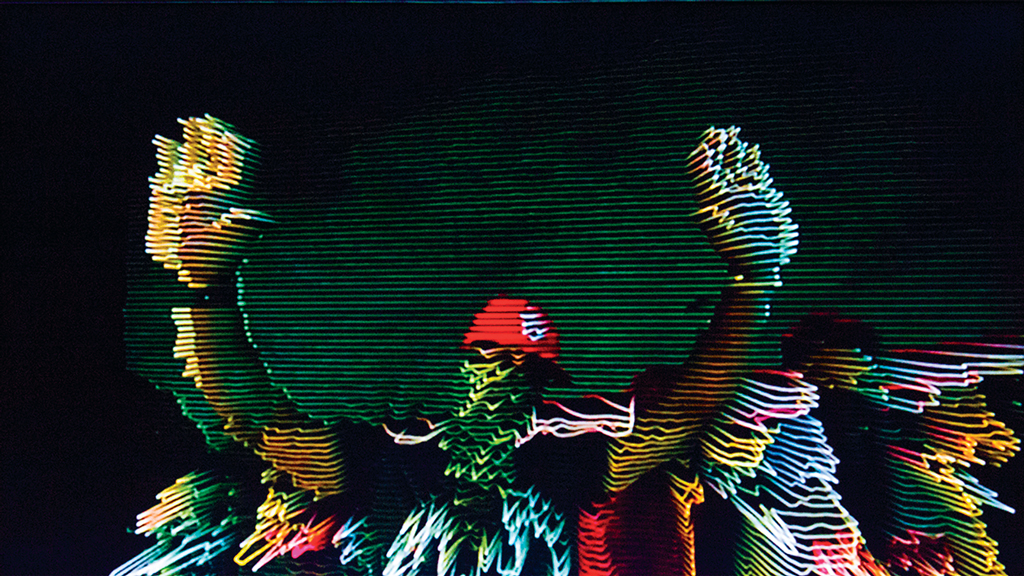

HowDoYouSayYaminAfrican?, thewayblackmachine.net (still), 2014–, 30-monitor video installation, 80″ x 30″ x 10″. Institute of Contemporary Art.

©HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?/COURTESY THE ARTISTS

Online, no one knows you’re a dog, as the oft-quoted meme goes. The internet has altered just about every aspect of ordinary life, to the point where you don’t even have to present as a human these days to have meaningful conversation. But the web is hardly the only thing to have seismic effects on the way people interact. Several museum exhibitions around Boston this past spring explored how larger forces—both digital and analog—have transformed communication over the past century.

The most notable of these shows was “Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today” at the Institute of Contemporary Art. In the past few years, there has been a slew of far-reaching surveys exploring the internet’s effects on art, including “Electronic Superhighway (2016–1966)” at the Whitechapel Gallery in London and “Art Post-Internet” at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing; there’s also the website Rhizome, which updates its Net Art Anthology weekly with new entries. Curated by Eva Respini and Jeffrey De Blois, the ICA show shared artists with these exhibitions, and offered few new discoveries to those who closely follow this type of art. Instead, it was a wide-ranging greatest-hits collection that drew a line from yesterday’s internet pioneers to today’s.

This was not a straight line. Dispensing with chronology, “Art in the Age of the Internet” instead interspersed displays of so-called post-internet works with early experiments and net.art pieces. This made for some evocative, and instructive, juxtapositions. In the first gallery, a Nam June Paik video sculpture from 1994 was shown facing the HowDoYouSayYaminAfrican? piece thewayblackmachine.net (2014–), which brought together content related to the Black Lives Matter movement—tweets, YouTube videos, low-res news broadcasts, computer-generated reenactments of police shootings—that had been lifted by an algorithm from the internet. Further on, Judith Barry’s video installation Imagination, dead imagine (1991), in which a woman’s face appears on a 10-foot-high, internal projection video cube and gets slathered in goo, was linked with Sondra Perry’s recent works about avatars; Lynn Hershman Leeson’s dolls from the mid-’90s, equipped with hidden cameras, shared space with Jill Magid’s paranoid performances from the early 2000s about women under surveillance.

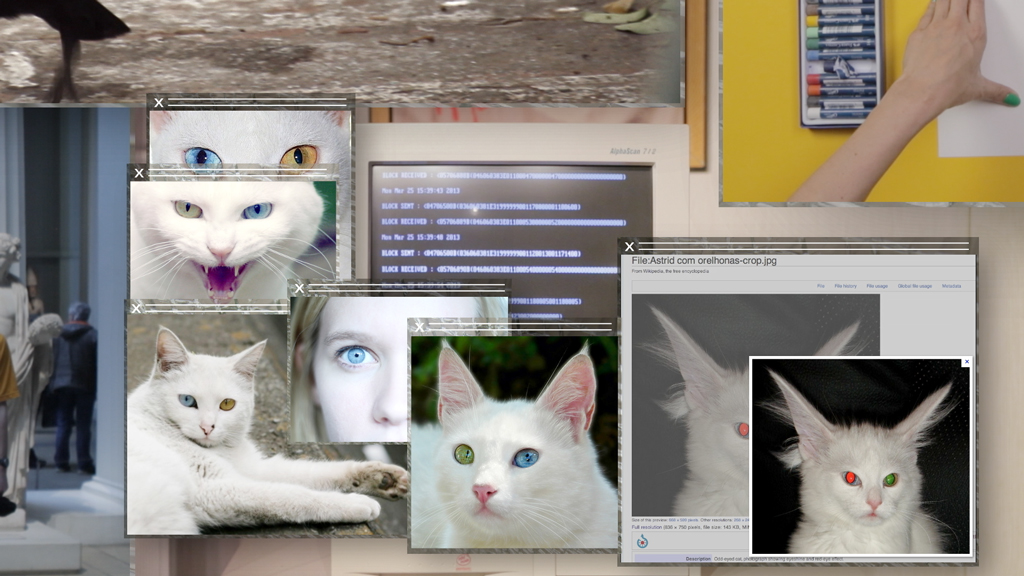

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue (still), 2013, video, 13 minutes.

©2016 CAMILLE HENROT, ADAGP/COURTESY THE ARTIST, SILEX FILMS, AND KAMEL MENNOUR, PARIS AND LONDON

“Art in the Age of the Internet” captured the full range of the online experience, from the sublime (Camille Henrot’s 2013 video Grosse Fatigue, which portrays the creation of the universe through a series of superimposed browser windows) to the terrifying (Rabih Mroué’s Fall of a Hair: Blow-Ups, a 2012 series of pixelated photographs—each showing a sniper’s gun aimed at the camera—made from zoomed-in pictures posted online by Syrian protesters in the seconds before they were gunned down). The internet is a strange, beautiful, and scary place, and this show accurately portrayed just how much one can expect to feel within a single browsing session.

Mroué’s point—that we now surf at the mercy of algorithms and surveillance technology—was picked up again and again throughout the show. Aajiao’s sculpture Gfwlist (2010), for instance, is a black monolith containing a printer that slowly unfurls a sheet of paper containing gibberish text; a wall label revealed that the nonsense was encrypted information that censors had rendered inaccessible to Chinese users. Gfwlist looked like it was acting autonomously, and its concern with sentient technologies was updated for our current moment in the show’s sole new work, Jon Rafman’s VR piece View of Harbor (2017). By means of a headset, the view of Boston Harbor through the museum’s floor-to-ceiling windows became a post-apocalyptic landscape filled with skeletons and sea monsters, one of which, over the course of eight harrowing minutes, ate this viewer, digested him, and pooped him out.

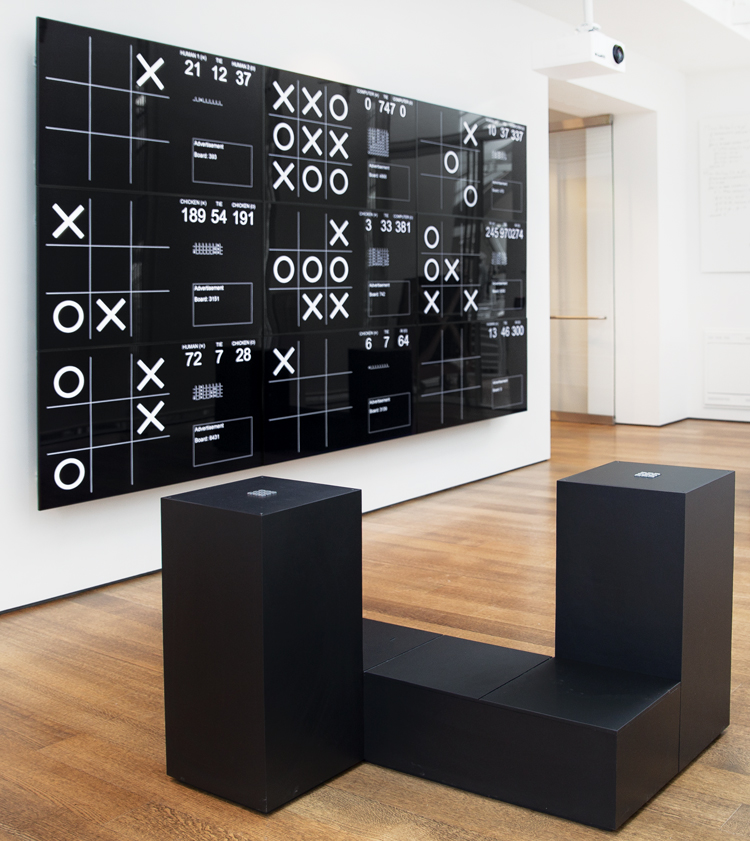

At the Harvard Art Museums, a new installation called OXO by JODI, the duo most famous for its 1990s net.art pieces that mess with the look of webpages, offered a coda to “Art in the Age of the Internet.” Using a set of unmarked buttons, visitors were invited to play several games of tic-tac-toe against a computer. A large screen offered views of the various matches being played, as well as a continuously updating counter of wins and losses. But JODI didn’t provide instructions for how to use the buttons, and the computer sometimes seemed to be acting on its own, as though no longer relying on the artists’ programming. When I took my turn, I became the 196,556th person to concede victory to JODI’s algorithm.

JODI, OXO, 2018, interactive multi-channel installation, using artificial intelligence in a game of tic-tac-toe, installation view. Harvard Art Museums.

R. LEOPOLDINA TORRES/©PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE

Feelings of defeat and resignation surfaced throughout “Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55,” also at the Harvard Art Museums. Surveys of German art in the years immediately following World War II have been few and far between, and many critics have dismissed the period as an art-historical dead zone. But “Inventur” was a fascinating look at artists struggling to find new visual languages for communicating their country’s trauma and, eventually, healing.

In the first few galleries, curator Lynette Roth showcased work that responded to a permanently altered German landscape. Abstractions by K. O. Götz, Hannah Höch, Erwin Spuler, and others resembled explosions and broken buildings, while Gerhard Altenbourg and Karl Hofer depicted flayed and decaying corpses. Some of these pieces were so-so reworkings of Modernist strategies (Hermann Glöckner’s angular copper sculptures felt a bit like Constructivist knockoffs); others were real discoveries (Siegfried Lauterwasser’s captivating photographs of cityscapes reflected in German lakes).

Ruth Hallensleben, Untitled (Advertising Photograph of Wallpaper by Pickhardt & Siebert, Gummersbach), 1955, gelatin silver print, 9⅛” x 6⅞”. “Inventur,” Harvard Art Museums.

HARVARD ART MUSEUMS/BUSCH-REISINGER MUSEUM, GIFT OF THE CULTURAL COUNCIL IN THE FEDERATION OF GERMAN INDUSTRY

As it traced a bombed-out German art scene rebuilding itself, “Inventur” sprang to life. Its final galleries were a high point: artists let loose following a short-lived economic boom, thanks to the introduction of the deutsche mark. Work by women—often written out of postwar German art history in favor of their male colleagues—stole the show here. A highlight was Ruth Hallensleben, whose dazzling black-and-white photographs of consumer objects—a mod radio posed against patterned wallpaper, for example—are simple pleasures. With their blurring of advertising and avant-garde strategies, they feel particularly prescient.

Next door, at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, a Renée Green show also mined history for obscure, intriguing odds and ends. Her three-year residency at the museum culminated in Green’s taking over the entirety of the Carpenter Center, placing her essayistic videos and cryptic photographs in gallery spaces, temporary environments, and a display case in the building’s basement, and even on the museum’s facade via a projection. It was a master class in how a space can reveal its history through texts, artworks, and objects.

Green’s work confounds more often than it reveals—her art piles on references to theory and philosophy, usually in ways that are difficult to understand, even for the most worldly viewers. Yet her videos, which take their cues from the essay films of Chris Marker and Harun Farocki, reward patient attention. Begin Again, Begin Again (2015), a video prominently placed in the museum’s lobby, links together a building in West Hollywood designed by Rudolph M. Schisndler and the history of Vienna, all while a narrator counts down more than a century of years, from 1887 to 2015, and muses on the ways ideas are lost and traded. “Take me to the other end of the city, where no one else wants to go,” a narrator says at one point over a montage of subway cars drifting through tunnels, people dancing in a strobe-lit club, and pine trees in a forest. It’s not hard to imagine Green having thought this to herself while wandering the streets of European cities in search of hidden histories, as she does in a few videos here.

Maria Vedder, PAL oder Never the Same Color, 1998, color-and-sound video installation with 25 monitors, 5 minutes, 32 seconds. “Before Projection,” MIT List Visual Arts Center.

COURTESY THE ARTIST/PRODUCED BY MUSEUM LUDWIG KÖLN, GERMANY

Green’s output would not have been possible without the innovations of early video artists, whose work, which often explored the connection between people and environments, was surveyed in the thrilling MIT List Visual Arts Center exhibition “Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995.” During the exhibition’s two-decade time frame, projectors were expensive and heavy, and many institutions couldn’t support exhibiting works that made use of them. In response, video artists resorted to placing monitors within sculptures and installations—alongside a ping-pong table, in one Ernst Caramelle piece, or inside a model of a medieval-style castle, in a Tony Oursler.

Many of these artists were using television technology to subvert television’s banal comforts. An incisive Maria Vedder installation pondered the visual differences between American and international network broadcasts of color TV shows, while a 1984 Muntadas video called Credits was merely a series of closing credits sequences appropriated from various programs: entertainment, minus the entertainment.

Yet these works were nowhere near as aggressive as the exhibition’s crown jewel, Adrian Piper’s 1990 installation Out of the Corner. It featured a pyramid of monitors, each with an upturned chair in front of it, that was arranged inside a gallery ringed by images of black women re-photographed from Ebony magazine. While the Sister Sledge song “We Are Family” played, the monitors would occasionally turn on, and various people, including the artists Gregg Bordowitz and Andrea Fraser, would say that their ancestors were called “house niggers” and raped by slave masters, and that, if the viewer was American, hers probably were too. This means the viewer may be black, according to the one-drop rule, which holds that a person is black if anyone in their lineage identified as such. Eventually, a monitor in the back corner turned on, and Piper, looking directly at the camera, asked what the viewer would do with this information. Piper said that if she herself identifies as black and the viewer doesn’t, “it’s our problem to solve.” Eventually, her image disappeared and was replaced by a title card: WELCOME TO THE STRUGGLE.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 104 under the title “Around Boston.”

[ad_2]

Source link