[ad_1]

WASHINGTON ― There is nothing President Donald Trump loves more than winning. On May 24, surrounded by some of the most conservative Republicans in Congress, he savored the second major legislative victory of his presidency by signing into a law a bill that rolls back a host of bank regulations adopted after the 2008 financial crisis.

“By liberating small banks from excessive bureaucracy ― and that’s what it was, bureaucracy ― we are unleashing the economic potential of our people,” Trump declared, as Fox News favorites like Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) and Rep. Sean Duffy (R-Wis.) smiled for the cameras. Grinning alongside them was Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-N.D.), who earned a prominent spot next to the president for helping organize the Democratic votes needed to get the bill through Congress.

Up for re-election this fall in deep-red North Dakota, Heitkamp is one of only a few sitting Democrats who believe a photo op with Trump will boost her prospects in November. Joining her and the GOP in supporting the bill were 16 other Senate Democrats, several of whom are also up for re-election this year in states Trump won. To judge by the flurry of enthusiastic press releases issued by the bill’s supporters, Washington was experiencing a rare moment of bipartisan comity.

But behind the signing-day smiles was the most bruising intraparty fight in recent memory ― one that has left Democrats of every ideological stripe fuming as the party struggles to renegotiate its rules of fair play in the Trump era.

“The anger and frustration has lasted,” said one Senate Democratic aide. “It has not subsided.”

After spending 18 months lambasting the president for showering money on the superrich and pursuing a racist agenda, more than a third of the Democratic Senate caucus voted for a bill that will swell the fortunes of bank shareholders and executives as it weakens protections for consumers and could allow for more racial discrimination in the housing market.

HuffPost spoke with more than a dozen Democratic senators, aides and advocates about what happened behind the scenes as the bill made its way to Trump’s desk. Most requested anonymity in order to speak candidly about an emotionally charged battle between friends and allies.

The inflamed tempers don’t really have all that much to do with financial policy. They’re concerned with much more sensitive Washington intangibles ― the unspoken etiquette that binds lawmakers into coalitions and the way politicians navigate the difference between compromise and corruption. The 2016 presidential election showed Democrats that its old rules were obsolete. But if the bank bill fight is any indication, they’re still figuring out a new way of doing business.

Going Around Tradition

The Senate banking committee is one of the few congressional panels with a genuine ideological split between its ranking member and rank and file. The committee’s top Democrat is Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, who built his career as an anti-corporate populist. He supported the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial overhaul and was one of just 33 senators who voted for a failed effort to break up the six largest banks that year.

Brown’s chief ally on the committee is Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). But other Democrats ― such as Heitkamp, Jon Tester (Mont.), Mark Warner (Va.) and Joe Donnelly (Ind.) ― have more flexible relationships with the financial sector.

It isn’t an accident that these self-described moderates all hail from red or swing states. Both parties view a seat on the banking committee as a fundraising opportunity. It’s a place where vulnerable senators can advocate for corporate interests, hoping that companies will return the favor by contributing to their campaigns. Freshman Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada was assigned to the committee last year, as was Sen. Doug Jones after his surprise December victory in Alabama.

Being a ranking member isn’t nearly as much fun as being chairman of a committee, but it’s the best any Democrat can hope for right now. Ranking members set party protocol on legislation under their committees’ purview. They cajole and corral reluctant senators from their party on committee votes and shoulder responsibility for cutting deals with the committee chair when Republicans are interested in negotiating.

This is all according to Senate tradition, not formal rules. Any Democrat can cut a deal with any Republican on anything, anytime. On small bills, that’s standard practice. Most banking legislation is introduced with at least one co-sponsor from each party. These items never make it into law on their own. Instead, they get rolled up with dozens of other tiny things into something big and important. What ends up in the package and on what terms is where the ranking member really exercises power.

Unless he doesn’t. When Nevada’s Harry Reid was the Democratic leader in the Senate, bank deregulation bills didn’t get a floor vote. Reid wasn’t a die-hard financial reformer, but he didn’t like forcing his caucus to take tough votes that pit the values of most Democratic voters against the interests of rich donors. With Reid’s standing threat to filibuster bank deregulation, Brown’s moderate underlings had no real incentive to freelance with Republicans, since the entire party would eventually be ordered to vote against a deregulation bill on the floor.

Reid retired in 2017, and Chuck Schumer of New York succeeded him as minority leader. Although Schumer didn’t write a word of the bank bill or even declare a party line on the final product, the law Trump signed last week is as much his handiwork as the president’s.

Brown began bargaining with the Senate banking committee chairman, Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), last year over a bill that would have lifted regulations on banks with $10 billion or less in total assets ― a group typically described in Washington as community banks, though its executives are more likely to be pinky-ringed millionaires than hardscrabble George Baileys. Community banks account for the vast majority of American banks but only a small fraction of the lending market, since a handful of multitrillion-dollar behemoths dominate the financial sector.

As the talks proceeded, Brown was even willing to lift some risk-management rules on big regional banks ― like Key Bank, BB&T and SunTrust — as long as he got stronger consumer protection standards as part of the deal. But Crapo wouldn’t budge on consumer help and kept insisting on perks for behemoths like Citigroup and Deutsche Bank. After several months of wrangling, Brown dropped the talks.

Almost immediately, Warner, Tester, Heitkamp and Donnelly began their own negotiations with Crapo. Schumer never formally deputized anybody as his representative, but unlike Reid, he didn’t stand in their way and maintained lines of communication with the negotiators. The moderates insist they kept Brown in the loop, that although they were undermining his authority, they didn’t lie to him about it.

“We just do our own thing,” Donnelly told HuffPost. “We work hard. We didn’t look for support or anything.”

But the group announced a deal with Crapo just two weeks after Brown walked away from the negotiating table ― enough time to tweak some provisions and show lobbyists which senators were moving in to save the bill but not enough time to significantly rework anything.

“Democrats didn’t have to do this,” said Chad Bolt, an associate policy director for Indivisible, a progressive advocacy group. “If they wanted to pass a community banking bill that was limited to helping community banks, they could have, because Republicans couldn’t have passed it without them. There’s a reason why they stood by and let deregulation of some of the biggest banks in the country sail through.”

Ultimately, 25 of the 38 largest financial institutions will be exempted from the most stringent postcrisis rules reining in risk taking. “Clearly the distress or failure of some of these banks could trigger reactions spreading broadly to the financial system,” former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker wrote in a letter to Brown.

By early December, Heitkamp, Warner, Tester and Donnelly were distributing a two-page explainer to other Senate offices and the press attempting to dispense with liberal concerns about the bill. Critics were blowing the deal with Republicans way out of proportion, they insisted. It was really about small banks ― the kind of institutions Brown had been OK with helping all along.

The claims in the document are technically accurate. Only someone accustomed to dealing with Wall Street attorneys would have been able to detect their dishonesty. One section, for instance, denies that the legislation “would gut oversight of foreign megabanks,” insisting that “Deutsche Bank, [Barclays] and Credit Suisse will still be subject to Section 165,” ― the part of Dodd-Frank that requires “enhanced supervision” of the largest American banks.

What the document didn’t say, however, was that the bill would amend Section 165 to exclude a ton of big banks ― including Deutsche Bank, Barclays and Credit Suisse ― from the tougher oversight standards. When Dodd-Frank passed in 2010, Section 165 stated that banks with $50 billion or more in assets would be subjected to the most stringent rules. The new bill raised that threshold to $250 billion. Since Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Barclays all have less than $250 billion in assets in the United States, all three will enjoy reduced oversight.

To the inexpert, it looked as though Warner, Heitkamp, Donnelly and Tester were saying Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank would continue to be regulated like Goldman Sachs, when in fact the bill would treat them like New York Community Bank.

Tester, Warner, Heitkamp and Donnelly couldn’t get any other Democrats to vote for the bill in committee. But they solicited co-sponsors outside the panel to strengthen their hand on the Senate floor and prevent more liberal senators from softening the package with amendments. They weren’t just going around Brown; they were going around the entire committee process.

Months later, when the bill became the subject of screaming matches between senators and staffers in private meetings, this early tactical maneuvering became a focal point for outrage. Most senators aren’t financial experts. They rely on reports from their banking committee colleagues. Sure, the Congressional Budget Office released an analysis concluding the legislation will increase the risk of a financial crisis, and fair housing advocates said it would hurt families of color. But to cut the feet out from under a ranking member and mislead other senators? These were serious breaches of decorum.

“They totally screwed Brown on process,” an aide to a Democratic senator who does not serve on the banking committee told HuffPost. “It looked terrible.”

Follow The Money

The money trail on the bank bill isn’t terribly difficult to follow. In late April the American Bankers Association, the top lobbying vehicle for banks both large and small, announced an ad buy supporting Tester’s re-election bid. It’s the first time the ABA has produced its own advertisements on behalf of specific candidates; typically the organization prefers to just fork over cash to the candidates. The first ad, with $125,000 behind it, is a charming spot featuring friendly white men reassuring Montanans that “local banks build local businesses.”

“Sen. Tester put politics aside and voted to cut the red tape,” the ad states, praising his “leadership” and “courage.”

In April, weeks before the ABA announced the ad buy, Tester told Politico his vote was about giving small banks some regulatory breathing room against New York behemoths. “Wall Street banks won’t serve rural America, they won’t serve Montana. Goldman Sachs isn’t coming out here, Citibank isn’t coming out here. So what will rural America do?” he said.

Whatever economic issues are plaguing Montana ― agricultural prices have been falling steadily for years ― the health of its banking system isn’t really an issue. No Montana-based bank has failed in the 21st century, according to the FDIC. The 48 banks headquartered in the state currently employ 6,929 people, about 600 more than a year ago, and booked a combined profit of $445 million last year, up from $411 million the year before.

No North Dakota–based bank has failed this century either. True community banks are generally doing quite well. Nationwide, they enjoyed a combined profit of over $6 billion in the first quarter alone, up more than 17 percent from the first quarter of last year.

It is true that the banking industry has been undergoing a period of massive consolidation since the early 1990s, when Congress began passing deregulatory laws encouraging blockbuster mergers. The industry will continue its monopolistic lurch unless Congress passes laws to discourage such mergers.

Laws like the one Trump just signed will probably accelerate that trend. The biggest winners under the bill are large regional players with $50 billion to $250 billion in assets. Freed to expand up to fivefold without shouldering further regulatory burdens, such banks will go on a buying spree, industry analysts say.

When HuffPost asked Tester whether he was surprised by the reaction to the bill, he shrugged off the criticism, saying, “It’s Congress. No matter what happens, you get blowback. It’s just the way things are.”

But it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the Democrats who voted for the bill were making an election year gambit for campaign contributions.

Heitkamp, for instance, received a thank-you for her support of the bill from the conservative movement, which often works hand in glove with the financial industry: Americans for Prosperity, founded by Charles and David Koch, released a digital ad campaign on her behalf.

Commercial banks made a tremendous push to win over Democrats in the 2018 cycle. These are firms that focus on business lending rather than high-flying securities trading, and they come in all sizes, from small community banks to regional giants and even specialty units of Wall Street monstrosities. Seven of the industry’s 10 favorite senators this year are Democrats, according to the Center for Responsive Politics’ list of top recipients of contributions from commercial banks, with Heitkamp and Donnelly at the top, accompanied by Tester, Jones, Tim Kaine (Va.), Claire McCaskill (Mo.) and Debbie Stabenow (Mich.). All of them but Jones are up for re-election in the fall in a competitive state. In the 2016 elections, no Democratic senator made the industry’s top 10.

Senators do publicly unpopular things because they think voters aren’t really paying attention and believe the marketing that hits the airwaves during campaign season will outweigh any bad press in the interim. It’s not a crazy calculation. But it may well be wrong. Brown represents a state Trump won in 2016, as do Sens. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.) and Bob Casey (D-Pa.). All three voted against the bill.

“Quite apart from the very bad policy in the Crapo bill, the days when you can neutralize the very bad politics of bank deregulation by simply labeling a bill as bipartisan and all about community banks are long gone, if they ever existed,” said Carter Dougherty, a spokesman for Americans for Financial Reform, a coalition that opposed the bill. “We’re in a world where the public, across parties and demographics, believes we need tougher regulation of the financial services industry.”

And the red-state Democrats’ decision to cut a deal with Crapo came at a cost for Brown, who voted against the legislation and didn’t get to lead a bill providing some relief to community banks. Brown, after all, is up for re-election in 2018 as well.

‘Blood And Teeth On The Floor’

Individual senators are nevertheless extremely reluctant to lecture other senators about their political survival. Performing elaborate favors for $100 billion banks may not be regarded as a virtue in Democratic Party circles, but everybody knows you can’t get elected without raising money from somewhere.

The bank bill, however, wasn’t a fundraiser in the Hamptons. It was a piece of legislation that would change public policy — one that needed support from at least 10 Democrats to overcome a filibuster and get to Trump’s desk. With the GOP unanimous in its support, Warren trained her sights on her fellow Democrats, hoping to peel off enough members to sustain a filibuster.

Though her colleagues and cable news talk shows usually describe her as a leader of the party’s left wing, on most policy questions, she’s difficult to distinguish from her middle-of-the-road peers. She has earned her reputation by refusing to regard backroom deals with corporate America as the normal, acceptable price of progress.

That and her way with words. When Democrats were negotiating the 2010 Dodd-Frank reforms, Warren wasn’t even in Congress, but she still managed to stun Washington officialdom by declaring that she would put “plenty of blood and teeth on the floor” in the struggle to create the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. This time around, she used the same unsparing rhetoric against her Democratic colleagues in press interviews and on her social media accounts. Even when other Democrats think she’s right, it can leave them feeling bitter.

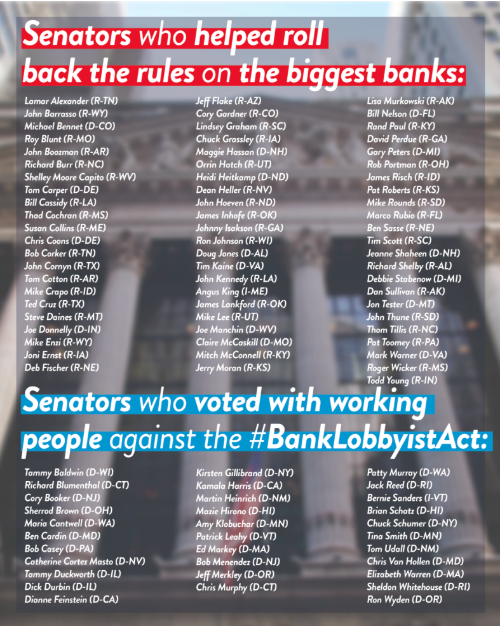

But Warren’s campaign emails really got under their skin. Since February, she has issued at least five emails to her supporters criticizing Democrats for teaming up with Republicans on the bank legislation. The most biting was an email in early March, when her campaign named all her colleagues who voted with Republicans. “We want everyone to know whose side their senators are standing on this week: the big banks or the American people,” she wrote. The email included this graphic:

At the bottom of the email was a “donate” button. Warren’s missive sent shockwaves through the Democratic caucus. Whereas her opponents were trying to raise money from banks, Warren was trying to raise money by publicly humiliating other Democrats.

“Some of the criticism was just flat wrong, and some of it was unfair,” McCaskill told MSNBC in March.

In private, tempers flared much hotter. At a meeting of Democratic chiefs of staff in March, staffers for the senators who supported the bill confronted Warren’s chief of staff over her campaign emails. The aides for the red-state Democrats up for re-election this year took a backseat, and some of their colleagues went to bat and defended them. Attendees said it was very contentious, with shouting on both sides.

“She didn’t need to create all these enemies to reinforce her brand as a warrior against Wall Street,” one Senate Democratic aide said.

“I think Elizabeth obviously feels very strongly that the bill that we crafted went too far,” Heitkamp told HuffPost. “I don’t share her read on that. I’ve been pretty clear based on my statements on the floor that what we did was not accurately or fairly represented in those statements.”

Schumer had a meeting with Warren in which he relayed concerns about her tactics.

She is a genuine financial expert whose academic research into consumer bankruptcy revolutionized the study of economic inequality in the 1980s. She has decades of experience communicating complicated financial ideas to the public. Democratic voters trust her. Multiple Democratic Senate staffers told HuffPost that once she started speaking out about the bank bill, there was just no way for its supporters to overcome her framing. Whatever anybody else says, Warren always has the final word with Democratic voters when it comes to the financial sector.

“Sen. Warren importantly spoke truth to power, critiquing those who supported the rollbacks of critical public protections for Main Street Americans,” said Lisa Gilbert, the vice president of legislative affairs at Public Citizen. “Honest assessments of those who do the wrong thing are welcome and needed, as Wall Street dollars impacted policymakers.”

Buckle Up For 2020

Tim Kaine didn’t begin his career as a corporate Democrat. A onetime civil rights lawyer who opposed the death penalty in what was still a red state during his successful 2005 run for governor, Kaine never drew many complaints from the left. But he’s been quietly drifting right on regulatory issues in recent years.

In 2015 he backed bipartisan legislation designed to make it harder for bank regulators and the Environmental Protection Agency to curb abusive corporate behavior if doing so would cost companies money. A year later, he signed a letter to then–Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen asking her to ease up on the risk management requirements for large regional banks and another letter to then–CFPB Director Richard Cordray asking him to exempt small banks and credit unions from consumer protection rules. In April he helped turn those letters into law by voting for the bank bill.

Kaine’s office insists he stands by it as a win for “rural and underserved communities.” But plenty of people on Capitol Hill think he has some regrets about the deal he signed onto, particularly a section that curtails the government’s ability to monitor racial discrimination in the housing market.

Since the 1970s, federal law has required lenders to turn over basic information identifying the race of mortgage applicants and whether they are approved for a loan. Dodd-Frank significantly expanded this program to include information on borrowers’ age, their credit score, the value of the home being purchased, the interest rate and other pricing features. The idea was to track not just whether families of color were being denied loans but also whether they were being regularly overcharged or steered into predatory products.

The bank bill exempts about 85 percent of banks and credit unions from these new rules. It’s the smallest 85 percent of banks, which control only a small fraction of the overall housing market. But the data blackout will be concentrated in neighborhoods and regions that face a particularly high risk of discriminatory mortgage practices: urban cores and rural peripheries.

According to an analysis by the CFPB, the item will save genuinely small banks roughly $1,900 in paperwork costs each year, plus about $3,000 in up-front transition costs.

A week after HuffPost ran a story highlighting the provision, Kaine submitted an amendment that would have effectively eliminated the exemption. It was a peculiar gesture. By submitting the amendment, Kaine acknowledged there was a serious problem with the bill. But there was no chance the amendment could get a vote; if Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) started allowing liberal senators a vote on individual provisions they didn’t like, it could jeopardize a package that more than a dozen Democrats had already endorsed. And when the amendment didn’t get a vote, Kaine backed the bill anyway.

“I’m disappointed we weren’t given the opportunity to vote on more amendments, including one I proposed to make the bill better,” he said in a written statement the day the bill passed.

Kaine has never been a power broker in the Senate, but his vote carries symbolic significance. He was the party’s vice presidential nominee in 2016, and unlike other recent losing-ticket VP picks, he’s still well liked by the party’s base. For some staffers who want to see the party learn from its mistakes, Kaine’s bank bill vote reminds them of painful answers to questions about paid speeches to Goldman Sachs.

For others, the conflict is a sign of growth. The party is changing and has to grapple with real internal disagreements before the 2020 election. Every senator rumored to have presidential ambitions voted against the bill ― Warren, Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and even Cory Booker (D-N.J.), who has long earned the ire of progressives for his finance-friendly comments.

“If this is our big blow-up,” Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) told HuffPost, “we’re doing pretty well.”

But the bank bill isn’t the first set of fireworks to go off ahead of 2020, just the most intense. In 2017, Booker took heat from the left for voting against a (largely symbolic) Sanders proposal to allow Americans to buy prescription drugs from Canada. In February, Harris infuriated many of her colleagues when she was one of just three Democrats to vote against a bipartisan immigration compromise that was opposed by immigrant rights groups.

Senators and staffers generally understand these conflagrations in terms of personal rivalries and professional etiquette. They see the party’s activist base as an amorphous faction controlled by noisy lawmakers trying to make names for themselves. But Warren didn’t make the bank bill unpopular by deploying underhanded wizardry against the party’s impressionable young base. The financial crisis fundamentally changed the way many Americans understand corporate power. The question is whether that means anything on Capitol Hill.

[ad_2]

Source link