[ad_1]

By Maria Anderson

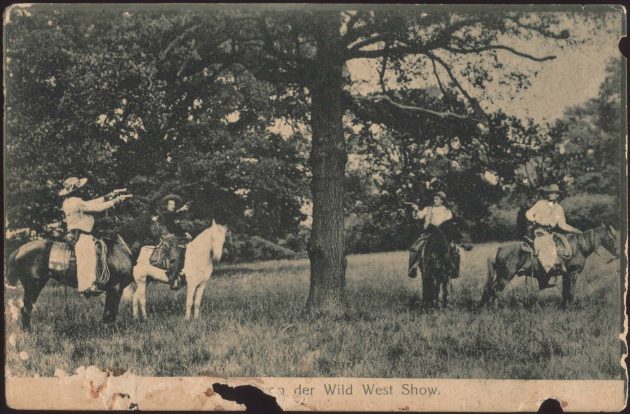

“Erased Lynching Series: der Wild West Show,” (Set 1) by Ken Gonzalez-Day, 2006. (Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles)

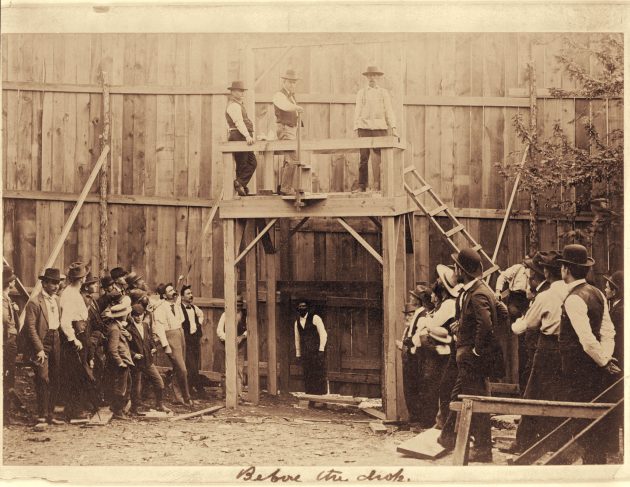

An old black-and-white photograph shows a crowd of people gathered around something, but it is not clear just what. There’s something eerie about it but you don’t really know why. The photograph is of a lynching that took place in Texas in 1915. Missing from the image is the body of the victim.

Los Angeles artist Ken Gonzales-Day takes historic photographs of lynchings and removes the victims’ bodies from them to address the erasure of certain minorities from historical accounts of lynchings.

“While researching images of Latinos in California and the Southwest, during the turn of the 20th century, I came across a lot of cases of Latinos who had been lynched,” Gonzales-Day says. “I realized that I didn’t know much about this history and, as a Mexican American and a California native, I wanted to find out more.”

“Erased Lynching Series: Leo Frank (Atlanta, Ga. 1915) (Set II) by Ken Gonzales-Day, 2013. (Courtesy the artist and Luis de Jesus, Los Angeles)

Since there are no books on the subject, Gonzales-Days worked with primary sources, reading hundreds of newspapers published at the turn of the 20th century, looking for accounts of Latinos who had been lynched.

What he found surprised him: Although they were only 5 percent of the population at the time, Latinos made up 44 percent of lynching victims in California.

“During the American expansion west, many groups other than African Americans became the targets of racial violence,” explains Taína Caragol, curator of Latino Art and History at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Gonzales-Day’s work is currently featured in the exhibition “UnSeen: Our Past in a New Light, Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar” at the museum.

Along with Mexican Americans, people who were African American, Native American, Chinese American and Jewish were also targeted for lynching.

In his “Erased Lynchings” series, Gonzales-Day identifies each photograph using as much information as possible, such as a victim’s name and the year and the state where the lynching took place. He removes the victims from the images to avoid their re-victimization, while drawing attention to the crowd, which in many instances includes the perpetrators.

“Erased Lynching Series: The Hanging of Percy Hand on Stouts’s Marsh (The Taylor Bros., 1912) (Set II) by Ken Gonzalez-Day, 2006. (Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles)

“As an artist, I tried to figure out how to present the information I found through my research,” Gonzales-Day says. “I erase the bodies to create a space for people to think about what is missing but to also put an emphasis on what remains, which is the social conditions that made these racialized killings possible.”

“At the time it was common for photographers to take photos of lynching victims and the people gathered around them,” Caragol explains. “It was a whole industry. Those gathered would pose for photos next to the lynching victim and send them as postcards to friends and family.”

The artist hopes visitors walk away with a broader view of the nation’s history of lynching and how it goes beyond the African American experience.

Erased Lynching Series: Before the Drop (c. 1896), by Ken Gonzales-Day 2013. (Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles)

“I hope people consider all the communities that have been targeted at various times in our nation’s history and try to rethink our stance on human differences,” Gonzales-Day says.

His interdisciplinary research has also led Gonzales-Day to publish a detailed historical account of lynching in California, which expanded the number of known lynching cases from 50 to more than 350 in that state. Published in 2006, “Lynching in the West: 1850-1935” was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

“UnSeen: Our Past in a New Light, Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar” is on view through Jan. 6, 2019 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

[ad_2]

Source link