[ad_1]

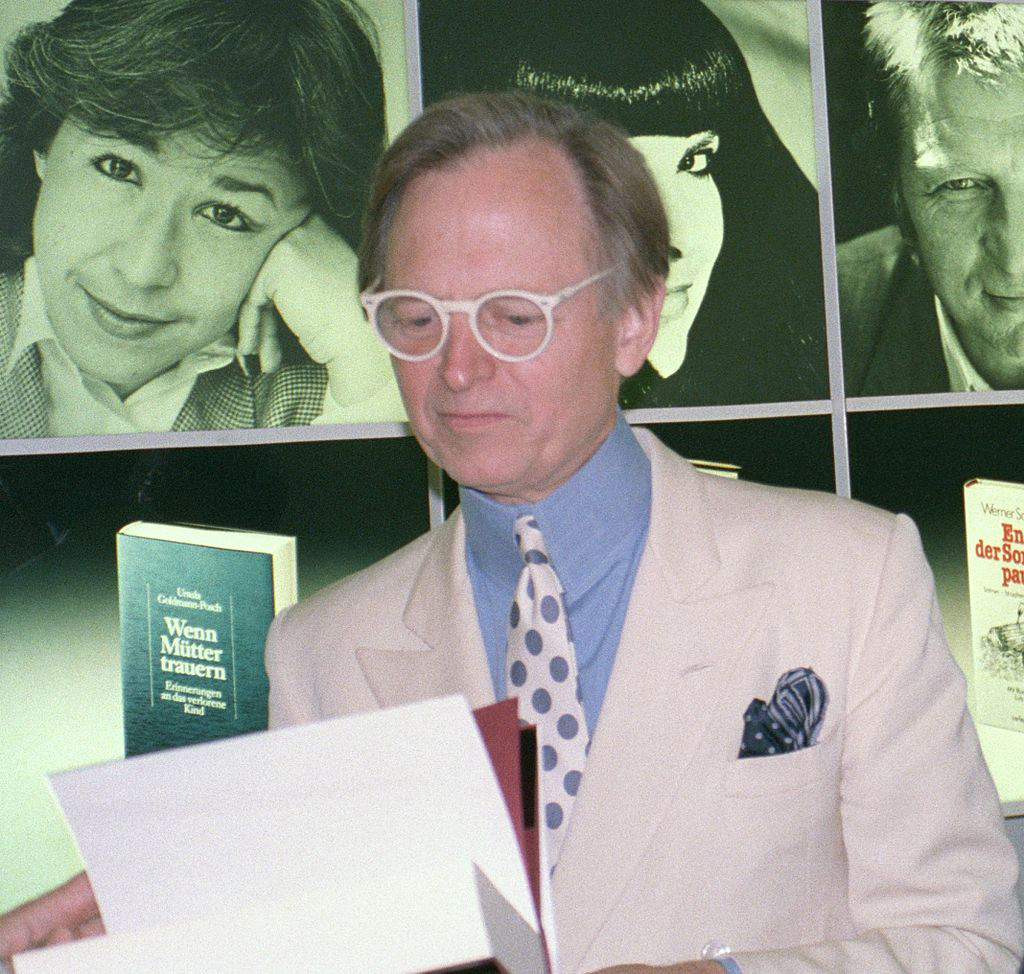

Tom Wolfe.

VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Tom Wolfe, the prolific journalist and novelist who helped foment the New Journalism movement, died last month at 88. Many of Wolfe’s wide-ranging pieces have become standards in journalism classes for the inventive way he combined in them the style and structure of fiction with meticulous and thorough reporting, whether following Ken Kesey and his band of LSD-tripping Merry Pranksters on their drug-laden travails in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968) or venturing into the subculture of custom cars in The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby (1965).

In 1975, Wolfe wrote The Painted Word, an incisive critique of contemporary art, and the world that surrounds it, which he lambasted for being too heavily dependent on verbiage, particularly the writings of figures like Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, and Leo Steinberg—all of whom at one point contributed to these pages. Like much of what Wolfe wrote—and said—it generated no small amount of controversy, and in the September 1975 issue of ARTnews Judith Goldman argued that he missed the mark in examining various problems that exist in the art world. But such criticism aside, the book remains a pillar of postwar art criticism, and one might say that he presciently identified the International Art English that plagues so much writing about art today. —Maximilíano Durón

“Who’s afraid of Tom Wolfe?”

“Who’s afraid of Tom Wolfe?”

By Judith Goldman

September 1975

Is there anything on that blank canvas but blankness?

Tom Wolfe goes nowhere in The Painted Word (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $5.95) he hasn’t gone before. He tells the familiar story that earned him his reputation and made him big at the media box office: the tale of the aspiring haute bourgeoisie. With a nasty humor that conceals his Middle American morality, Wolfe dissects the trappings of the art world to make the old point that “the arts have always been a doorway into Society,” and goes on to present a theory he mistakenly believes anew: “Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.” To understand modern art, one must know the words of current criticism; this is Wolfe’s seeming point.

But Wolfe has not written about the problems in the art world or the crisis in current criticism. He has not written about modern art at all. Instead, he has written a polemic against it, and throughout the essay he makes his dislike of abstract art perfectly clear. He describes the work of Fernand Léger and Henry Moore as a “Cubist horse strangling on a banana,” the work of Morris Louis as “rows of rather watery-looking stripes.” He dismisses Barnett Newman with mock seriousness: “He spent the last twenty-two years of his life studying the problems (if any) of dealing with big areas of color divided by stripes . . . on a flat picture plane.” The parenthetical “if any” encapsulates the animosity Wolfe feels toward modern art; and this is the real message of The Painted Word.

Wolfe’s art world, like all the places he writes about, is social. It is a small, insular place in which bohemia (the artists) and le monde (collectors and trustees) share a mutual goal—to be different, to separate themselves from the bourgeoisie. This old observation has been said better, but seldom with Wolfe’s smug anger. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “Everyone thinks they’re apart from the milieu,” he left affectation the bare dignity of its need. But Wolfe is a cut-rate Prouste who snips together a makeshift cultural history that reverberates with the sound of gossip. The extraneous information sounds too knowing to be wrong. Picasso was a great “boho” according to Wolfe, and Pollock could never make it out of the “boho dance” to join forces with and be celebrated by le monde. How, one wonders, did Wolfe miss Picasso’s famous line, “I want to live like a poor man with money.”

Wolfe’s sociology is easy, fast and inaccurate. He sets sociological subjects up only to put them down, and often his language implies the subject’s fate, a moralistic fate determined by Wolfe. He designates artists “bohos,” which he defines as “twentieth-century slang for bohemian; obverse of hobo.” This denigrating transposition is a sly play on SoHo, an area where artists live. A hobo, whose ragged clothes are real, is a boho’s polar opposite, and if a boho fails, his fate is to become a hobo—or a bum. Supporters of the arts are termed “culturati”; the Latin plural sounds cold, scientific and inhuman. Again, contempt is in the word. Those interested in culture are strange specimens; their behavior is of interest, if distance is kept.

Precious categorizing, name- and label-dropping are Wolfe’s specialty; a gymnast with language, he can make the P in Pucci dizzy with parody and pretense. But art writing is not a comedy of manners, and Wolfe’s coined phrases and choices of words reveal the dark message that betrays the light touch of his pop prose. Angry metaphors—images of war and espionage—describe the making of art theory. Greenberg, he says, “Put over flatness” with Pollock’s success. Wolfe describes Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s reaction to Abstract Expressionism as “zapping the old bastards,” and Greenberg’s and Rosenberg’s reaction to Pop art as “a grave tactical error.” He sees Leo Steinberg as a warrior who gives “the coup de grâce to Clement Greenberg.” “Cheating,” “double-tracking” and “double-dealing” are other words Wolfe favors to describe the making of art and art theory.

Wolfe’s language is revealing. His frenzied prose is effective. Repetition, assonance and alliteration impel language into generalized meaning. The specific is not heard, only a sound—and the sound of The Painted Word combines the tones of propaganda with the promises of religious conversion. To make his case that modern art is completely literary, he presents an argument based on fear, on the premise that what you don’t know can hurt you. Like the audience, Wolfe is bewildered by modern art. “All these years I, like so many others,” Wolfe writes, “had stood in front of a thousand, two thousand, God-knows-how-many thousand Pollocks, de Koonings, Newmans, Nolands, Rothkos . . . waiting, waiting forever for . . . it . . . for it to come into focus, namely, the visual reward (for so much effort) which must be there . . . waiting for something to radiate directly from the paintings. . . .” Wolfe repeats words and stretches out sentences until they engulf the reader. His wait for enlightenment is interminable. And as he waits, the reader waits, feeling the writer’s dilemma, the unbearable angst fo being a philistine, of having tried and failed. The craft of the language might earn a certain respect if Wolfe had succeeded in being either satiric or enlightening. But the message delivered is at best prosaic. Look, he says into the darkness of the readers’ world, you were right all along; you are not missing anything. There is nothing on that blank canvas but blankness.

Ironically, it is what Wolfe does with language that belies his humor and gives him away. He might have kept his guise as the brilliant social critic had he confined his writing to parlor antics, for most of us did not attend the radically chic parties Wolfe wrote about in the ’60s. We entered those living rooms through Wolfe, and his knowing commentary seemed convincing. Wolfe made a mistake in analyzing art theory instead of life styles, for the writings of the art critics he maligns are all in the library. And a reading of Wolfe’s original sources reveals more than his dislike for art; it shows the duplicity of his working method.

To prove modern art fraudulent, Wolfe presents a compendium of misquotations from the writings of three critics: Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg and Leo Steinberg. These are three wise men in Wolfe’s art world who, according to Wolfe, spin a continuum of alchemy that becomes modern art; they write critical theory that influences and even creates painters.

Wolfe groups critics as he did artists and collectors, inventing an imaginary home for Greenberg, Rosenberg and Steinberg which he calls “Cultureburg.” That is Wolfe’s most devastating designation. His three critics lend words of explication that give art its value in the marketplace and for the bourgeoisie. While it may not be anti-Semitic, Wolfe’s message is anti-culture. To Wolfe, high culture is different and dangerous. And although he might explain “Cultureburg” as assonance, the image evoked is of a closed place, a ghetto of sorts, that even the press cannot penetrate. Wolfe has said that “the whole intellectual atmosphere of art is based on mindless faith.” That faith is directed by men in “Cultureburg.” In the heartlands, where they have never heard of assonance, Wolfe’s sentiments will be well received.

As a reader and reporter of art theory, Wolfe adopts the role of the innocent who can see simple truth. Because he is not an art historian, Wolfe presents his inaccuracies as the artless “Gee Whiz” mistakes of an outsider. But Wolfe’s innocence is only a guise for ridicule; he is a professional writer who works the language like plastic, and when he misquotes, it is hardly ingenuous. It is considered a set-up. “I’ve found a new world that’s flatter,” Wolfe has Steinberg say. The quote marks intentionally mislead, because Steinberg never wrote or spoke those words. The quote marks only mean that this what Wolfe imagined Steinberg saying. Another manufactured statement attributed to Steinberg is: “Whatever else it may be, all great art is about art.” What Steinberg wrote was: “All important art, at least since the Trecento, is preoccupied with self-criticism. Whatever else it may be about, all art is about art. All original art searches its limits. . . .” Wolfe presents a fragment, stripped of its context, and makes it sound simple-minded. He even adds the qualifier “great.” Pure fantasy follows. The line, “all great art is about art,” Wolfe maintains, vanquished all the art theory which preceded it. However, the line did not exist until it came out of Wolfe’s typewriter, divorced from its original meaning. Isn’t the intent of this fragment to show how dimwitted art criticism is? Time and again, Wolfe’s free hand with quotations results in a general indictment of modern art and its theory. Another egregious example of Wolfe’s technique is the implied attribution of the question “Can a spaceship penetrate a de Kooning?” to Steinberg. Again, the phrase is Wolfe’s, and it is derived from a reference Steinberg made not to de Kooning but to Jules Olitski and modern space. This is hardly a misunderstanding or good clean fun or trenchant satire; this is, I suspect, dishonest journalism.

Wolfe has not misunderstood recent art theory since he never intended to get it right. Because he reduces concepts to absurdly simple forms, he is understandably attracted to statements which explain complicated or unknown situations and are, therefore, compressed to read with maximum clarity. Two statements that earn Wolfe’s contempt are Greenberg’s “All profoundly original art looks ugly at first” and Steinberg’s “Modern art always projects itself into a twilight zone where no values are fixed.” These lines are props in The Painted Word’s imaginary battle of art critics. Again, Wolfe pulls phrases out of context. Only this time, he juxtaposes them to imply a direct relationship between them. Earlier, misunderstanding Greenberg, Wolfe ridiculed his blunt way of saying that original art is different and necessitates a new way of seeing. Now, he inserts Steinberg, who, according to Wolfe, urbanely polishes Greenberg’s statement and makes it “seem deeper (and a bit more refined).” The conspiratorial tone of an internecine critical camp is of Wolfe’s own making. It is his polemic device to imply that art writing is trickery.

Modern art is unchartable, risky to make and hard to look at. That is why it produces anxiety. But the ultimate value of today’s art is a decision of the future. Art is antithetical to Wolfe’s view of the world. Artists invent a new order. Wolfe works from a sense of past order. He cannot understand “twilight zones where no values are fixed” because his talent as a journalist is as a professional categorizer. He fixes values and puts things in places of his own making. Wolfe’s perspective is the way things were and that, he continually tells us, is the way they should be. Wolfe cannot understand modern art or the men who write about it. His only access to current art is a bare comprehension of its social role. Unfortunately, Wolfe the social critic is as didactic and fearful as Wolfe the art critic.

In the 1960s, when style was the order of the day, Wolfe was considered entertaining. There was enough noise to drown out the moral tone that sped, like a posse, through his words and plots. He had an ear for the noise in New York parlors. And, in a fast phrase, he could cut down an ash blonde socialite or a Yale man on leave from his life. Wolfe’s stories exposed deceptions and focused specifically on social lies. They began or took place at parties and led to similar denouements. Throughout the 1960s, Wolfe found countless ways to spread his dictum of “Know Thy Place.” The social life of the art world and radical politics are ripe subjects for satire; but Wolfe’s satiric attempts often fail by degenerating into mean moralism. His journalistic role is as the outsider. He is the only guest at the party with a notebook, and he brings along the spleen of the uninvited. When he leaves, the world that he visits are in tatters. Wolfe seldom allows his subjects their errant ways. Instead, they are punished in frozen epilogues. The Sculls are left staring into the “galactal Tastee-Freeze darkness of Queens,” and Leonard Bernstein is haunted by “a damnable Negro by the piano.” Wolfe’s articles generally close with the dark night of somebody’s soul.

In The Painted Word, the same hunt persists for a crack in the facade that will expose the suspected hypocrisy. Only, the search is for the flaw in the word. The battleground again is the social arena. The analogue for art is social climbing, and the pretenses Wolfe strips bare are words. The flaw in the words proves the fraud of modern art.

Although Wolfe went to great lengths to build his case against modern art, the message of The Painted Word is not about art, but Wolfe’s familiar one against change, movement and all things different or unknown. To call Wolfe a philistine is to miss the point. He is neither an alien nor an unsophisticated man, but a reactionary who is for the status quo, deeply suspicious of radicals, black or white; intellectuals; art; and high culture. Difference is dangerous in the heartlands. And Wolfe, as the protector of Middle American values, writes for those folks back home. He brings light to their darkness and by, telling them about the moral shams that pass for big time in art and politics, he confirms their fear and prejudice. Culture, like the big city, is wicked and dangerous—at least according to Wolfe.

The sad postscript to The Painted Word was the art world’s reaction. Who’s afraid of Tom Wolfe? Many people seemed to be and grew serious and defensive. Art seldom receives the attention of journalists or the popular press and Wolfe’s image of it makes the neglect seem justified. But the less public reason for the defensiveness has to do with conditions inside the art world. Much current art writing lacks either passion or conviction. But the fault does not lie with Greenberg, Rosenberg or Steinberg, for they are passionate observers of the art scene. Not one of them has responded to Wolfe. At least they knew he was not writing about art.

[ad_2]

Source link