[ad_1]

Civilizations host Simon Schama outside Itimad-Ud-Daulah’s Tomb, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India, commissioned by Nur Jahan and completed in 1628.

COURTESY NUTOPIA LTD AND PBS

Civilizations

Civilizations, a world-, time-, and idea-encompassing nine-episode series, narrated by actor Liev Schreiber, might surprise many viewers by suggesting they owe gratitude to history’s looters and marauders. In the war-torn quarters of the world, such villains may have inadvertently perpetrated acts of preservation when not engaging in devastation, it argues. They steal and sequester artistic treasures, all in the name of religion, politics, or self-interest, but in so doing they keep them out of harm’s way (albeit harm often of their own creation).

Such conundrums are the stuff of this beautifully photographed, well-researched, and often thought-provoking trip through art and cultural history. The BBC series, which airs on PBS on Tuesdays (the fifth episode premieres May 15, with another batch of five starting June 12), follows late on the heels of Sir Kenneth Clarke’s venerable, albeit stuffier, 1969 series Civilisation. Clark’s title, absent the pluralizing s, is indicative of the parochialism of its time—pre-global and pre-multicultural.

Civilizations by contrast, led by the well-known art historian Simon Schama, takes us on an illuminating, often blustery ride from pre-civilization to present—not-yet-post—civilization. “Historically, my view is close to Clark’s,” Schama said. “What’s different here is that Clark was consumed by the classical position. You couldn’t do Asian art then”—not ceramics and mud, for example. Here, Schama and company could do things like “explore in depth Chinese landscape paintings and explore connections” with other cultural material in ways you couldn’t do even in such great institutions as the Metropolitan Museum, which “have their own domains.” On the show, Schama also speaks to the ironies of history with the recent destruction by ISIS of ancient art in Mosul. He relates the story of Khaled al-Asaad, the scholar who refused to lead raiders to the city’s treasures, which had been hidden to protect them. In return for his valor, he got his head chopped off.

Presenter David Olusoga with various Benin Bronzes, Unknown Artist (ca. 1550 – 1650), British Museum, London, in Civilizations.

COURTESY NUTOPIA LTD AND PBS

Other episodes are presided over by the provocative classicist Mary Beard and the Anglo Nigerian scholar David Olusoga. Overall, it’s a selective history, missing some landmarks such as the Sistine Chapel (to which Eric Gibson objects in the Wall Street Journal) and artists like Jan van Eyck, as Sebastian Smee laments in the Washington Post), but choices had to be made in service to storytelling and point of view. In other words, had they but time enough and space . . . Modern in its focus on artifacts and attitudes, the tale begins some 70,000 years ago, as presented by Schama in the first episode, “The Second Moment of Creation.”

There are the abstract scratchings on stones, and, on the walls of the caves of Monte Castille in Spain—tiny red dots and red hands composed with vegetable dyes, markings on abalone shell with manmade pigment, as well as etched symbols on a slab of red ocher pointing to what Schama calls a “cognitive revolution.”

From here, it’s on to Lion Man, a precociously realistic prehistoric sculpture carved from elephant ivory, and then the Buddhist caves of Ajanta in India, the Mosques of Istanbul, the cities of Mesoamerica, Chinese burial figures, and early landscape painting. One surprise is learning of the relationship between painting and sound in European caves. Artists, it is suggested, were drawn to the caves based on sounds. It’s a long speedy trip.

Dome inside the Suleymaniye Mosque (1550-1557) Sponsored by Sultan Suleyman – Instanbul, Turkey, in Civilzations.

COURTESY NUTOPIA LTD AND PBS

Mary Beard’s domain is slightly hipper, addressing anthropology and religion and controversial social issues. Her episode “How Do We Look?” comes closest to a direct critique of Clark. It focuses on the art of the ancient world, beginning with Olmec heads in Mexico, through Pharaonic figures in Egypt, terracotta warriors in China, and ancient Greco Roman statues.

Beard refers to Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the 18th-century writer, who, she says, elevated the statue “above a mere artwork,” explaining, “You could track the history, the rise and fall of civilization, through the rise and fall of the representation of the human body.”

Then, in an episode titled “God and Art,” she poses a crucial question in the cultural divide: “Is the art in service to the divine, or is it the art that itself is being worshipped?” Therein lies a fundamental question in what she considers this “grand gesture of multicultural understanding”—the problem of idolatry. Iconoclasm versus idolatry.

Beard points to how a Muslim mosque was built with smashed objects from Hindu culture and talks about contemporary art using typewriter keys in a sculpture—symbols that only have meaning in their original contexts.

It’s the unexpected details in the series that capture our attention and imagination. In the fascinating episode “Encounters,” we reckon with the idea that Lisbon was at the center of the first stage of globalization, as Olusoga observers. With expanded travel possibilities in the late 15th century, Portuguese traders brought new products to Japan as well as to Holland, Benin, and Central America.

Walled City of Lahore, Pakistan, rebuilt by Emperor Akbar, 16th Century, in Civilizations.

COURTESY NUTOPIA LTD AND PBS

The Shogunate, however, closed off Japanese culture from outsiders for two centuries, between 1600 and 1828, but Dutch traders were not banned, so among the products introduced to Holland were Dutch glasses, convex lenses, and stereoscopes.

The products included Benin bronzes and other African sculptures. There was an ensuing boom in sculpting and casting. Africans constituted one in ten of Lisbon’s population, and they were represented at every social level, which is evident in the paintings of the period. There were white as well as black slaves, Olusoga notes.

Such exchanges abound in these episodes. In a discussion of color, Schama speaks of how Japan’s desire to make life in cities bearable in the 18th and 19th centuries led to a demand for “cheap, mass-produced woodblock prints suffused with dazzling color.” These prints, by artists such as Hokusai, influenced the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Schama ends the episode in Matisse’s chapel in Vence, “where color is used,” he says,“ against a backdrop of the Second World War—once more to enrapture, enlighten, and as a path to God.”

The series includes many other experts, such as the illuminating Harvard historian Maya Jasanoff, as well as contemporary artists, including such international figures as Michal Rovner, Cai-Guo Qiang, and Kara Walker. They pull many of the arguments into the present. Today, with all our available media, we may find ourselves overly familiar with the present and far more excited by the findings of the past. But that will always change.

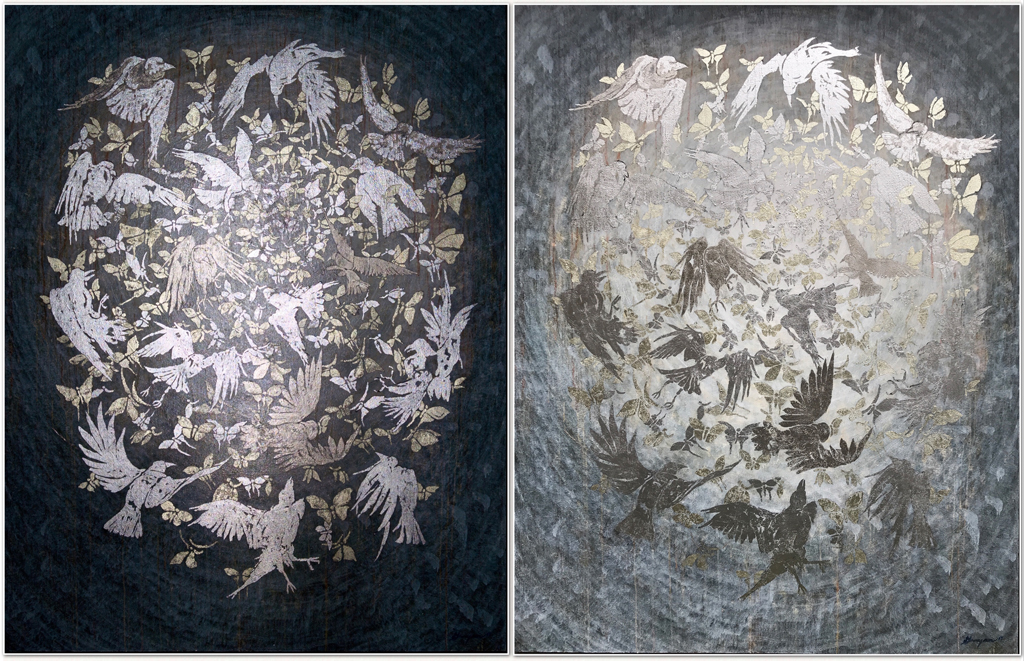

Neil Grayson, 16 Birds (Industrial Melanism), 2017, silver, palladium, white gold, and oil on canvas, two views of the same canvas under different lighting—night and daylight.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Neil Grayson’s Many Metamorphoses

Alchemy assumes many guises, real and imaginary, its reach extending from chemistry to magic. It can turn pleasure into sorrow, light into dark, stillness into motion. In Neil Grayson’s elusive works, it touches on nothing less than the genetic, the material, the poetic, the spiritual, the psychological, and the metaphoric. A founder of the Dactyl Foundation, based in New York and devoted to art and science research, Grayson purveys the deep and infinite realm of interconnectedness.

Since being established in 1997, by Grayson and novelist/philosopher of science V.N. Alexander, Dactyl has hosted poets, writers, and artists ranging from Robert Motherwell to John Ashbery to Elizabeth Hardwick, and sponsored conferences and events in New York and beyond, such as its “Biosemiotics Gathering” to be held in June, in Berkeley, California.

Neil Grayson, Reinvented (Industrial Melanism), 2015, silver, white gold, and oil and canvas.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Testifying to the foundation’s aspiration was Grayson’s recent show of paintings, titled “Industrial Melanism,” at Eykyn Maclean Gallery, which was strikingly devoted to unearthing the complexities of art and science. Grayson said he is devoted to “poetics and structure—to maintaining the balance.” The ambiguity of tone in his painting and the inherent darkness and light at play in his imagery show and question the way we see and what we see.

Masses of shimmering silver lepidopterans that vary their individual and collective shape and substance depending on the angles from which they are viewed appear to be in continual motion as light glints off their surfaces; as a body, they shift into formations and then partially fade from view. Grayson’s inspiration is the peppered moth, a species that changes in color from white with speckles to pure black. He said he was motivated to make his work by studying the phenomenon of Industrial Melanism, a process whereby the skin or fur covering a living organism blends in with the environmental soot produced by industry. And “the melanization of a population,” he explained, “increases the probability that its members will survive and reproduce.” The presumption is that the evolution that takes place over generations favors the darker animals, which, being less conspicuous to predators, are better able to prevail.

Grayson began his investigation by hand when he was 16 years old, spending many hours at the Metropolitan Museum. He would painstakingly copy the techniques of the Old Masters—especially Rembrandt, and, as he closely examined the self-portraits, Grayson found himself exploring how light illuminates darkness. In fact, he is profoundly motivated by such polarities across the board. Drawn to darkness, he remarked, “I love the Hopeful Monster theory as well as Breaking Bad, in which the character who inevitably becomes what he/she was meant to be—bad? good?—reached that point where they discover their language.” Nevertheless, he pointed out, “the challenge with darkness is that you find something unique in it without necessarily becoming negative.” He admits to being an inveterate optimist.

There could be many expressions of the effects of alchemy—in literature, for example. In a short story written in 1908 by the American writer H. P. Lovecraft, titled “The Alchemist,” the author sums up his state of mind: “I was isolated, and thrown upon my own resources, I spent the hours of my childhood in poring over the ancient tomes that filled the shadow-haunted library of the chateau, and in roaming without aim or purpose through the perpetual dusk of the spectral wood that clothes the side of the hill near its foot. It was perhaps an effect of such surroundings that my mind early acquired a shade of melancholy. Those studies and pursuits which partake of the dark and occult in Nature most strongly claimed my attention.”

The proof, for Grayson, turns out to be in his life, where art and reality intertwine. Grayson’s highly sensitive 13-year-old son Maddox, whom he home-schools, did not fit into any conventional school, but he spontaneously emerged from his chrysalis like a liberated moth as he sat at his computer and taught himself to write and mix music. He did this without having played any instrument and without knowing how to read music. Miraculously, however, he has ended up with a career, working under the guidance of his multi-Grammy-winning mentor, producer Mike Dean, composing for and working with noted hip-hop artists. He broke out of his isolation and emerged, thanks to alchemy and nature, and talent, a fully engaged teenager.

In Grayson’s haunting works, we see the forces of nature mimicked in human, plant, and animal life. Recently, Grayson said, he has been consumed by the idea of replicating the malleable shades of the peppered moth in metals layered in oil and pigment, magically uniting substance and light.

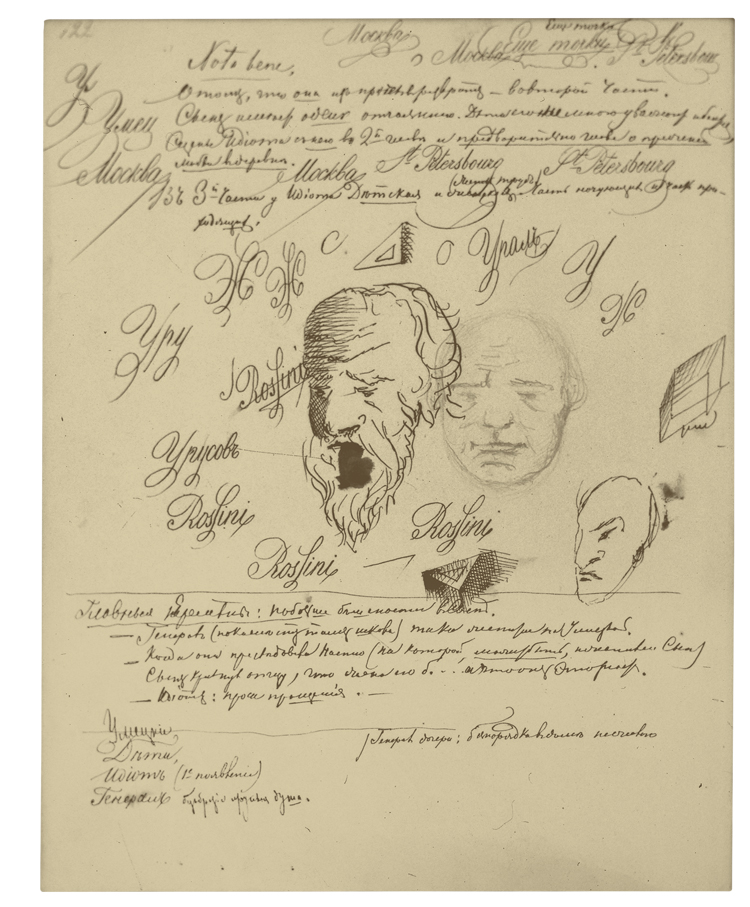

An illustrated manuscript page by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

LEMMA PRESS

Dostoevsky as Draftsman

Konstantin Barsht

The Drawings and Calligraphy of Fyodor Dostoevsky: From image to word

Translated by Stephen Charles Frauzel, 468pp. Lemma Press. €150.

Dostoevsky’s “handfulness” clearly supplements his “mindfulness,” as this huge, information—packed and insightful tome reveals. Konstantin Barsht, a researcher at the Russian Academy’s Institute for Russian Literature (Pushkin House) in St. Petersburg, argues that Dostoevsky’s drawings and doodlings are essentially “notes to himself” more than actual works of art. But we do learn that the novelist did indeed appreciate art and studied art history.

As a youth he attended a military academy that demanded proficiency in drawing and geometry as much as in traditional academic studies. Dostoevsky did not excel initially in drawing or calligraphy. However, to raise his grades and to satisfy his very demanding father, he worked hard to succeed and even excel. But he was not a practicing artist.

In 1921, 30 years after Dostoevsky’s death, researchers discovered his notebooks and drawings. Editor Stefano Aloe writes of his portraits in the introduction to the book: “[Dostoevsky] was mainly concerned with grimaces and physiological features of facial composition that expressed a character’s idea.” He would also signal “ ‘psychological points’ of the storyline by depicting isometric prisms” when he was working on The Idiot.

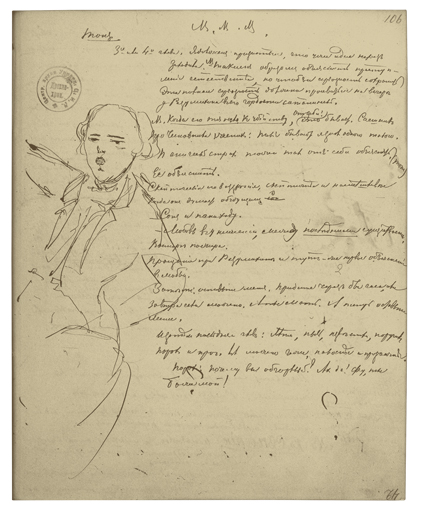

An illustrated manuscript page by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

LEMMA PRESS

Included in the book are chapters on historical figures and on his fictional characters. He depicts Cervantes, Barsht writes, as “a person who seemed to be completely immersed in himself, absorbed by his contemplations, pondering his destiny—the destiny of the Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance.”

There are sections on Peter the Great, Madame de Staël, and the critic Vissarion Belinsky, as well as Dostoevsky’s self-portrait, among many, grouped together as “Familiar Faces.”

In the introduction, Aloe divides Dostoevsky’s work into specific images (portraits—the idea of characters) versus symbols (architecture—and decorative patterns). The author was a consummate calligrapher, as the pages covered with writing in different styles and with different implements attest—he was eloquently described as “a calligraphic aesthete.” He loved materials, and used nut ink primarily.

“Calligraphic self-reflection stands in juxtaposition to the writer’s rapid cursive, which appears laconic and placid, but at the same time is full of dynamic urgency,” Aloe[?] writes.

As a young man Dostoevsky was sent to board at the Military Engineering Academy. His drawings were always defined by line and shading, which made the images look very theatrical.

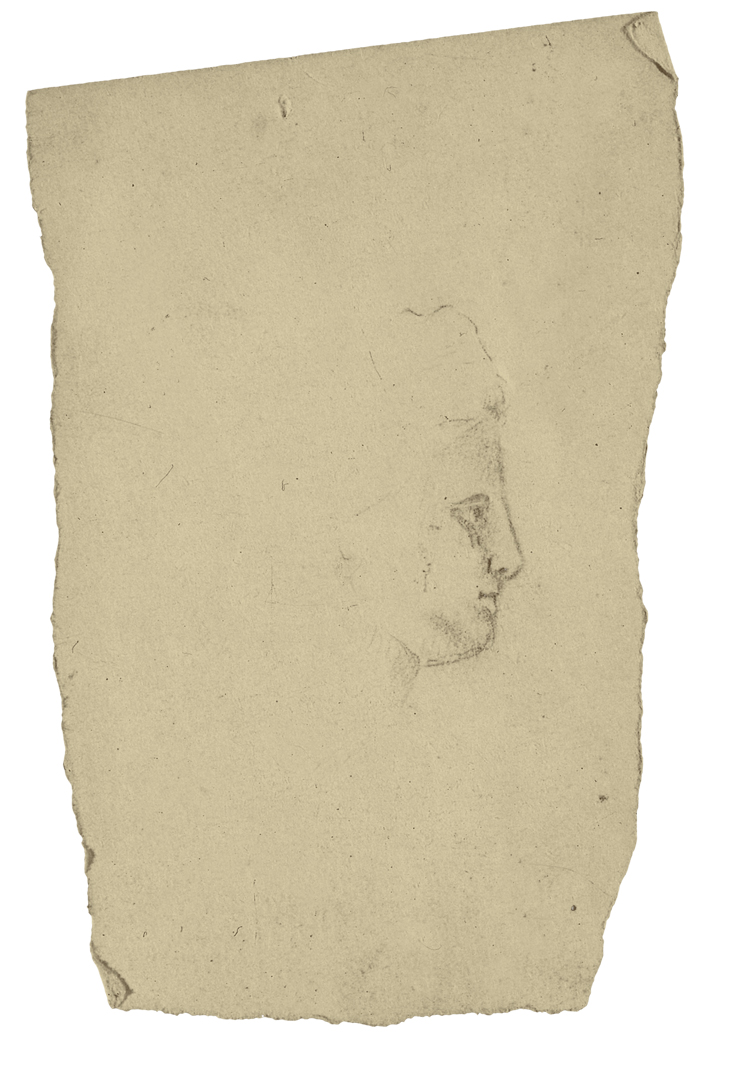

An illustrated manuscript page by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

LEMMA PRESS

They also revealed his psychological states, Aloe argues. “In pen drawings, as in the process of writing, the nature, pace and tempo of arm movement” can directly express an author’s emotional state at a given moment. “The lines that make up a drawing reveal the pulse of inner life, the beating of thoughts and feelings of the person who inscribes and draws it.”

According to the press release, Dostoevsky’s notes to himself “represent that key moment when the accumulated proto-novel crystallized into a text. Like many of us, Dostoevsky doodled hardest when the words came slowest.” Some of the writer’s character descriptions, Barsht argues, “are actually the descriptions of doodled portraits he kept reworking until they were right.” He combines the human, the architectural, and the calligraphic, “apparently the three main avenues through which Dostoevsky pursued the doodler’s art.”

The wonder of these drawings lies not in their beauty or perfection, but rather in their serious investigation and documentation of Dostoevsky’s thinking and writing process, as well as his identification with his subjects. This book is a massive enterprise that requires close attention and an eagerness to assume a position in this author’s ingenious mind.

[ad_2]

Source link