[ad_1]

Chaim Soutine, Still Life with Rayfish, ca. 1924, oil on canvas.

©ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/IMAGE: METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART AND ART RESOURCE, NEW YORK/METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, THE MR. AND MRS. KLAUS G. PERIS COLLECTION, 1997 (1997.149.1)

Chaim Soutine occupies a strange position within the history of modernism. Having been immediately hailed by European critics as one of his era’s greatest painters, Soutine, who was based in France for much of his career, was largely ignored in America until the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted a small exhibition of his work in 1950. Soutine’s thickly painted canvases, which often harness the physical properties of his medium to depict carnage and meat, are currently on view at the Jewish Museum in New York, in a survey aptly titled “Flesh.” With that show in mind, republished below is the artist Jack Tworkov’s essay on Soutine’s MoMA retrospective, originally in the November 1950 issue of ARTnews. In the review, Tworkov discusses Soutine’s strange reputation, noting that “he had practically no influence on American painting,” and addresses the painter’s formal concerns. —Alex Greenberger

“The wandering Soutine”

By Jack Tworkov

November 1950

Analyzing the tragedy of the deracinated artist, his new retrospective at the Modern Museum is reviewed here by a distinguished U.S. painter

“The ancient world takes its stand upon the drama of the universe, the modern world upon the inward drama of the soul.” —Whitehead

Cézanne appears as an expressionist at the beginning and again at the end of his career. But that career as a whole is well defined by a reference to Classicism as an art which “takes its stand upon the drama of the universe.” At the opposite pole is Soutine, representing the “inward drama of the soul.” The art of Cézanne represented the intensity of objects that endure forever like mountains . . . his personal anxiety coming through as the fire within the mountain. His method of a linked organization of non-figurative pieces expressing themselves as objects suggests atomic structure. Soutine’s art refers to the drama of individual blocks of Cézanne art, putting flesh on his bone. Cézanne’s art is essentially spatial. Soutine’s, an art of movement, has temporal overtones. Their sharp polarities illuminate each other. We vacillate between these poles, suffering alternately from wounded fascination or revulsion.

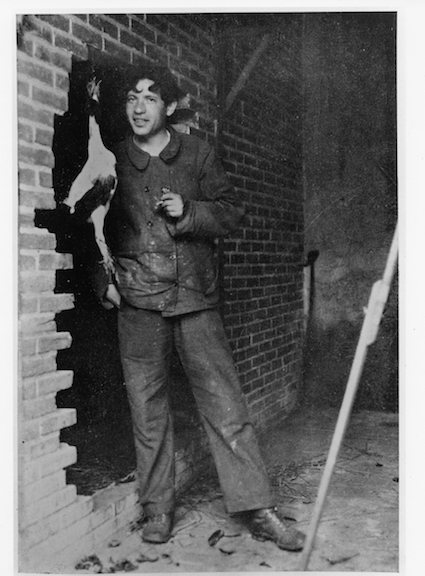

Soutine with a chicken, hanging in front of a broken brick wall, Le Blanc, western France (Indre), 1927.

THE KLUVER/MARTIN ARCHIVE

Their biographies hint at similar contrasts. I envy Cézanne living out his manhood in the same village where he was born. If in his childhood the shadowy places plagued him with grotesque and torturing shapes, I imagine in later life he inspected all such locales in clear light. I am sorry for Soutine living in a foreign land. He could never exorcise the terrors of his childhood, and so they possessed him all his life.

The exhibition of eight pictures by Soutine opening at New York’s Museum of Modern Art [to Jan. 6] will, for many people, be the first real encounter with his work and for nearly everyone will provide the first opportunity for a comprehensive view.

Born in the multitudinous household of a poverty-stricken Jewish tailor, the journey he made when he was nineteen, from the mediaeval Lithuanian ghetto village to Paris, has to be measured not only in hundreds of miles but also in hundreds of years. It is not the same as going from Amsterdam, London or New York to Paris. It indicates an extraordinary character—restless, audacious and imaginative. An enormous and unrelieved strain must have been set up when his inherited Jewishness, containing elements of squalor, mustiness and warmth as well as elements of religious and moral grain, confronted the brightness, the gaiety, the carefree atmosphere of the Western capital. But however eager he had been to abandon his background, the unrestrained libertinism of his new situation must surely have haunted him with the idea that, perhaps, his life now lacked roots in any valid order. For the problem of assimilation of a new environment is not only what you can adopt but also what will adopt you.

What came to his rescue was that the new environment was full of spiritual refugees, intellectuals who, regardless of origin, felt homeless. And it explains why Soutine’s work, in some ways, the most revolutionary and shocking of its day, found, nevertheless, an immediate and rather wide audience throughout Europe. For it reflected the upheaval of our time: the brutality and pity, disquietude and religious quests, alternating despairs and frantic jubilations. Nevertheless, Soutine’s posture before the world, revealed in his painting, is anything but pathetic; on the contrary, it is passionate, arrogant and cocksure.

It is well to remember that had he lived he would be only fifty-six years old today. It is so easy to assign him to an earlier generation. With the exception of the influence Soutine had on a few social-conscious painters of the late ’thirties, who had a short view of him as primarily a social satirist, he had practically no influence on American painting. If you consider that every major European painter contributed to the American development, is it not astonishing that the advanced artists here were almost completely oblivious to him? The decisive influences in that quarter were exerted by Duchamp, Klee, Kandinsky, Miró, Arp, Masson and Mondrian. Undoubtedly they represented the most civilized, polished and sophisticated taste in Europe, and they continued the stream of innovation that began with cubism. And yet, with the exception of Duchamp and of Mondrian (about whom I hesitate, for he is a special case), the remainder strike me as of a lesser magnitude compared to Soutine.

Chaim Soutine, Chicken Hung Before a Brick Wall, 1925, oil on canvas.

©ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/KUSTMUSEUM BERN, SWITZERLAND

The lack of interest in Soutine here may be found in the circumstance that our artists, over-burdened with a too-conscious search for a clean departure from the past, were too much impressed with innovations that lent themselves clearly to logical analysis and reconstruction. Whereas, on the surfaces, Soutine is not only too traditional in outlook, but he technically defies analysis of how to do it. But it is precisely this impenetrability to logical analysis as far as his method is concerned, that quality of the surface which appears as if it had happened rather than was “made,” which unexpectedly reminds us of the most original section of the new painting in this country. Viewed from the standpoint of certain painters, like De Kooning and perhaps Pollock, about whom there is no reason to imagine any real Soutine influence, certain qualities of composition, certain attitudes toward paint which have gained prestige here as the most advanced painting, are expressed in Soutine in unpremeditated form. These can be summarized as: the way his picture moves towards the edge of the canvas in centrifugal waves filling to the brim; his completely impulsive use of pigment as a material, generally thick, slow-flowing, viscous, with a sensual attitude toward it, as if it were the primordial material, with deep and vibratory color; the absence of any effacing of the tracks bearing the imprint of the energy passing over the surface. The combined effect is of a full, packed, dense picture of enormous seriousness and grandeur, lacking all embellishment or any concession to decoration.

Only those whose fastidiousness makes them impervious to any painting which has elements of representation may not see this.

I do not mean to say that Soutine’s painting depends for appreciation on the subsequent development of a certain phase of abstract art. But if one goes as far as to see that these abstract elements have a rich existence in his work, then one can go on to the appreciation of the full Soutine despite any supposition that, by temperament, he probably detested abstraction any form.

It is logical that certain artists should be indifferent to Soutine—artists whose standpoint is that the picture is an object, a system of balances, creating an order which is its own end, without meaning beyond itself. This position concludes that to be fully effective the painter ought to stand beside the architect, the industrial designer and the decorator. It requires for its fulfillment a rich and highly civilized consumer. And except in some foreseeable utopia, such artists ought to accept, like the aristocrats of haute couture, a status as the willing servants of a self-aware haut monde.

Chaim Soutine, Fish, Peppers, Onions, c.a 1919, oil on canvas.

BARNES FOUNDATION, PHILADELPHIA

The case with Soutine is different. He stands with the philosopher and the poet. He represents the deracinated intellectual—the bohemian who rejects membership in any class, especially in the capacity of a servant. He represents the attitude that society is well served when it serves art. Where the artist in the former case has for his aim the improvement of the environment, to make it more efficient, hence, more beautiful, the attitude from Soutine’s side, toward the representative of society, has no aim beyond the engagement of his mind through a sensuous experience. Hence the former’s concern with careful workmanship and precise appearance, and Soutine’s apparent indifference to such problems—an indifference carried at times toward the picture itself, since the artist’s passion is not for the picture as a thing, but for the creative process itself. It negates professionalism.

Soutine’s painting contains the fiercest denial that the picture is an end in itself. Instead it is intended to have a meaning which transcends the dimensions and material. The picture is meant to have impact on the soul and not merely impact on the wall. It is not the habiliment of any one who can afford to pay for it—it is first and foremost the dress for the artist’s thoughts, concepts and emotions. It is classic Western painting, not decoration.

Chaim Soutine, Side of Beef with a Calf’s Head, ca. 1923, oil on canvas.

©ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/IMAGE: RMN-GRAND PALAIS AND ART RESOURCE, NEW YORK/MUSÉE DE L’ORANGERIE, PARIS, COLLECTION OF JEAN WALTER AND PAUL GUILLAUME

Soutine derives an immediate advantage by painting from life; because his motive is settled in advance, he does not have to tease it out in the process of painting. It gives him a sure footing and it sets free his energies for a full and uninterrupted flow into his painting. The composition is not a plan, a previous arrangement into which the objects are squeezed. It is rather the unpremeditated form the picture takes as a result of the struggle to express his motive. But the artist’s attitude toward the commonplace things that fill his picture—people, fowl, landscape—is not a simple one. It assumes that the relation between the subject (the painter) and the object is not fixed, but that the object, the more deeply it is experienced, changes, changing also the attitude of the painter towards the object. And it assumes that this process goes on continually throughout the duration of the creative act. The picture does not refer to the artist at the beginning or at the end of the process, but refers to the whole sequence of relative changes that took place. Hence the fluidity of the image, the unpredictability of its outline, the “shake”: and in a flash it explains why Soutine’s subjects, in spite of violent distortions, have such intense reality.

This struggle on the part of the artist to capture the sequence of ephemeral experience is not only the heart of Soutine’s method, but also expresses his tragic anxiety, his constant brooding over being and not being, over bloom and decay, over life and death. Sometimes it includes in the process a savage flash of humor, as when a dead bird, which in Soutine looks so utterly and irrevocably dead, at the same time manages to look so ridiculously alive.

This method is the result of the most self-abnegating discipline. It requires the unity of instantaneous perceiving and doing—a headlong rush which cannot be retarded for the elaboration of detail. It excludes touching up. If the artist fails the failure is complete and disastrous. When he succeeds it is a miracle. In this process the he hand is the dancer, following the rhythm of the disturbances of the soul. When the soul is dead the hand knows nothing. It is not a technique but a process. It is most unlike carpentry.

[ad_2]

Source link