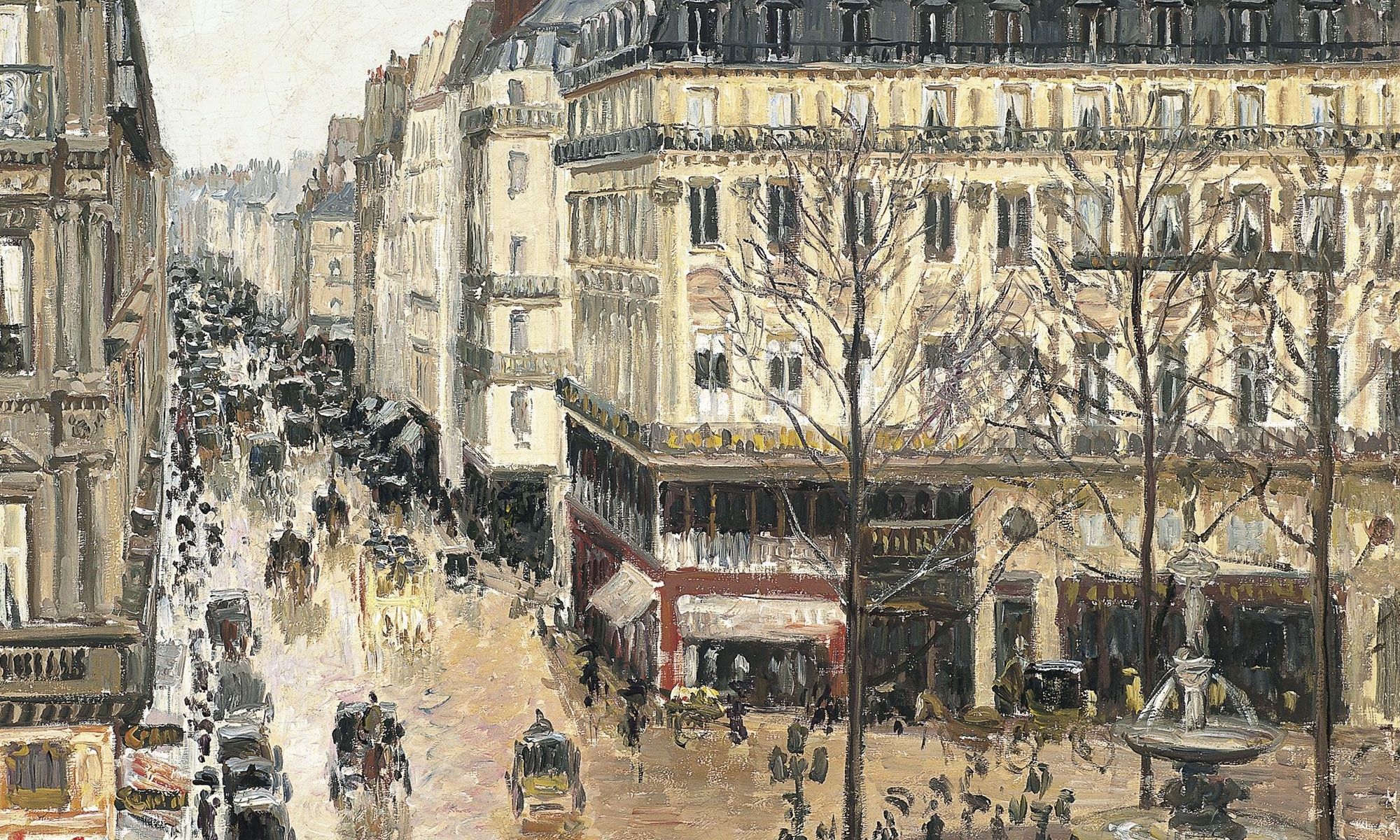

Camille Pissarro, Rue St Honoré, apres-midi, effet de pluie, 1897 Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, via Wikimedia

A new California law is seeking to undo a recent decision by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which seemed to end a lawsuit brought by the heirs of Lilly Cassirer for restitution of a painting stolen from her by Nazis during the Holocaust.

California Governor Gavin Newsom, who signed the law Monday (16 September), said in a statement that the legislation was introduced after the Ninth Circuit decision “allowed a Spanish museum to retain possession of a famous Impressionist masterpiece stolen by the Nazis”. The new statute “mandates that California law must apply in lawsuits involving the theft of art or other personal property looted during the Holocaust or due to other acts of political persecution”. The law took immediate effect, under a California urgency statute provision.

In January, the Ninth Circuit appeals court determined that the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation (TBC), in Madrid, owns Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint Honoré, apres midi, effect de pluie (1897). The decision settled a question that the US Supreme Court had put to the court in 2022 on remand of the case: which state’s substantive law—California’s or Spain’s—applied to the claim for the painting. Under California’s substantive law, a thief cannot pass title to anyone, including a good faith buyer; the plaintiffs would have title to the Pissarro, and TBC would not. But under Spanish law, TBC would hold prescriptive title, because it did not have actual knowledge that the work was stolen when it bought it from Baron Thyssen-Bornemysza, and TBC had possessed the work publicly in good faith for over three years before the plaintiffs brought suit. Looking to the procedural law of California, the Ninth Circuit said that Spain’s substantive law applied.

The new statute seeks to reverse that, saying that the substantive law of California applies in claims for art or personal property taken in cases of political persecution.

“The California legislature and governor Newsom have unequivocally stated that California law requires the return of stolen art to the rightful owners, and that includes art looted in the Holocaust,” David Barrett and Steve Zack, of Boies Schiller Flexner, lawyers for the California-based Cassirer family, tell The Art Newspaper. “The statute applies to the Cassirer case and we will take appropriate steps to bring it before the court.”

Thaddeus Stauber, a lawyer at the US firm Nixon Peabody who represents TBC, declined to comment on the new California law.

In 1939, Lilly Cassirer, based in Berlin and the owner of the Pissarro painting, was forced to sell it to the Nazis to obtain an exit visa, and the payment was deposited into a bank account she was not allowed to access. After various transactions, the painting entered California in 1951, only to leave the state in 1952. It was eventually bought by the baron in 1976 and stayed in Switzerland until he loaned it and his collection to TBC, in 1992. Spain bought the collection in 1993, and since 1992, the painting has been on public display in Madrid at the Villahermosa Palace, which TBC, an instrumentality of Spain, maintains.

The plaintiffs are the heirs of the original plaintiff, Claude Cassirer, Lilly’s sole heir, who died in 2010. One of those heirs, David Cassirer, joined Newsom for a bill signing ceremony at Los Angeles’s Holocaust Museum LA.

The new law says that under California law, a thief cannot convey good title to stolen works of art. It adds that California substantive law will apply, both going forward and to actions where the time to file an appeal has not expired, including petitions for appeal to the US Supreme Court.

In July, the Ninth Circuit denied a request by the plaintiffs for a rehearing. Their likely next move now is a petition in federal court to revive the case.

It is not clear whether the statute will withstand court scrutiny. In 2003, a California law intended to facilitate Holocaust-era insurance claims by California residents was struck down by the Supreme Court, which said it interfered with the president’s conduct of US foreign policy.