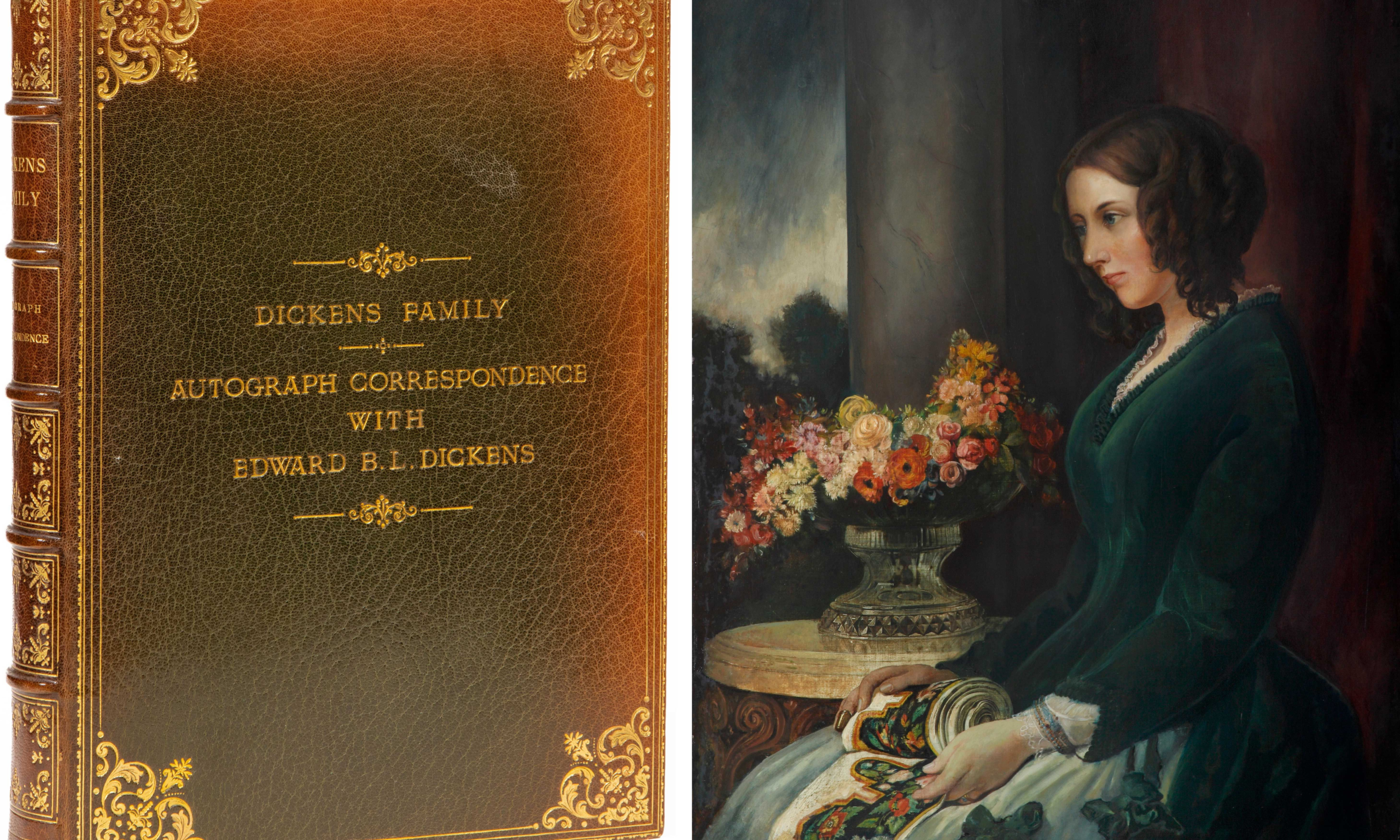

Left: the volume of unpublished letters

Right: Portrait of Catherine Dickens by Daniel Maclise (1847)

Book: Photo: Lewis Bush, courtesy of the Charles Dickens Museum. Portrait: Courtesy of the Charles Dickens Museum

A volume of unpublished letters exchanged between members of Charles Dickens’s family after his death has gone on display in London. The documents, on view at the Charles Dickens Museum in Kings Cross, reveal the enduring love that the author’s wife Catherine—from whom he had brutally separated—had for their children.

Even Dickens’s greatest fans, and many of his friends in life, found it very hard to cope with his treatment of Catherine. They married in 1836 when they were both in their 20s, and as an exhibition dedicated to her at the Dickens Museum in 2016 made clear, she was intelligent, kind, a gifted musician, and devoted to their ten children. She never spoke one harsh word in public about her husband’s treatment.

Dickens, in contrast, dropped any friends who showed any signs of taking her side. He sought to portray her as an unfit mother, and neurotic if not actually mad. He first moved out of their bedroom and had the connecting door boarded shut, and then when he formally separated from her in 1858, published a newspaper advertisement—which friends implored him not to do—announcing that “some domestic trouble of mine of long standing” had been resolved. The secret he was keeping in the shadows was his relationship with the much younger actress Ellen Ternan.

The newly discovered letters, bound into an album which the museum acquired for £5,500 at an auction of the library of William Foyle, founder of the eponymous bookshop, are from Catherine, Dickens’s siblings and aunts to Edward, the youngest of the 10 children. Dickens, who nicknamed him Plorn—or in full Plornishmaroontigoonter—encouraged the boy to emigrate to Australia aged 16. Plorn was never particularly successful and died there aged 59.

The letters from Catherine destroy Dickens’s claim that Catherine was “a cold and distant mother”. They ache with warmth for her children and longing to see them more often. They also convey hope that in the wake of their father’s death, she may be able to visit them at Gad’s Hill, the home in Kent where all the children except Charles Junior moved out of London with him.

Emma Harper, curator at the museum, says the objects give Catherine a voice: “This fascinating collection destroys the image that Charles Dickens tried to create when he separated from Catherine Dickens in 1858, alleging that she was an unfit wife and mother.”

Much of the correspondence sees the family discussing contemporary news, including the visit of the Shah of Persia, and the trial of the Tichborne Claimant—an Australian butcher who tried to claim an aristocratic fortune in England. One particularly poignant letter, however, explains why Catherine has been out of touch for a period.

On Christmas Eve 1878 she wrote: “I have had a painful and tedious illness and am still obliged to lie almost constantly on my sofa but darling you must not be anxious about me, for thank God, I am slowly improving and my doctor gives me hope that with patience and time I shall be all right again. I must just express my most affectionate good wishes of the season although the New Year will be in some time before you receive this. I cannot tell you the devoted love and kindness I receive from all my dear children in my illness. God bless you my own Plorn.”

Pages from the letter Catherine sent to Plorn on Christmas Eve 1878

Courtesy of the Charles Dickens Museum

Catherine was not “slowly improving”. The “tedious illness” was cancer, and she would be dead within the year, aged just 64. She is buried in Highgate cemetery, far from Charles’s grave in Westminster Abbey.

The letters are on display until November at the museum in Doughty Street, Dickens’s only surviving London home, the setting for the happy early years of their marriage.

A less emotionally freighted relic related to Charles Dickens has returned to the house in where it was made—a four-fold screen decorated by the author and his great friend, the actor William Macready, at Sherborne House in Dorset in the 1850s. The pair used hundreds of prints, scraps and newspaper cuttings, probably as an educational prompt for Macready’s children.

The Macready-Dickens screen, which has been restored, on display at The Shelborne

Photo: Tory McTernan

Dickens was a guest of Macready’s at Sherborne on many occasions. In 1854 he gave a public reading in aid of the Sherborne Literary and Scientific Institution. Initially tickets, at five shillings, sold poorly and Macready raged “A crown, what is it? The cost of a bottle of bad wine swallowed at a public dinner.” After a last-minute price cut, however, the room was recorded by as being “crammed and suffocating” while Dickens read for almost three hours.

The screen remained in the Macready family until 2004 when it was donated to Sherborne by a direct descendant. It was in poor condition, but has now been comprehensively restored after a local appeal raised £22,000. Paper conservator Rebecca Donan has deliberately left some damage visible, including a candle burn from someone standing too close at night and scratch marks from a family pet.

The 18th-century mansion, whose future was in doubt after it closed as an arts centre and was sold by the local authority to a property developer, has now been fully restored by a trust. It re-launched this summer as The Sherborne and is open daily, with entrance free.