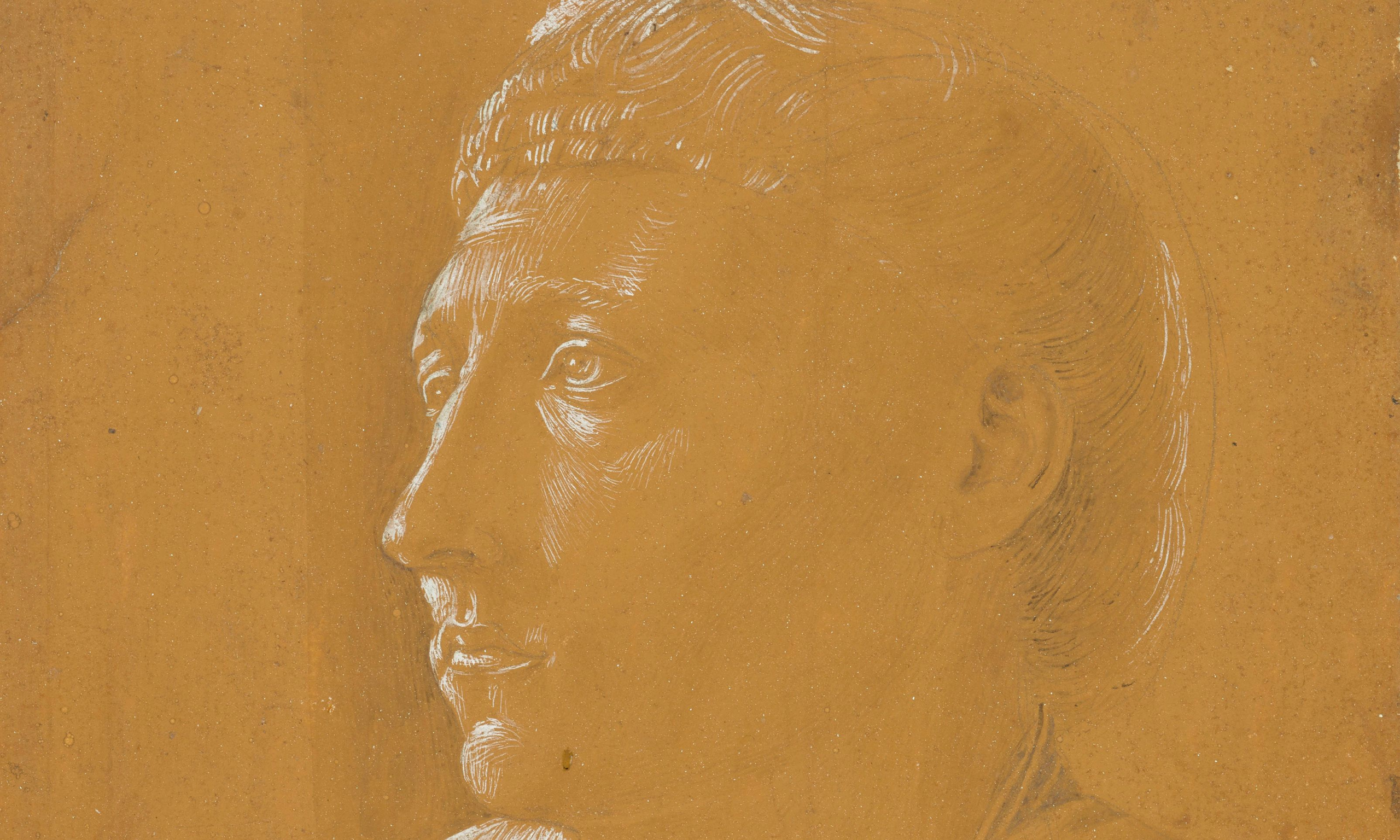

Fra Angelico, The bust of a cleric (around 1447–50) is included in the forthcoming exhibition Drawing the Italian Renaissance (1 November-9 March 2025)

A blockbuster exhibition of Italian Renaissance works on paper launching at the King’s Gallery in London later this year will include 12 works never seen in the UK including An ostrich, a chalk study dating from around 1550 attributed to Titian. Drawing the Italian Renaissance (1 November-9 March 2025) includes works by 81 artists spanning 1450 to 1600; more than 150 works will be on display from the Royal Collection, nine of which will be shown double-sided.

The Titian study was previously shown at the Istituto Olandese in Florence in 1976. “While the attribution to Titian has occasionally been questioned over the past 50 years, our curators at Royal Collection Trust are confident that the technique of black chalk on blue paper seen in this study is characteristic of the artist; although other Venetian artists such as Tintoretto used the same technique, the looseness of the outlines and especially the skewed up-close perspective is typical of Titian's mature works and no one else,” says a Royal Collection spokesperson.

An ostrich, a chalk study dating from around 1550, attributed to Titian

Other major works featured include Raphael’s The Three Graces in red chalk (around 1517–18)—a study of one model in three poses made for his fresco of the Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche in the Villa Farnesina—and A costume study for a masque by Leonardo da Vinci (around 1517–18), a sketch of a fantastical costume designed for the French king, Francis I. Thematic sections will examine topics such as artists’ understanding of the natural world along with the development of life drawing.

Martin Clayton, the head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, tells The Art Newspaper: “Rather than any major new research discoveries, a key focus of the exhibition has been on bringing to light and sharing with the public important and interesting drawings that have never been exhibited before, and in some cases, undertaking conservation on those works.”

He adds: “It is also the chance to reconsider artists of the period as draughtsmen in addition to painters or sculptors. For instance, we have a design for a lavish marble altar including sculptures of saints, the Virgin and Child, and a patron that is attributed to Andrea Sansovino [A design for a sculpted altar, around 1510], a major sculptor who is almost unknown as a draughtsman.”

Another significant piece on display for the first time is a larger pen and ink study of dogs by painter Parmigianino, Studies of dogs (around 1530), which shows “the dogs to have a sense of dignity”, Clayton says. The show also explores how artists used an increasing number of materials and techniques during this period, toning paper with a coloured wash for instance or adding highlights in liquid lead white. “The Italian Renaissance would have been impossible without drawing; it was central to every stage of the creative process,” Clayton adds.