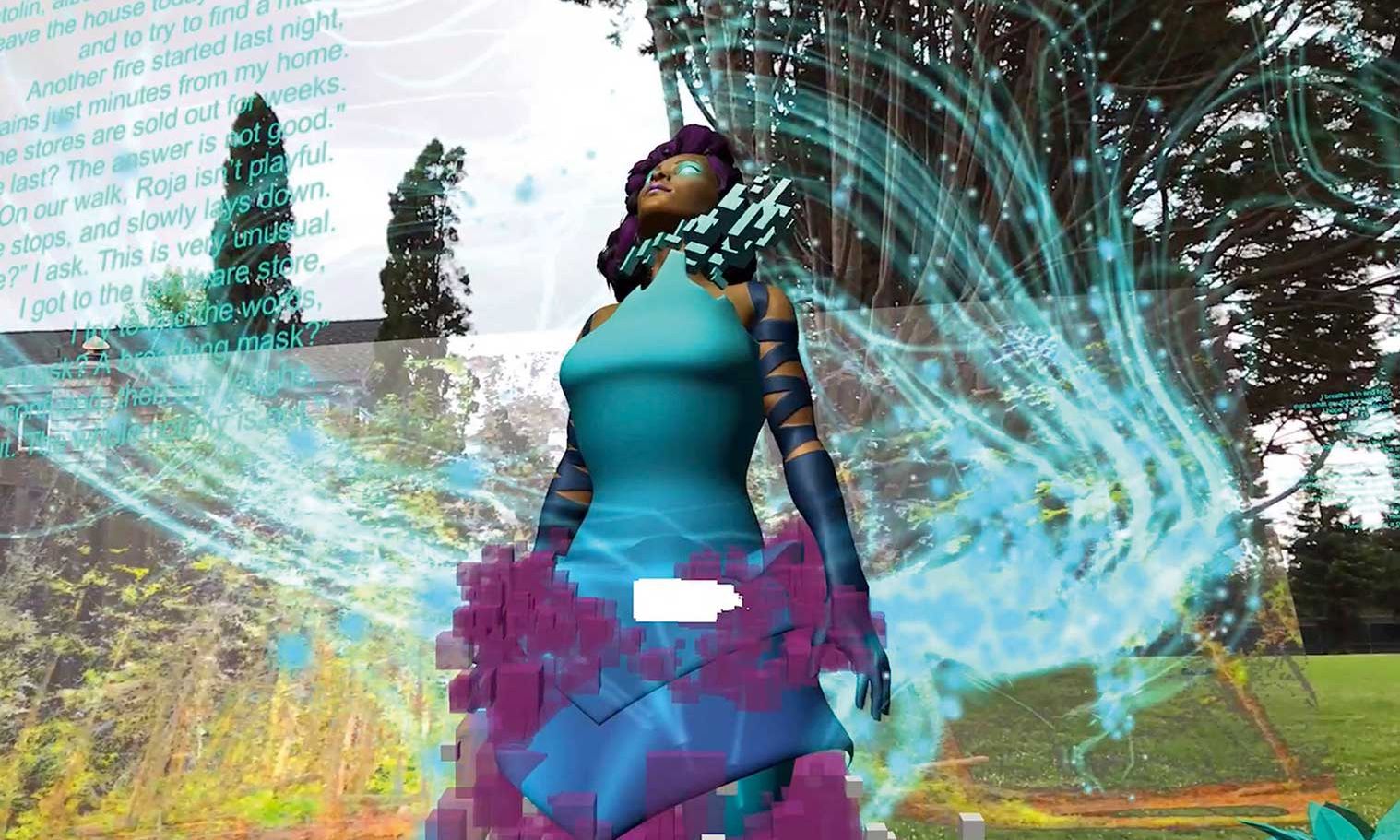

Digital Capture: Southern California and the Pixel-Based Image World, at the University of California, Riverside, explores digital imaging since 1962, including Sin Sol (2020), micha cárdenas’s augmented reality game © 2020 micha cárdenas

This autumn, when PST Art: Art & Science Collide opens at museums across Southern California, visitors will be able to see dozens of exhibitions exploring important environmental issues, from water ecology to Indigenous fire-management. What they will not see in nearly as much depth or breadth, unfortunately, are exhibitions on today’s most urgent technological issues.

Out of more than 60 shows, only a handful will focus on pressing digital-age issues like the impact of the internet or artificial intelligence (AI) on human creativity. And these tend to be at small university venues. One promising exhibition at the University of California, Irvine, features artists working with complex systems; another, at the University of California, Riverside, offers a deep dive into the history of digital-imaging technologies. (The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is taking on digital image manipulation.) Redcat, a gallery run by the California Institute of the Arts, has the only AI-themed show.

This near-vacuum is sadly in keeping with mainstream art museums’ treatment—or avoidance—of the most sweeping changes in 21st-century technology that impact the construction of individual identity, community and knowledge systems. Where are the big museum exhibitions focusing on the way that smartphones are rewiring our brains and algorithmic social media is undermining democracy? Where is the blockbuster on how generative AI is changing our culture, if not yet our consciousness?

Artists are not afraid of these issues. Refik Anadol, Nancy Baker Cahill, Ian Cheng, Carla Gannis, Holly Herndon, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Trevor Paglen and Alexander Reben, among others, have not only been working with AI—as well as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR)—but also, for the most part, working through their ambivalence about these technologies, recognising both the powers and dangers of the tech industry’s greatest “advances”. These artists are making ambitious work with and on Silicon Valley’s own tools, even when excluded from recent—and highly proprietary—developments in generative AI belonging to Google, Meta, Microsoft and OpenAI.

Yet most art museums, in their devotion to traditional objects and the realm of the real, are missing the digital boat—and might just end up shipwrecked on an island stockpiled with things. Several conditions conspire to create this blind spot, starting with curators who, typically trained as art historians, lack the knowledge or confidence to take on hardcore topics in science, engineering and maths. Yes, they are proud of “crossing over” to other disciplines, just as long as they fall in the humanities or social sciences. Claudia Schmuckli, who organised Beyond the Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI for San Francisco’s de Young Museum in 2020, says she was surprised by how many curators at the time told her they did not know how to even begin to think about the subject.

Then there is the fact that the vast majority of art museums are not physically equipped to show tech-based work. Most are still designed for displaying painting and sculpture, much as they did in the 19th century. Some do not even have reliable wifi, says Hershman Leeson, who began creating charming chatbots in 1997 with Agent Ruby and has since done important work on web-based surveillance and predictive policing, which involves racial profiling.

“Art institutions have always lagged behind artists—perhaps they don’t want to experiment by showing something that seems radical, because it appears to have no obvious history at the time it is made,” she tells The Art Newspaper. “But I find they are especially wary about investing in work that relies on technology, because the equipment changes and becomes obsolete so fast.”

Hershman Leeson explains that in her history of showing at museums, even those that supposedly specialise in new media, the expectation is that the artist delivers all the hardware and software, plus programmers to train staff in how to operate the work. This barrier of entry naturally keeps less accomplished or less persistent artists out of sight.

A question of funding

Lack of funding plays a role in another way, too. The mega-collectors and gallerists who so often help to underwrite big US museum exhibitions are more likely to be invested in paintings by blue-chip artists, whether Anselm Kiefer or Alex Katz, than in art made on gaming platforms like Unity. You can count major US collectors of new-media work on one hand.

That said, the situation is not hopeless. In New York, the curator Christiane Paul at the Whitney Museum of American Art has long advocated for digital art and recently organised an important show on Harold Cohen’s AARON, the earliest known AI programme for drawing. And gallerists like Steven Sacks of Bitforms in New York and, increasingly, Honor Fraser in Los Angeles have created prominent platforms for these kinds of artists. But these examples are outliers.

“Suffice it to say, there have not been a tonne of knockout museum shows examining AI,” says Jesse Damiani, who curated the group exhibition SMALL V01CE on questions of “machine intelligence” at Honor Fraser. “And when they do pop up, they more often feel like checked-box exercises than meaningful interrogations.”

Damiani, who is also a curator at Nxt Museum in Amsterdam, says another reason tech-fuelled work does not get enough play at museums is because its aesthetic lineage and the heuristics to assess its quality are still being established. “With a painting you find ugly, you would often give it the grace of thinking there is more under the hood. New-media art doesn’t get that,” he says. As for the scholarship that is taking place, he calls it an “uphill battle” that requires more than the usual commitment of curatorial time and resources.

All of this makes it particularly disappointing that so few museums in PST Art this year—which benefited from more than $20m in Getty funding and several years of development—are dealing with the AI elephant in the room or the mini-computers in our pockets. Even if AI was not such a hot topic when most of the shows originated five years ago, the outsize role of data mining and predictive algorithms in shaping voter and consumer behaviour was.

Redcat’s All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace will be the only AI-themed show in PST Art Photo: vog.photo; © Kite

For the 2017 edition of PST Art (then still called Pacific Standard Time), curators used some of their grant money to bring in experts from Latin America (that year’s theme) to co-curate shows such as Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 at the Hammer Museum. Why didn’t curators this time reach out to teams of computer scientists, VR developers and video-game designers? Instead, the new edition’s most notable collaboration, for an art installation at the Skirball Cultural Center celebrating trees, is between the filmmaker and writer Tiffany Shlain and the robotics professor Ken Goldberg—who happen to be married.

In this way, the PST Art subtitle, Art & Science Collide, proves a bit misleading. Expect shows that touch on science, mainly environmental, but the suggestion of such a dramatic encounter is off. The real collision will not occur until museums wake up to the techno-future that has already arrived.

• Jori Finkel is West Coast contributing editor for The Art Newspaper