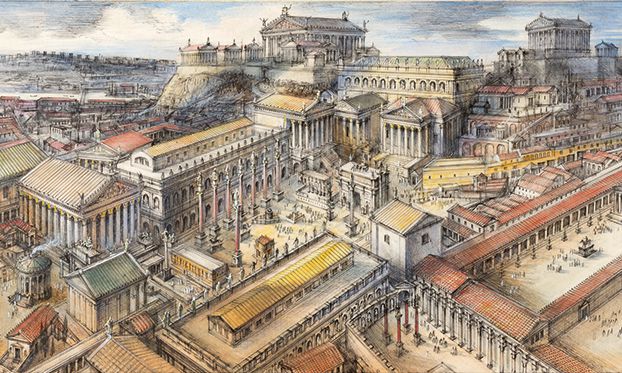

Alan Sorrell’s reconstruction of the Roman Forum in the fourth century, looking towards the Temple of Jupiter © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In this lavishly illustrated book, the drawing recreating the Roman mausoleum of Augustus makes it look like the grandest fairground carousel ever built. Augustus, the first Roman emperor, began work on it in 28BC, 42 years before his death, and it rose, drum-shaped—a radical new design for Rome, inspired by Etruscan and Greek examples—over a whole new district of the city created to memorialise his own divine glory. Originally it was studded with columns and sculptures, topped by a huge bronze statue of the emperor, set on a garden terrace and belted by a white travertine-clad wall 87 metres in diameter, the longest in the Roman Empire.

The mausoleum—the model for the Castel Sant’Angelo, Hadrian’s much better known mausoleum, later the palatial apartments of a pope—survives, battered but still truly monumental. The Ancient Roman historian Suetonius said Augustus boasted that he found Rome brick and left it marble, but the brick (and the Roman miracle material of concrete, which has kept the Pantheon and its gigantic dome intact for 2,000 years) proved more enduring. With many of Paul Roberts’s “Fifty Monuments”, his accounts of their long afterlives grip the imagination. The Augustan mausoleum, for example, lost its shining marble and elaborate decoration in the 1160s; by the 17th century it was used for bullfights and buffalo hunts; and in the 19th century became a theatre and concert hall. The block made to hold the urn of Agrippina, Augustus’s granddaughter and mother of the infamous Caligula, became a grain measure in the Middle Ages.

In the 20th century, Mussolini flattened all the surrounding buildings to increase the mausoleum’s domination of the setting, and apparently contemplated adding his own remains to its imperial history. Instead his body was buried in an unmarked grave in 1945, resurrected and stolen by supporters in 1946, recovered and hidden for 11 years, and moved in 1957 to his family’s vault in the small town of Predappio, where it has become a pilgrimage site for neo-fascists.

The watercolour reimagining the original splendour of Augustus’s mausoleum is by the French architect and archaeologist Jean-Claude Golvin, and is one of hundreds of illustrations in the book, ranging from Old Master paintings to engravings, including Piranesi prints, and photographs, including many by the author himself. One of the most beautiful illustrations is a golden recreation of a once gigantic lost temple of Jupiter. Given a two-page spread, it is the work of C.R. Cockerell, the 19th-century scholar and architect, whose designs include the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, where Roberts is Research Keeper of Antiquities. Many strikingly moody images are by the muralist Alan Sorrell (1904-74), whose archive is lodged at the Ashmolean. Sorrell’s career as an archaeological illustrator began when the great Kathleen Kenyon asked him in 1936 to recreate one of her sites for the Illustrated London News: the archaeologist Barry Cunliffe has described his work as equally inspirational as the star archaeologists Glyn Daniel and Mortimer Wheeler.

Officially the volume covers almost a millennium, from the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus that was begun in the late 600s BC, to the Column of Phocas, erected in 608AD in his brief reign before he was deposed, dragged through the streets and disembowelled. However, the title of Roberts’s book is actually a serious understatement: the man cannot resist an alluring side road, and takes in hundreds more sites than the advertised 50. You might wish that the former British Museum director Neil MacGregor had patented the idea when he published A History of the World in 100 Objects in 2010. But however hackneyed the title, Roberts’s romp through ancient and contemporary Rome is a cracker. Although it is a bit chunky as a pocketbook at 256 pages, with its maps and assurance that all 50 sites are visitable without applying to the Pope or an emperor for special access, the book is well worth employing to plot an epic city break.