Harrison Williams was born enslaved on a Southampton County, Virginia, plantation in 1847, but by December 1864, he was a free man and a soldier in the Union Army. Over the next four months, he participated in the capture of Richmond, Virginia, and saw the fall of the Confederacy.

Harrison was born to Solomon Sykes and Louise Williams in 1847. He, his parents, and his two siblings, Joseph and Henry, were owned by Jacob Williams. Parson worked on the Williams plantation early in his life, but by his teenage years, he was hired out to the Boykins Railroad Depot. This was a common practice during the Civil War when many southern railroads hired, rented, or owned enslaved people who replaced white laborers conscripted into Confederate military service. Through his job at the depot, Harrison kept up with major Civil War engagements and other crucial issues by examining discarded newspapers, brochures, and maps he found at the depot.

On December 2, 1864, seventeen-year-old Harrison and his brothers escaped and began their journey to freedom. That journey was interrupted when Harrison encountered a two-person slave catcher patrol, which apprehended him after earlier capturing and interrogating Joseph and Henry. Harrison offered his captors tobacco, and as they grabbed it, the three brothers attacked, overpowered, and killed one of the slave catchers and injured the other. They then raced through the forest towards the Blackwater River.

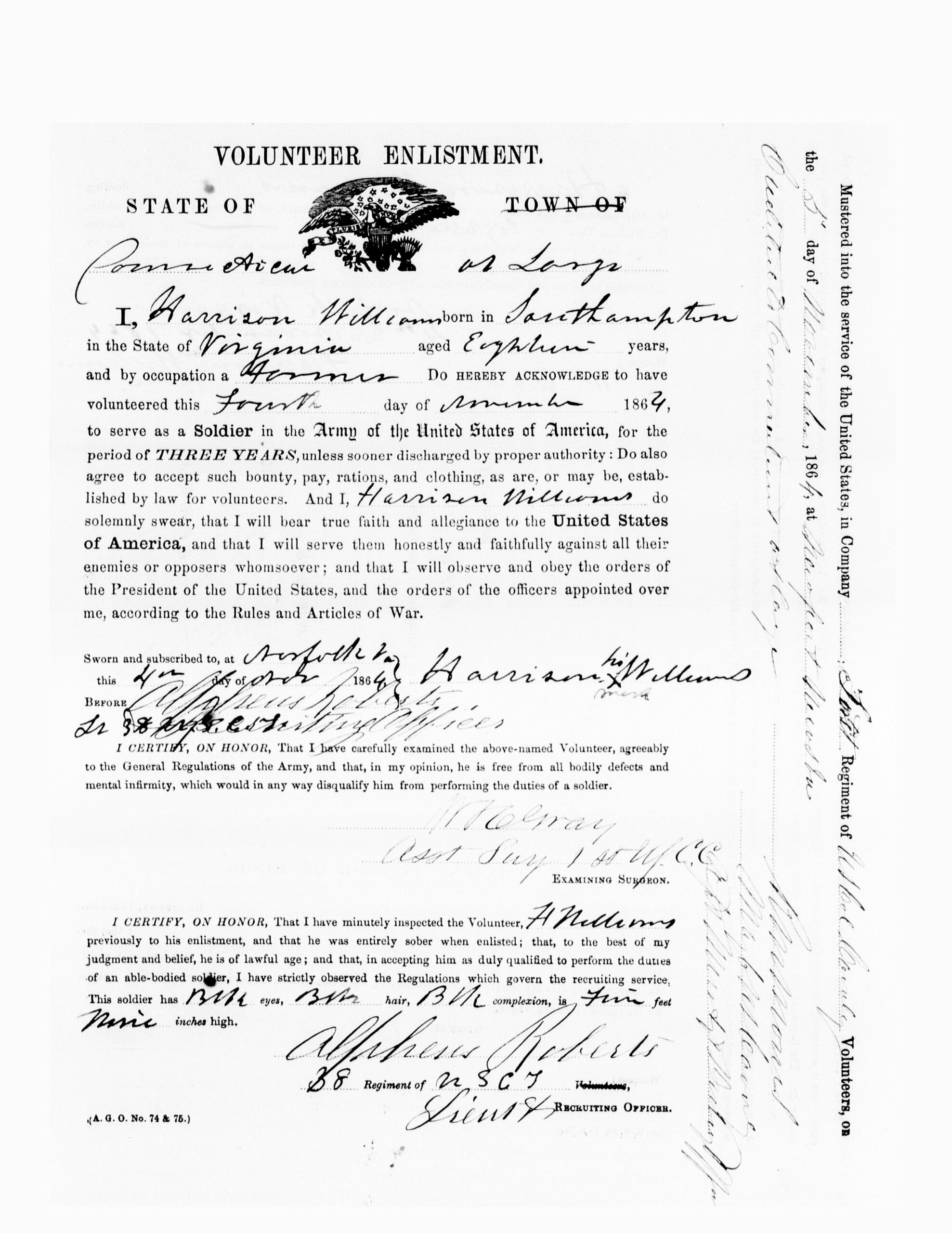

Two days later, on December 4, the brothers reached Norfolk County and encountered Union soldiers who occupied Camp Bowers Hill, Virginia. Because of their escape, Union Army soldiers were dispatched to find other Black men who fled Confederate-controlled areas into the Union-controlled towns and recruit them into the United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Harrison joined the Union Army and was assigned to Company I, 1st Regiment, USCT Cavalry.

As December 1864 ended, Harrison completed basic training at Fort Hamilton, sailed on a steamship up the James River, and joined the Army of the James near City Point, Virginia. There, he and other Union forces pursued what remained of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Harrison Williams was now a cavalryman with the XXV Corps, with nearly 14,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery soldiers, who comprised the largest Black unit in the United States Army.

On April 3, 1865, Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, commander of the XXV Corps, led Williams, who now called himself Parson Williams, and other members of the Corps who captured Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate Capital. After General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, Williams and the XXV Corps were assigned to the Rio Grande along the U.S.-Mexican border in May. They remained there until January 8, 1866. In 1866, the veteran returned to Southampton as Parson Williams and subsequently took his father’s last name, Sykes. Once there, he became a local hero for his self-liberation and his role in capturing Richmond.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Andre Fleche, “United States Colored Troops, The, Encyclopedia Virginia,” United States Colored Troops, The – Encyclopedia Virginia

Daniel Crofts, “Old Southampton: Politics and Society in a Virginia County, 1834-1869,” (University Press of Virginia, 1992)

David J. Mason, “The Self-Liberation of Parson Sykes, Enslavement in Southampton County,” (HMG ePublishing, 2022)

G. William Quatman, “A Young General and the Fall of Richmond, The Life and Career of Godfrey Weitzel,” (Ohio University Press, 2015)

Leslie Anderson, “Harrison Sykes alias Harrison Williams, Company I,” 1st U.S. Colored Cavalry, Harrison Sykes alias Harrison Williams, Company I | 1st U.S. Colored Cavalry (wordpress.com)

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.