We bring news that matters to your inbox, to help you stay informed and entertained.

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy Agreement

WELCOME TO THE FAMILY! Please check your email for confirmation from us.

Featured

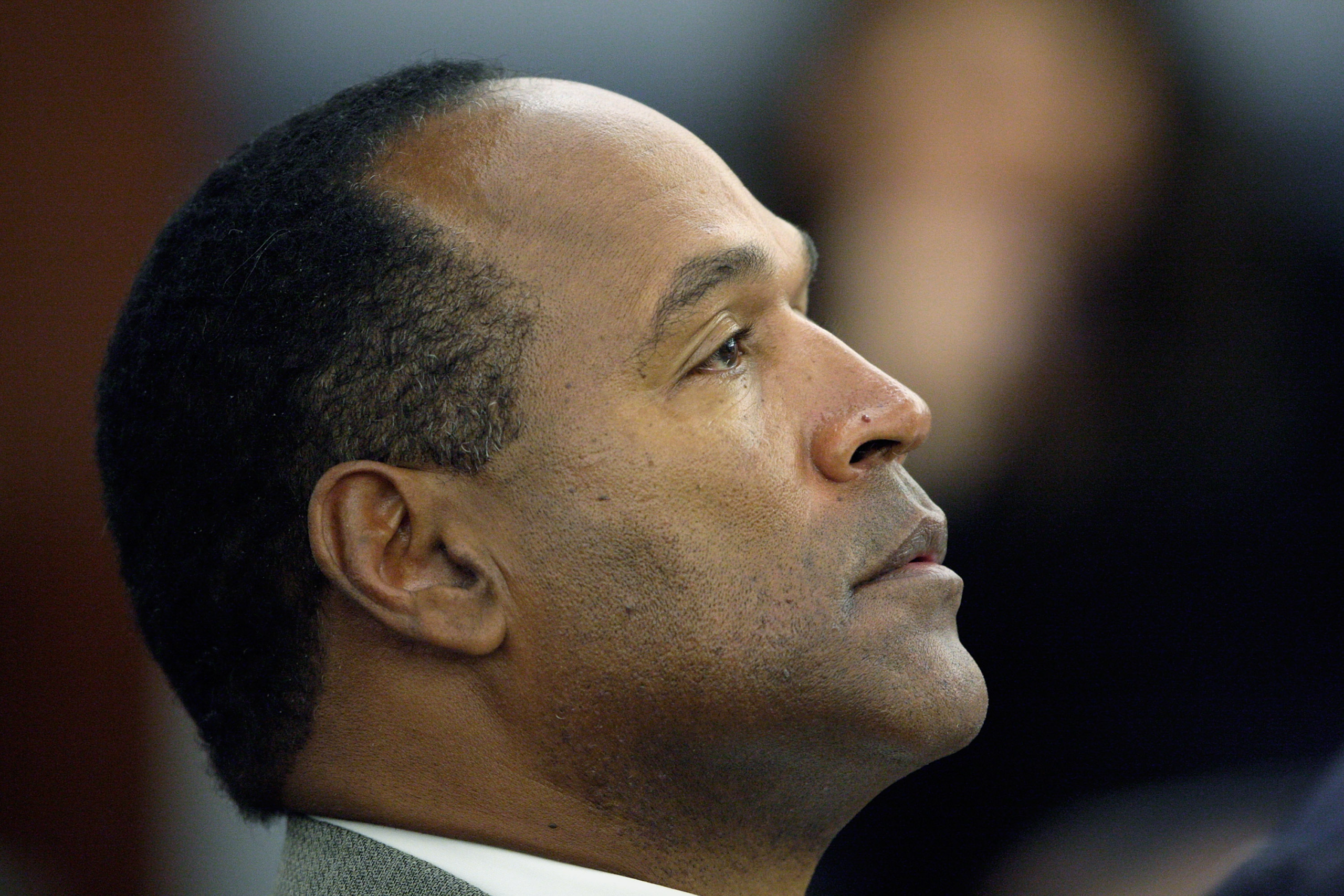

OPINION: Simpson, who died Wednesday at 76, was not a hero or a villain, but he was an all-American symbol.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Nearly 30 years later, I still remember exactly where I was when the infamous O.J. murder trial finally ended.

If I close my eyes, I can still see myself standing on the porch waiting anxiously for someone to open the door. I can almost smell the fall leaves that littered the front lawn of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity house in Auburn, Ala. Even though I was outside, I could still hear the news anchor on the living room television notifying the audience that a Los Angeles Superior Court jury had reached a verdict in The People of the State of California v. Orenthal James Simpson.

I banged on the screen door, but no one answered. I couldn’t hear any voices in the house, but I knew someone was inside, so I banged even harder. Still silence. “It’s Mike!” I yelled to no one in particular. “Open the door!” Still nothing. After a few minutes, someone came and opened the door.

“Not guilty,” my frat brother sighed with a combination of disbelief and relief. “Not guilty.” The words wafted past me, above the lawn, over the trees and into America.

As part of a small minority who did not actually see one of the most-watched television events in television history, I’ve held on to this memory for years. While an estimated 107.7 million viewers watched the conclusion of the O.J. trial, my story is not unique. Still, there is something that is even more fascinating about my flashback to this tentpole event in American culture.

It never happened.

I don’t actually remember the O.J. verdict. It wasn’t until I had to write about the 25th anniversary of the Los Angeles Riots that I realized that I’ve been conflating my personal recollection of the O.J. verdict with my actual memory of the Rodney King verdict and the uprising that followed. The O.J. trial began on Jan. 24, 1995 — just as I was entering the last semester of my senior year in college — and concluded on Oct. 3, 1995, during my first semester in grad school. So, at the time, I was kinda busy.

Now that Simpson is no longer alive, my memories are much clearer. Like many of the articles you will read over the next few days, I can now recall how Simpson’s acquittal enraged white America. I remember the collective sense of satisfaction and joy that Black people felt. Over the next few days, you will be inundated with reminders of this collective experience. You’ll be told how one man’s transgressions revealed the country’s racial divide and captured Black America’s overwhelming discontent with the two-tiered justice system.

Except, that never happened.

Deron Snyder

Associated Press

Associated Press

Michael Harriot

Deron Snyder

TheGrio Staff

Associated Press

Associated Press

One of the most fascinating things about history is our ability to construct an entirely new reality based on our individual need for a rational storyline. Scientists and psychologists understand that human memory is malleable and unreliable. But because the human species actually needs to make it make sense, we still convert these semi-fictional reflections to a crowdsourced, whitewashed narrative and enshrine it as “history.” This kinder, friendlier interpretation of our past is how a country where “all men are created equal” can reconcile the inhumanity of race-based human trafficking. It’s the only way a majority of Americans can believe that Black people are treated less fairly by police, financial institutions and employers yet still believe “America is not a racist country.”

Perhaps no single figure embodies America’s capacity for recreating its past more than the recently resurrected versions of Orenthal James Simpson.

Contrary to the current narrative, the Simpson trial is not what “held up a cracked mirror to Black and white America” and “exposed the deep divisions” between the two. The Simpson murder, LAPD investigation and the trial that followed took place in the still-smoldering ruins of the Los Angeles riots and the subsequent trial of the L.A. Four, 30 years after Martin Luther King Jr. warned the country that we would “never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.” President Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill was already exacerbating mass incarceration fueled by the Reagan-Bush war on drugs. African-Americans already had a deep mistrust of the police, especially the corrupt Los Angeles Police Department. We didn’t need O.J. to prove that America’s system of policing was corrupt and broken.

While Fox News described Simpson as an “accused killer” who embroiled the country in “racial animus,” most white people did not initially believe Simpson was guilty. Nearly a month after 95 million watched the coverage of the infamous Ford Bronco chase, only 37% of white Americans and 15% of Black Americans believed he was guilty of killing his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman, according to a July 1994 Wall Street Journal/NBC poll. By the end of the trial, 65% of whites thought Simpson was guilty while only 18% of Black Americans felt the same.

But “not guilty” and “innocent” are two different things. It is possible to believe the former Heisman winner killed Nicole and Goldman and that a racist criminal system and a corrupt police department tried to bolster the case with unethical tactics. Yet, when Black people cheered when O.J. beat his case, many white Americans wrongly believed him to be a hero in Black America. According to Maureen Dowd, one of the world’s most respected journalists, O.J. was this generation’s “Othello” — a “great American tragedy” that “drilled into the most sensitive parts of the national psyche, exposing conflicting views about race and policing and celebrity and legal equality.” I have no idea when that happened, either.

Like many white people, Dowd wrongly assumed that we were cheering for the man she once called a “gorgeous monster” when, in fact, the Black community loved O.J. as much as he loved the Black community — not much. Even when we erupted into cheers when he was acquitted, we were happy for Johnnie Cochran and the rare sight of a Black man defeating an anti-Black industrial criminal justice complex. We knew who Simpson was. His ability to run fast and smile big made him an icon to white America…until he was as disposable as the rest of the Black bodies that littered American history. Black culture didn’t embrace Simpson’s criminality any more than white America rejected his humanity. When the jury decided his fate, Black America wasn’t litigating his guilt or innocence. We weren’t even siding with him specifically; we were cheering against the system. We were rooting for everybody Black.

To be fair, it is not hard to understand why the entire country is still so captivated by this tale of race, murder and nonredemption. It is perhaps the purest example of America’s ability to Rumpelstiltskin a whole cloth of truth from a single thread of fiction.

Oct. 3, 1995, didn’t expose any rifts that didn’t exist before June 12, 1994, the date of the murders. The O.J. trial didn’t change Black people’s perception of America. But over time, it changed white people’s perception of one Black man. After Black people had protested peacefully, screamed loudly and exercised every possible measure of redress, the spectacle of a Black man killing a white woman exposed white people to Black people’s simmering discontent that they had conveniently ignored for generations. The verdict didn’t meaningfully impact Black people or white people. But, like the rise, downfall and the entire life of Orenthal James Simpson, it was truly all-American.

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His NY Times bestseller Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America is available in bookstores everywhere.

STREAM FREE

MOVIES, LIFESTYLE

AND NEWS CONTENT

ON OUR NEW APP