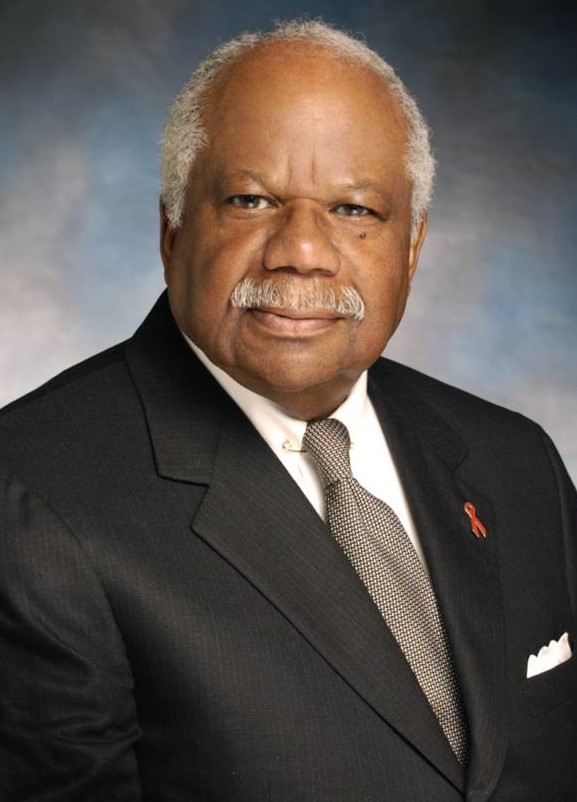

Beny Jene Primm, a pioneer in HIV/AIDS research and treatment and an anesthesiologist, was born on May 28, 1928, in Williamson, West Virginia, to a funeral director father, George Oliver Primm, and a mother, Willie Henrietta Martin Primm, who taught school. He had one brother, Gerome Primm, who became a funeral director.

In 1940 the family moved to The Bronx, New York, when Beny was 12. There, he graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in 1946 and then enrolled on a basketball scholarship at the all-male HBCU, Lincoln University (now coed) in Pennsylvania. In 1948, Primm transferred to West Virginia State College, where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in education in 1950, concentrating in premed, biological science, and German. While at West Virginia State he joined Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., played on the basketball team, and was a member of the campus Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

After graduating from West Virginia State, he entered the US Army as a Second Lieutenant, was assigned to its 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, and received training as a paratrooper. Primm was one of the first Black officers to command white troops after President Harry Truman integrated the U.S. military in 1948.

While in the service, Primm married Annie Delphine Evans in 1952, a music teacher with a degree from Fisk University, who worked as an educator until her death in 1975. They had three children, Annelle Beneé Primm, Martine Primm, and Jeanine Bari Primm Jones.

After fulfilling his military obligations, Primm was honorably discharged in 1953 and then traveled to Germany to attend Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg in Germany for one year. In 1959, Primm earned a Certificate de Fin d’ Etudes Medicaux with a specialty in pharmacology and Doctorat aux Medecin from the Université de Genève in Switzerland. He completed an externship in obstetrics and gynecology at Morrisania Hospital in the Bronx.

Starting in 1963, Primm worked as a weekend emergency room anesthesiologist at Harlem Hospital. In 1969, he founded the Addiction Research and Treatment Corporation (now called START Treatment & Recovery Centers) in Brooklyn. In 1981, Primm launched the Urban Resource Institute to protect spouses from domestic violence. Two years later, in 1983, through behavior observation and testing, he connected the relationship between IV substance abuse and AIDS and discovered that the disease among Black Americans far outnumbered the recorded cases in the LGBTQ community.

Primm was a medical consultant to three US Presidents, including serving on Ronald Reagan’s Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic in 1987. He was also one of the creators of the 1998 Congressional Minority AIDS Initiative, where millions of dollars were allocated to serve HIV and AIDS minority populations. He later became an advisor for the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

Primm wrote more than 30 peer-reviewed articles on addictions, and in 2014, he authored The Healer: A Doctor’s Crusade Against Addiction and AIDS with John S. Friedman.

Dr. Beny Jene Primm, the internationally recognized expert on HIV and AIDS, Chair Emeritus of the National Minority AIDS Council, and Vice Chair of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS, died on October 16, 2015, in New Rochelle, New York. He was 87.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

“Dr. Beny J. Primm Left a Long Legacy in Medicine, Public Health, and Social Justice,” https://vineyardgazette.com/obituaries/2015/10/29/dr-beny-j-primm-left-long-legacy-medicine-public-health-and-social-justice; “Dr. Beny Jene Primm, MD: May 21, 1928 – Oct 16, 2015,” https://www.jfosterphillips.com/obituary/3354481; Otis D. Alexander, (2019) Dynasty: Blacks in White Coats, (New York: Beyond the Bookcase), pp. 110, 111, 166, and 167.

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.