Margaret Vernell James Strickland was a leading scientist on termite diversity and a Civil Rights activist. She was the first professionally trained Black woman entomologist and the third Black female zoologist in the United States. She was born Margaret Vernell James on September 4, 1922, in Institute, West Virginia, to Rollins Walter James, who had worked with scientist George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, and Willie Luella Bolling James.

Margaret, the fourth of five children, spent much of her time in the library on the campus of West Virginia State College (WVSC) collecting insects she had gathered from nearby forests. In 1936, after graduating from the WVSC Laboratory High School, Collins, then 14, was awarded an academic scholarship to study biology, physics, and German at WVSC.

In 1943 Collins received a Bachelor of Science degree followed by a 1949 Ph.D. in entomology from the University of Chicago. Her dissertation was Difference in Toleration of Drying among Species of Termites (Reticulitermes), in which she investigated three species of termites confined to dunes. Her work was published in the peer-reviewed journal Ecology in 1950.

In 1951, Collins was named Dean of the zoology department at Florida A&M University (FAMU) in Tallahassee. While there, she became a participant in the civil rights movement when she voluntarily transported the Student Council as it led a bus boycott in Tallahassee and used her automobile to transport Black men and women to their jobs during the boycott.

In 1961, Collins received a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to conduct research at the Minnesota Agricultural Experimental Station in St. Paul. She briefly returned to FAMU in 1962, and then moved to Washington, DC, the following year when she was named a professor at Howard University. While at Howard, Collins led an expedition to Mexico. In 1969 Collins became a faculty member in the biology department at Federal City College (now the University of the District of Columbia), working there until 1976. While there she organized a symposium for the American Association for the Advancement of Science on the topic, “Science and the Question of Human Equality,” during her tenure.

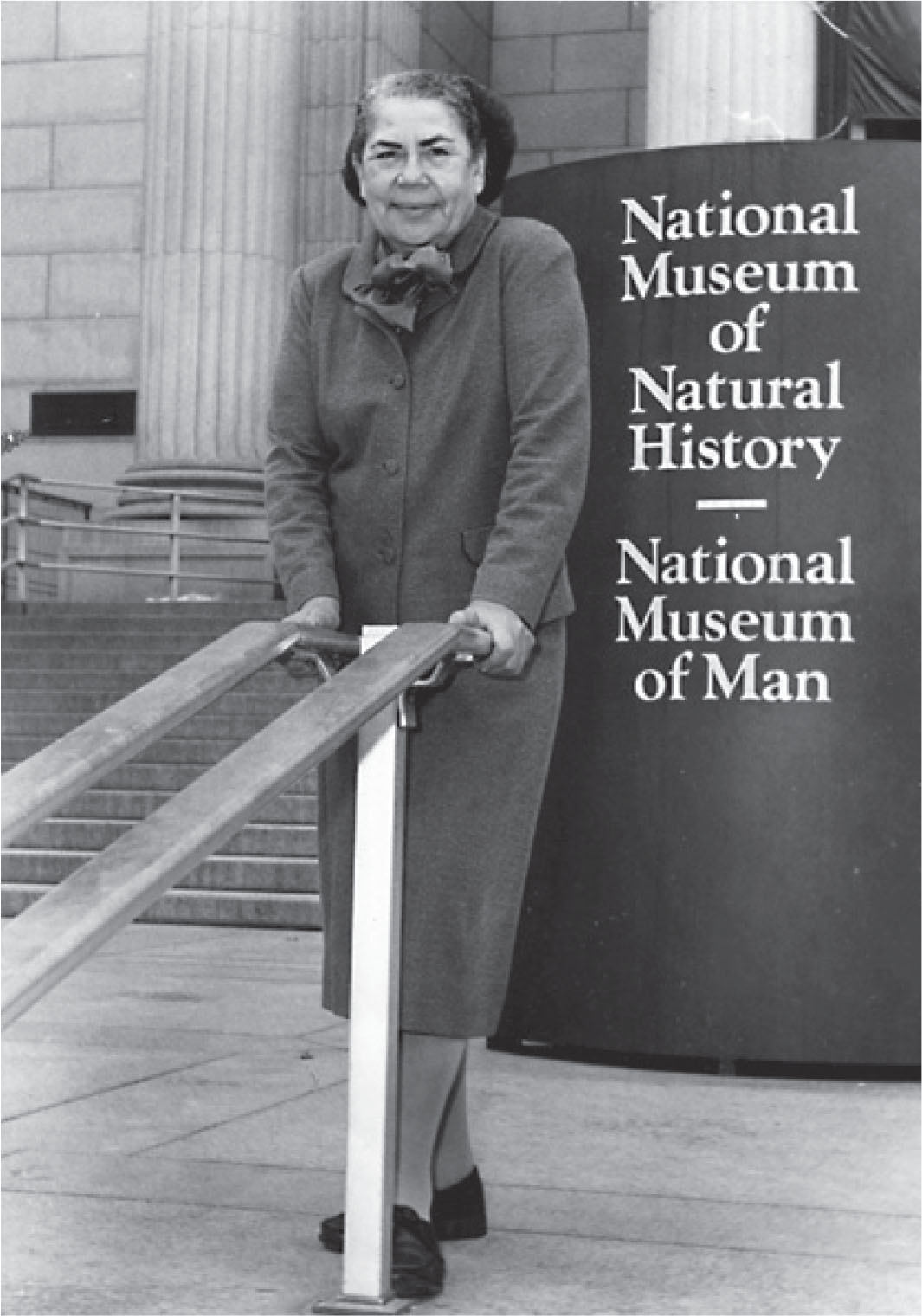

Collins returned to Howard University in 1977 and retired in 1983 at the age of 61. Afterward, she served as a senior researcher in the Department of Entomology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in DC. Six years later, in 1989, she discovered a species of Neotermes lucky Termites in Florida during an expedition. In 1993, she was part of an insect-collecting expedition in the tropical forest of Guana Island, British Virgin Islands.

Collins, who published and co-authored more than 40 research papers, was married twice: first to Bernard Eustace Strickland, a medical doctor who served in the 761st Tank Battalion, the US Army’s first all-Black battalion during World War II, and then to Herbert Louis Collins, who also served in the US Army during World War II and the father of their sons, Herbert Louis Collins Jr. and James Collins.

Dr. Margaret Verdell James Strickland Collins died of congestive heart failure on April 27, 1996, in the Cayman Islands. She was 73.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Lisa Temaki’s, “Margaret Collins: Scholar, Civil Rights Activist, and Mentor,” Margaret Collins: Scholar, Civil Rights Activist, and Mentor | Smithsonian Institution Archives; M. Strickland, “Differences in Toleration of Drying between Species of Termites (Reticulitermes),” https://www.semanticscholar.org/author/M.-Strickland/48900405; Olivia Foster Rhoades, “Margaret Strickland Collins: Civil rights activist and “termite lady,” Margaret Strickland Collins: Civil rights activist and “termite lady” – Science in the News.

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.