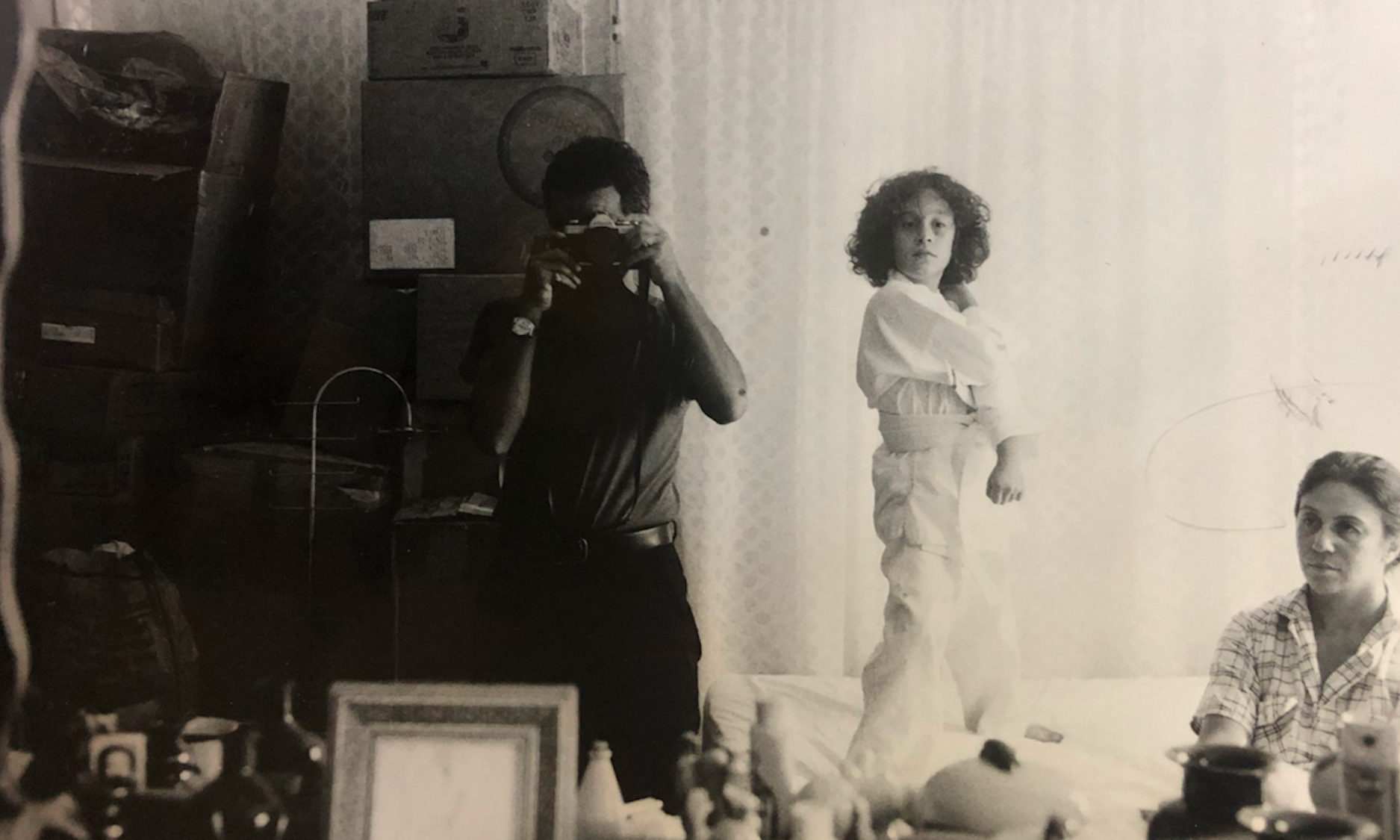

Still from A Revolution on Canvas with, from left to right, Nickzad Nodjoumi, Sara Nodjoumi, and Nahid Hagigat Photo: Courtesy HBO

When the artist Nickzad Nodjoumi decided to flee Iran in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution, he had to move fast. An image of one of the paintings featured in his 1980 solo exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art had appeared in a newspaper, accompanied by an article describing his work as “treasonous”. A friend advised him to leave immediately. “I was out of the airport at nine o’clock,” Nickzad says in the new HBO documentary A Revolution on Canvas. “At 12 o’clock, Saddam Hussein attacked the same airport.” This was the beginning of the Iran-Iraq War, which would last eight years and kill around 1 million people. As Nickzad boarded a plane bound for the US, he left more than 100 of his works behind at the museum at the mercy of a group called Hezbollah, which helped the Ayatollah consolidate his power. Decades later, Nickzad and his filmmaker daughter, Sara Nodjoumi, set out to find out what happened to the paintings—and get them back.

HBO describes A Revolution on Canvas as a “political thriller and verité portrait documentary”, and as much as the search for the missing paintings provides structure to the film, at its heart it is the story of a flawed man who continually puts his own idealism before all else. Directed by Nickzad’s daughter and her husband, Till Schauder (When God Sleeps, The Iran Job), the documentary draws largely on interviews with curators, archival video, photos of the revolution and, most importantly, footage of Nickzad’s extended family to paint a portrait of the dissident painter as seen by those who were supposed to be closest to him but who always lost out to the cause.

Nickzad is nothing if not a serious revolutionary. Involved in the many leftist protests of the 1960s and 70s as a young man, instead of a reception after his wedding, he and his new wife, the artist Nahid Hagigat, went to a protest—a party would have been a “bourgeois thing you’re not supposed to do”, he tells his daughter in the film. At the time, Nickzad had a particular fervour for the pro-democracy movement that sought to depose the Shah of Iran, going so far as to leave his family behind in New York while he travelled to Tehran to join the street protests in the late 1970s, calling his wife and four-year-old daughter “every couple of months”. (“Did you miss me?” Sara asks during a sit-down with her father years later. “No,” he answers.) In a memorable scene towards the end of the documentary, Nickzad grins proudly as his grandkids sing a song they wrote in support of the 2022-23 Mahsa Amini protests. The moment is notable as perhaps the only time he smiles in the whole film.

Nickzad was born in western Iran in 1942, and he met Nahid in art school. She moved to New York in 1968; he followed a year later. There, Nickzad became involved in seemingly every leftist protest movement—anti-war, Civil Rights, the Black Panthers—and particularly the Iranian Students Association in the United States. In 1974, Nickzad returned to Iran for an exhibition of his work, bringing about a dozen of his wife’s etchings with him; the two artists sold all their work. The same thing happened the following year. Both Nickzad and Nahid were well on their way to success. But while in Iran, Nickzad was arrested by the secret police and interrogated about his political activism in the US; the chairs used in these lengthy and arduous interrogations often appear in his work. When he returned to New York, he and Nahid were married—despite protests from her parents that their Jewish daughter get involved with a Muslim man.

When Nickzad flew out to join leftist protesters in Tehran, Nahid moved with their daughter to Florida. He called it “the end of our marriage”. “I was at every protest,” Nickzad tells his daughter. “I was everywhere.” Meanwhile, Nahid tells him: “I looked for you in the news.” When the Shah left Iran and Ruhollah Khomeini arrived from exile in Paris, the postrevolutionary purge began—thousands of non-Islamic protesters and revolutionaries were arrested, and hundreds were killed. Nickzad was among the detained and lucky to get out alive. (“After that, did you join more protests?” Sara asks him. “Of course!” he answers.)

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, which Hezbollah saw as a symbol of the Shah’s decadence (filled largely with works by Western artists), was one of the first places taken over after his ouster. Nickzad’s exhibition, A Report on the Revolution, with its wry political commentary on power in general and the hypocrisy of the newly formed Islamic Republic specifically, was indicative of the kind of anti-Islamist opinions Khomeini sought to quash. “All of his work was anti-Revolution,” Nahid says of her husband. In Nickzad’s own estimation: “Khomeini was portrayed as an angry man, and everything else was blood and fury.”

The paintings were taken down and rumoured to have been either destroyed or stored in the basement. Years later, Sara became determined to find out if they are still around—and if she could return them to her father. She seeks help from an anonymous Iranian filmmaker (“It’s just a film. You don’t want to risk your life,” the filmmaker warns), the museum’s former director and several other people on the ground, trying to get access to the mysterious museum basement.

Sara was likely hoping that the search for her father’s paintings would bring them closer together. However, like the most recent Iranian protests, the situation is left unresolved. Whether or not they find the paintings and can bring them back, as much as this means to Nickzad and Sara, slinks into the background as a secondary plot line—to the point that, by the end of the film, the viewer is left with a feeling of indifference to this outcome.

“We could have been a very happy family, but Nickzad was always a revolutionary inside, and nothing in this world could have made him calm,” Nahid says, adding that her own artistic career suffered greatly as a result. “Women create, usually men destroy.”

“If it wasn’t for me, she probably would have had a better life,” Nickzad says of Nahid. When Sara asks her father if he has any advice for the young Nahid, he answers: “Don’t get married.” He does not appear to notice how much these words hurt his only child.

As Mao Zedong (a great influence on Nickzad) once said: “Women hold up half the sky.” But the Chinese leader’s collectivisation efforts greatly reduced women’s roles as individuals and instead gave them the task of serving as community caretakers. It seems Nickzad did the same in his own family—touting the accomplishments of women at large, while at the same time letting his needs trump those of his wife and daughter. The hypocrisy of revolutionaries goes both ways.