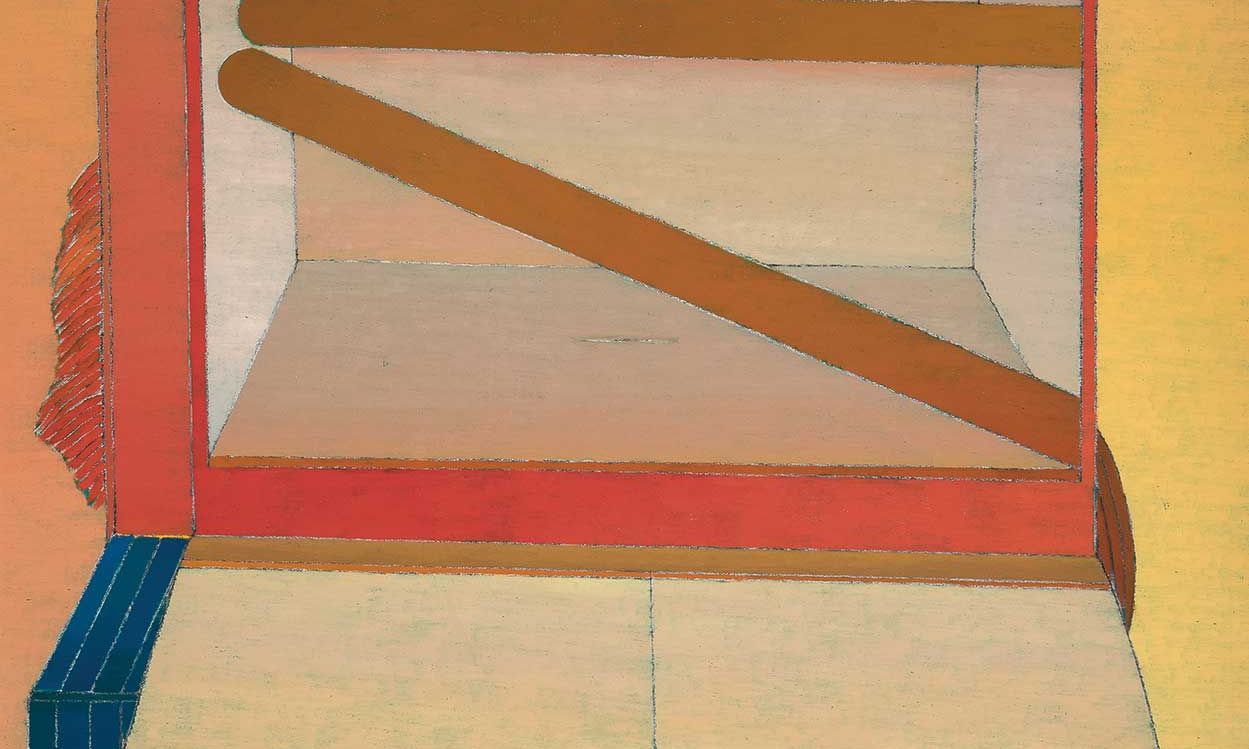

Strange allure of the figuratively abstract: in Miyoko Ito’s Interior Presence (1971), the furniture-like elements also suggest a compartmentalisation of the mind

Photo: James Prinz

The life and work of Miyoko Ito (1918-83) remains relatively unknown. If the

Japanese-American painter and printmaker is known at all beyond her adopted hometown of Chicago and the American Midwest, it is as a regional artist, a reductive label for someone well regarded by her peers and driven in her practice. This new book positions her within the broader fields and currents of art histories, allowing readers to understand the artist and her works in a more meaningful context.

At 460 pages long, Miyoko Ito: Heart of Hearts is a mammoth publication. Its author, the writer and curator Jordan Stein, first encountered Ito’s work in 2015. His tale of the “slow-burning treasure hunt” of tracking down the artist’s work over several years during the course of researching the publication is compelling in itself.

The greater part of the content is given over to full-page, beautifully produced, images of works of art. The book also shares facsimiles of archival letters, exhibition ephemera, photographs and reviews, all of which give a deeper sense of Ito’s practice, motivation and reception. There is a section with installation shots from two exhibitions of Ito’s work that were held in 1971 and 1980. Around half a dozen pages of thumbnail images, rescued from photographic slides, are presented as reference documentation for future researchers. Accompanying this primarily visual feast is a transcription of an interview with the artist from 1978 along with Stein’s new essay on Ito’s life and work.

Born to Japanese parents in Berkeley, California, Ito and her family moved to Japan in 1923, arriving in the wake of the Great Kanto earthquake. It was a place Ito described as both “very wonderful” and “very traumatic”. The family returned to Berkeley in 1928, and ten years later Ito enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, to study art practice. After Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan in December 1941, Ito was forced to leave her studies and sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center, an internment camp south of San Francisco, from April to October 1942, along with other

American-born citizens of Japanese ancestry. Upon her release from internment, Ito undertook further studies, first at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, then at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Early landscapes and interiors in watercolour and pastel soon gave way, in the mid-1950s, to arrangements of interlinking shapes rendered in hazy tones of blue, green, yellow and orange. At this time, she also developed a new underpainting technique, basing paintings on improvised drawings. By the end of the decade her hard-edged forms yielded to something softer and more bodily in nature, such as the richly coloured Kalamazoo (1959), itself emblematic of her experiments in oil.

In the late 1960s, Ito developed a unique approach that would sustain her until the end of life. In works such as Layered Presence (1968) and Interior Presence (1971) she began to explore the interface of portrait and landscape. To be more precise, it was the interface of self-portraiture and place and, therefore, an artist grappling with the relationship between inner and outer worlds.

While the Chicago art scene was divided between figurative Imagism and abstraction, Ito occupied a point between the two. The Imagists had begun in 1966 when a group of six recent graduates from the Art Institute of Chicago, including Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt, exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Centre in Chicago’s South Side, later the venue for Ito’s solo show in 1971.

Support from Phyllis Kind, the Chicago art dealer, and a two-year grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1973 furnished Ito with the means and the time to concentrate completely on her work. Ito’s metaphysical concerns separated her from her Imagist contemporaries and aligned her more closely to an older generation of artists including Helen Frankenthaler and Arthur Dove. Those concerns are evident in Ito’s Heart of Hearts, Basking (1973), a painting that seems to elide the body, interior space and exterior landscape in an intriguing fashion.

The influence of Japan and Japanese traditions on Ito’s work is considered briefly in Stein’s essay too. He points out that Ito herself seemed to recognise this influence only after others pointed it out, as was the case with comparisons made between her work and the geometry and architecture of the Japanese Heian period (794-1185). Other resonances are noted between the titles of works and Japanese translations, placenames and even possible thread-like visual signatures and connections to wabi-sabi (a Japanese aesthetic that recognises the beauty in simplicity, authenticity and imperfection). Mention is also made of Ito’s use of drawing pins around the edges of her paintings in relation to her incarceration at Tanforan.

Despite its enormous visual extent, this publication is only a beginning, an essential introduction to Ito’s life and work. Given her relative obscurity, Stein’s introductory approach in this book is understandable. However, the range of questions it raises, as well as the extensive visual component, position it as a new beginning for much needed research on the artist.

• Jordan Stein, Miyoko Ito: Heart of Hearts, Pre-Echo, 460pp, 160 colour illustrations, £70 (pb), published 31 January 2023

• Beth Williamson is an independent writer, critic and art historian