[ad_1]

The Shed under construction, February 2018.

ED LEDERMAN

In the makeshift office currently occupied by Alex Poots, the director of the future New York performance venue to be known as the Shed, is a curio with great significance for those of a certain cast: a music box gifted by the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. Known for his pioneering use of avant-garde sounds and expansive multi-day works that aimed to engage no less than the whole of the cosmos, Stockhausen was not the kind of composer whose métier would seem suited for a music box. But there it was, in the homey—even hokey—form of a wooden contraption filled with metal gears to summon soundings from Tierkreis (1974–75), a series of works devoted to the Zodiac.

“I got this call asking, ‘What’s your star sign?’ ” said Poots, who had worked with Stockhausen on programs of his music in the past. After that came a gift, signed by the artist and custom-generated for a Gemini.

Shed director Alex Poots.

COURTESY THE SHED

Fitting strange creations into unlikely boxes has been something of a specialty for Poots, who prior to assuming the top job at the Shed worked as the director of the Manchester International Festival in England and the Park Avenue Armory in New York. Neither was a small affair, but nor did they function at quite the same scale as an ambitious and closely watched new venue being built from the ground up with some $500 million from a start-up capital campaign seeded by heavy hitters including former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg (who gave $75 million) and the real-estate developer and businessman Frank H. McCourt (whose recent $45 million donation garnered naming rights for the Shed’s main performance space).

Asked about a possible lineage for the kind of institutional positioning he imagines for the Shed once it is fully operational and commissioning work in different disciplines, Poots thought back to the Ballets Russes in Paris, the Public Theater in New York, the Young Vic in London, and the Paris Opera. “There are pockets of deep expertise in all of those places that allow the Shed to emerge from something that came before,” he said. “We’re bringing bits of that, bits from the visual art world, and then the more experimental or more adventurous end of pop—we take strands from all three and wire them into the Shed.”

Some future programming was made public with the recent announcement of 2019 events to include a history of African-American music as staged by the filmmaker Steve McQueen and record producer Quincy Jones; a collaboration matching the painter Gerhard Richter with the musicians Steve Reich and Arvo Pärt; a performance featuring the poet Anne Carson; and an exhibition for the artist Agnes Denes. But first comes a sort of prologue, starting May 1 and running through May 13, in an empty lot across the street from the institution’s future home on Manhattan’s far west side.

Bundled under the title “A Prelude to the Shed,” the mix of performances and presentations will transpire in a pop-up structure conceived by Kunlé Adeyemi of NLÉ Works and the artist Tino Sehgal, who designed what a series description calls “a temporary space in which dancers move and reconfigure the structure in a fluid integration of architecture and choreography.” The daily and nightly lineup includes music (by Abra, Arca, Azealia Banks, Total Freedom), dance battles (organized by Reggie “Regg Roc” Gray), and Schema for a School, an “experimental course” to devise new modes of learning as imagined by Asad Rasa, Jeff Dolven, and D. Graham Burnett (of Cabinet magazine).

Abra, performing at “A Prelude to the Shed.”

COURTESY THE SHED

Asked how the Shed, as an institutional arts center, will differ from the festival model he has worked with before, Poots cited the Prelude program for the manner in which it “shows one way of how time and space can exist within an arts center framework. The Prelude tries to imagine an answer to that question but in a contained, controlled way”—with a capacity of 500 per day, as opposed to upwards of 3,000 that could (depending on the building’s malleable configurations) fit into the Shed’s permanent home. “The board is interested in experimentation: how do you not just create an arts center that is like all the other arts centers,” Poots continued. “So we have taken some of the format of the festival, some of an arts center, some of a museum, and some of a pop venue, and created a space that can accommodate a lot.”

Beyond the Prelude, Poots said that the Shed, which is scheduled to open in spring 2019, will differ from his previous home in the Park Avenue Armory—but in a variety of ways and on a case-by-case basis. “The Armory has a very clear history and DNA and purpose. It’s a singular space,” he said. “The Drill Hall kind of tells you what to do—if you work with the Drill Hall, there’s a synthesis between the work and the building and the room. It demands respect and accommodation in a way.

“To me that is almost the opposite of the Shed, which is like a tool box that can adapt to a new idea that an artist is developing. An artist can start off in a gallery direction and end up thinking, ‘Well, actually, it’s also theater’—so we just move it upstairs. We control the calendar, we control all the commissioning. We can adapt. We’re a place where artists can experiment with an idea and bring it to life, and then it can go into the world after it’s been presented here.”

The site for “A Prelude to the Shed.”

TIMOTHY SCHENCK

How much can he even conceive of what “here” will mean, exactly, in a Hudson Yards area that has been developing at a delirious pace, with office towers rising amid gleaming upscale residences and retail spaces the likes of which have not been seen in Manhattan since the minting of Midtown?

“We’re on city land and we’re a not-for-profit—I wouldn’t have taken the job if that wasn’t the case,” Poots said. “The Shed has a civic responsibility to the city and the Chelsea area, which has a lot more diversity than people maybe imagine, and the Shed should be for all of them. We’re trying to make it relevant to the five boroughs.”

By way of example he cited FlexNYC, a free three-year dance-oriented residency program affiliated with the Shed for young people across the city to engage social issues through movement, and DIS OBEY, a similar project geared toward poetry and the written word. The same week that the latter program was announced, Poots said, some participants asked for help in organizing a gun-control march. “So we were already useful. It makes a real connection. When we open, we’re hopefully more relevant to the city than we were three years before.”

How might relevancy and audience engagement work in the midst of what some have maligned as developers’ follies—such as Thomas Heatherwick’s Vessel, a polarizing 150-foot-, 2,500-step-tall sculptural incursion that will lure High Line–trotting tourists right outside the Shed’s future home? “I think it’s great it’s free,” Poots said. “It could be like the Eiffel Tower, which you have to pay for, and I think it will attract certain kinds of people who would not normally go there. I’m seeing it as a magnet. I’m sure people will go to that not knowing about the Shed—and then we can invite them over.”

Sentiment of the sort jibed with what Poots described as a vested interest in democratization of the different kinds of art the Shed will engage. “I deeply believe in the fact that your ability to be a great artist is not predicated on the type of art form you choose to practice. I grew up in a world that didn’t bat an eyelid at or relegate great artists as ‘low art’ in a disparaging fashion or elevate other artists, because they happen to be of the European fine art tradition, as ‘high art.’ That always made me deeply uncomfortable. None of it made any sense to me. From my perspective, a Joni Mitchell or James Brown or Leonard Cohen song is every bit as good as a George Benjamin aria.

“We’ve spent the last 100 years trying to undo all of that, and if I’m going to be given a new building and a chance to build from scratch, it’s not about being eclectic—it’s about being fair and democratic. With the array of stuff we’ve got—and we’ve only amassed nearly half of it—even that is a much wider purview of artists and audiences than any other arts organization I’ve ever been involved with.”

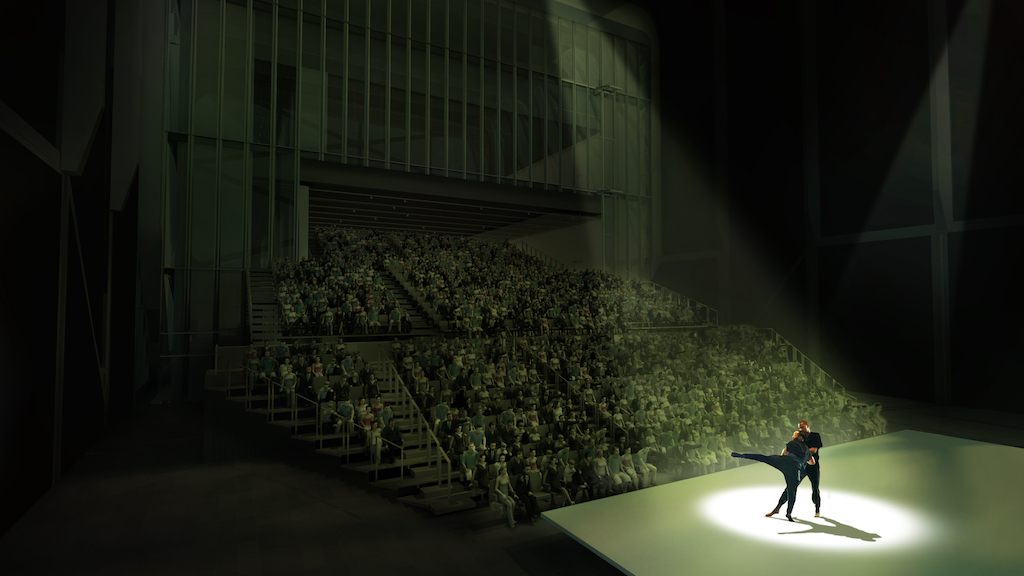

Rendering of the McCourt, the Shed’s main performance space.

COURTESY DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO/THE ROCKWELL GROUP

How will pricing work for shows of different kinds courting different kinds of audiences?

“I think free is great and I think really high prices are great. I think people who can afford it should pay, and I think we should be very accessible. If you go to the Barclays Center to see Jay-Z, there are tickets at $800 if you want to have dinner—and people are paying for them. And people who pay $120, a lot of them are not that well-off either. Are we going to be like that? No, because we’re not-for-profit. But why would people who are well-off and are paying $300 on Broadway get free tickets when there are people who deserve them much more? Why are we giving tax cuts to the rich? I think there’s a civic responsibility, and New York does that really well, to be fair to New York.”

Aspirations for the Shed and its commissioned projects will not necessarily end in New York, Poots said of an institutional desire to turn new works into touring productions and tap organizations in other locales as co-commissioners. “Even though it’s the Shed and there are enough resources to do it well, we will fail if our shows only come out once in New York and then don’t go anywhere. I’m just figuring out how we will do it because right now other things are more essential. I’m up for that—that’s excitement. Things don’t land perfectly formed always, or finished. Artists might make changes over time—even doing a run for a six- or 12-week period, looking at the same thing over and over again, it’s like a rabbit in headlamps. Sometimes you need to go away for three months, come back to it at the next presentation, and go, ‘Oh, I know how to fix that!’ “

In any case, the boundaries around and within particular Shed presentations will likely shift as formats change, each in their own way, Poots said. The collaboration between Gerhard Richter, Steve Reich, and Arvo Pärt, for example—“that’s running for every hour, on the hour, eight hours a day, six days a week, for eleven weeks, with a 14-piece ensemble. That is a very different gallery experience than anything I’ve run into. The format is a dance. The rules of engagement change.”

[ad_2]

Source link