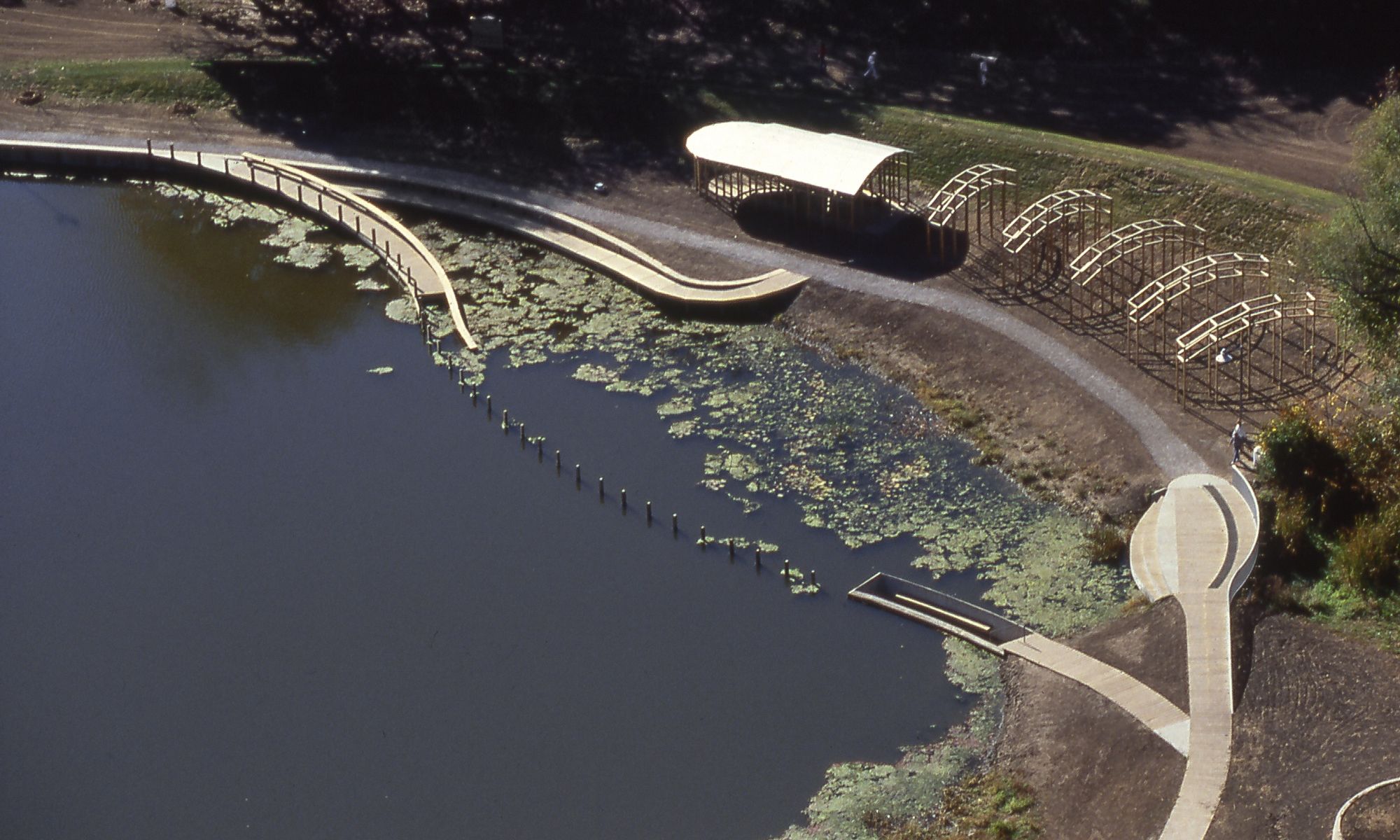

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond-Double Site, Des Moines, Iowa, 1996. Photo © Mary Miss, courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation

For close to 30 years, visitors to Greenwood Park in Des Moines, Iowa, have been able to explore the quiet setting of a lagoon, accessible through a series of structures by the pioneering environmental artist Mary Miss. The harmonious environment, a site-specific work titled Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1989-96), was commissioned by the Des Moines Art Center (DMAC) for its permanent collection and is thought to be the first urban wetland project in the United States. Now the DMAC plans to demolish it, in a move that goes against the artist’s wishes and is raising concerns about the institution’s stewardship responsibilities.

“This outdoor environment has deteriorated to the point where multiple elements are unsafe to remain open to the public and are no longer salvageable,” the DMAC’s board said in a statement last week, citing exposure to water and harsh weather. The board also sent a letter to Miss that noted that despite “regular maintenance and a partial repair project in 2015, today, nine years later, Iowa’s environment has prevailed… the reasonable maintenance the Art Center has been providing for decades is no longer possible”. The work is scheduled to be destroyed this year.

Composed of a curved boardwalk, a pavilion and other structures, all made of wood, concrete and common building materials, Greenwood Pond enables visitors to immerse themselves in nature, even descend to the water until they are at eye level with its surface. Miss has created such expansive works since the late 1960s that deepen human engagement with natural environments, including South Cove—an intimate esplanade at the tip of Manhattan—and Pool Complex: Orchard Valley, a playground-like structure in St Louis that reignites the site of an abandoned pool.

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond-Double Site, Des Moines, Iowa, in December 2023. Courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Public access to Greenwood Pond, which is on city-owned land, was suspended last October after the DMAC conducted a structural review. Its director Kelly Baum informed Miss then of the maintenance issues. Miss, based in New York, was travelling, so ensuing correspondence was limited, the artist tells The Art Newspaper. But she offered suggestions on ways to move forward with a full restoration, including reaching out to its original funders.

However, on 1 December, the DMAC told Miss that it had decided to deaccession Greenwood Pond. “I was shocked because there had been no further attempt to talk about this,” Miss says. “Even the initial conversation—‘What? All of a sudden, it’s deteriorated?’ It was completely out of the blue for me. I really thought we were going to have a conversation about possibilities.”

According to the Art Center, rebuilding the work would be “prohibitively expensive,” costing “many multiples of the original commission.” The institution also has a contract with the city that gives the city “the right to demand that the Art Center remove [a] work in question” should unsafe conditions develop. Representatives for the DMAC declined an interview request and did not respond to additional questions.

From its inception, Greenwood Pond was meant to be a permanent work. In the late 1980s, the DMAC invited Miss to Iowa for a site visit, and she learned about the issue of disappearing wetlands in the state. “This idea emerged of doing a demonstration wetland,” she says, “where people who lived in the city, who might not think about environmental issues, could have a more direct, more intimate experience with what lives in the wetland.”

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond-Double Site, Des Moines, Iowa, 1996. Photo © Mary Miss, courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation

From the work’s unveiling in 1996 until the early 2000s, museum staff gave her updates about its upkeep, she says. “But I don’t think that kept happening. There was not a maintenance schedule [anymore]. There just couldn’t have been, for it to get in this derelict state.” She adds that stewards of her other works constructed of the same wood, like Pool Complex, have managed to properly maintain those sites.

News of Greenwood Pond’s impending demolition has raised alarm among advocates of Land art, including the curator Leigh Arnold, who organised the recently closed exhibition Groundswell: Women of Land Art at Dallas’s Nasher Sculpture Center, which included Miss. “The lack of maintenance on this work, and the DMAC’s decision to destroy it, provoke important questions about responsibilities of stewardship and collection management,” Arnold says. “The Des Moines Art Center’s unwillingness to attempt to remediate the work in any way, whether in stages or all at once, is confounding given the importance of it and Miss’s stature as a leading artist in environmental installations.”

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), an education and advocacy organisation, is accusing the DMAC of possible contract violations with Miss. In commissioning Greenwood Pond, “the DMAC pledged to ‘reasonably protect and maintain’ the work,” says TCLF’s president and chief executive Charles A. Birnbaum. “The DMAC’s plan to tear down this widely hailed work is not only unreasonable, it undermines the Art Center’s fundamental role as a responsible steward of our shared cultural legacy.”

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond-Double Site, Des Moines, Iowa, in 2014. Photo © Sydney Royal Welch, courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation

TCLF, which monitors threatened landscapes in the US, had previously designated Greenwood Pond as “at-risk” in 2014, leading to fundraising efforts for a partial renovation that was completed the following year. Deemed “saved” over the last decade, the work is now again designated “at-risk”.

The uncertainty around the fate of her work has made it difficult for Miss to not see the problem as a reflection of gender disparities within the Land art movement, which has long privileged men as rightful explorers of “open” terrain. There’s an irony, she says, to seeing her work included in recent exhibitions that aim to correct this history, like Groundswell and 52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone at the Aldrich Museum (a revisit of Lucy Lippard’s 1971 landmark exhibition of women artists), while having to still fight for its existence elsewhere.

“Women artists who have been working with the land and thinking about the environment for a very long time—we haven’t been in the spotlight,” Miss says. “And for this to be the way that you resurface, it’s too bad. I think: Would this be happening the way it is now, if it was one of the men who's considered a master already?”