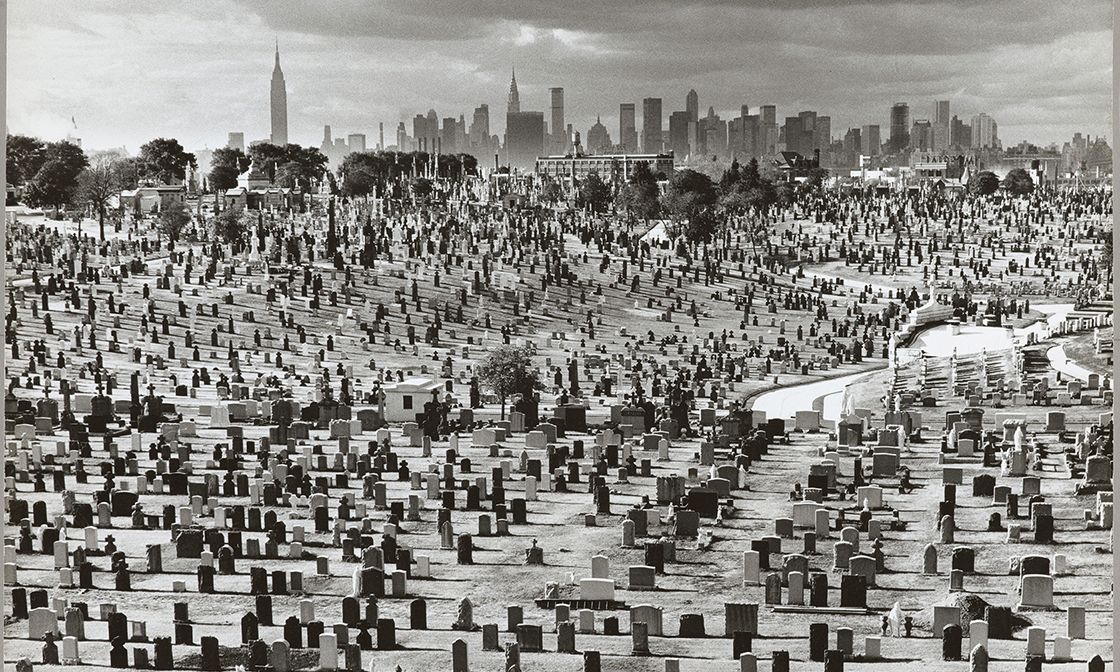

Arthur Tress’s Cemetery, Queens, New York (1969) featured in Life magazine in 1971

Courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum

“A photographer could be considered a kind of magician,” writes the US photographer Arthur Tress. “As a trained observer he can foretell the potential movements of his subjects and perhaps even by some mental intimidation […] actually cause them to happen.” Best known for his influence on the development of staged magical realism, Tress explores ideas of ritual, psychology and the pressures of economic and environmental hardship. Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows—which accompanies the current exhibition at the Getty Center in Los Angeles and authored by the Getty’s curators of photography—charts over six main chapters, alongside contributions by Tress himself via the preface and postscript, the development of the photographer’s style across the early part of his career. From poignant studies of the country’s Appalachian communities to the urban wreckages and disused spaces of New York, the publication reveals the emergence of Tress’s unique visual language, culminating in the dreamscapes and Surrealistic portraits of The Dream Collector (1972) and Theater of the Mind (1976), two early landmark series.

Born in Brooklyn in 1940, Tress demonstrated an early interest in photography while at school in Coney Island, before studying painting at the Bard College, New York, graduating in 1962. Following a period of extensive international travel—Europe, Japan, Africa, Mexico—Tress returned to the US in 1967, achieving commercial success with a number of documentary commissions. Typically photographing isolated rural communities, he travelled several times to Appalachia, including to North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, to record enduring handicraft and folk-art practices, set against a backdrop of post-war decline. Stately and measured, the photographs recall the Depression Era work of Edward Steichen (1879-1973) and the Farm Security Administration programme. More poignantly, perhaps, they speak directly to the legacy of Doris Ulmann (1882-1934), who photographed the same communities for Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands: A Book on Rural Arts (1937), which she would not live to see published; Tress discovered the book on his travels, taking it upon himself to track down Ulmann’s subjects, occasionally encountering their descendants and photographing them himself.

For the art critic and historian A. D. Coleman, an early champion of Tress’s work, the Appalachian photographs are “revelations of a lifestyle rapidly being shattered”, exposing the “disturbed” land of the country (to borrow the title of an early exhibition of Tress’s pictures at the Sierra Club in 1968). This “disturbance” is characteristic, also, of Tress’s city photographs of the late 1960s, exploring urban blight and overcrowding, focusing on the restrictive effects of New York’s claustrophobic built environments. In Open Space in the Inner City (around 1971), Tress’s subjects look exhausted, whether resting on the curb of a busy Fifth Avenue or pausing part-way up a flight of endless concrete steps, way out in the Bronx. In one picture, tired faces crowd the street, awaiting the start of a political rally; in another, two teenagers slump down on a stretch of dirty beach, their heads in their hands, a factory marking the horizon. “The American city is a cage and the smoke and ashes of civil disorder are the explosive efforts of the young trying to escape from its claustrophobic walls,” wrote Tress in an article accompanying his series. Appearing in an issue of Life magazine in 1971, the best-known picture from this series shows Manhattan rising gloomily above Calvary Cemetery in Queens, a labyrinth of scattered headstones, like a second city spreading silently beneath the first.

These photographs reveal the early signs of Tress’s interest in the uncanny, even sinister aspects of the American experience. In the 1970s, he began to explore explicitly psychological themes, focusing particularly on children’s dreams, producing a series of striking—if occasionally troubling—photographs of children in bizarre, surreal environments, apparently in distress or danger, though they seem eerily calm. Making frequent use of props and derelict spaces, directing his subjects to perform and improvise, Tress’s pictures in The Dream Collector disclose a recurring motif of entrapment: his subjects are constrained and buried, netted, trapped, engulfed, tied up or on the point of being grabbed by phantom hands (even pursued, in one frame, by a dinosaur). “Kidnapping Fantasy” shows a boy dragged slowly up a flight of stairs, a curtain tied around his neck. Another picture sees a teenager reclining in a coffin, feeling the last of the sun on his face, before the lid comes down, possibly for good. Ambiguous and oddly threatening, the dark, elusive symbolism of these photographs anticipates the arrival of the Surrealist filmmaker David Lynch, whose feature-length debut Eraserhead appeared in 1977. At the same time, Tress’s pictures recall the haunting images produced by the small-town photographer Charles Van Schaick (1852-1946), presented in Wisconsin Death Trip (1973). Published a year after The Dream Collector, Michael Lesy’s book curates a bizarre, macabre chronicle of incidents and newspaper reports from the turn of the century, an eerie analogue to Tress’s work.

Works such as Pearl Norwood, Maker of Raggedy Ann Dolls, Banner Elk, North Carolina (1968) demonstrate Arthur Tress’s continuation of the legacy of Depression-era photographers such as Doris Ullman

“Don’t be surprised if Arthur suddenly asks you to put your mother in a wheelbarrow,” writes the photographer Duane Michals of Tress’s habit for direction, “and don’t be amazed to find yourself doing it.” Tress becomes his own actor in Shadow (1975), “a novel in photographs”, in which he captures his own shadow in a range of tarot-like poses, evoking the imagery of German Expressionist cinema, particularly the claw-like, shadowed hand of F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922). Looking at the photographs in Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows, it comes as no surprise to discover the recurring presence of dolls and puppets in Tress’s work, revealing something of the way, perhaps, he views his human subjects, too.

The theatricality of Tress’s photographs reaches a peak in Theater of the Mind (1976), whose scenes explore relationships and the fragilities of the human body with stark humour and insight. Ed Berman and His Mother, Coney Island (1975) shows Berman holding an iron against his mother’s hand; Mrs Berman, in a quilted housecoat, looks on with curiosity, apparently feeling no pain, as if offering her hand deliberately. “Later when I sent him a copy of the print,” recalls Tress, “Ed told me it was right on as he could do whatever he wanted to do to his mother, and she never minded.” “In Tress’s hands the camera is an instrument with magical properties,” concludes the curator Paul Martineau in a new essay included here, “one that allows him to unearth our deepest secrets and put them on display.”

• Arthur Tress: Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows by James A. Ganz, Mazie M. Harris and Paul Martineau. J. Paul Getty Museum, 264pp, 17 colour and 198 b/w illustrations, $60/£50 (hb), published 21 November 2023

• Arthur Tress: Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows is at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, until 18 February