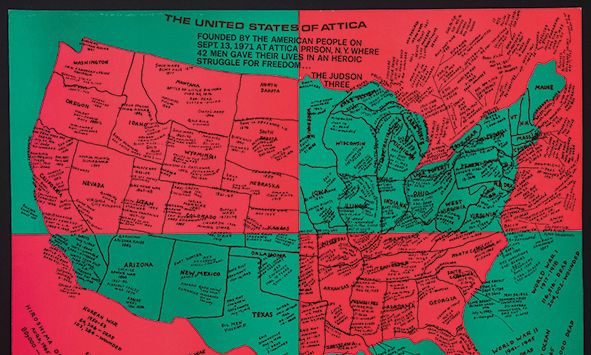

United States of Attica (1972) was part of Faith Ringgold’s show at the only museum with two entries in the year’s best/worst © Faith Ringgold/ARS and DACS; courtesy the artist and ACA Galleries

In terms of exhibitions, I doubt that there will be many better years in my lifetime than 2023. Among my highlights are some of the best shows I have ever seen—and there are many that narrowly missed the cut. Equally, I am not sure I will often be as dismayed as I was by my turkey of the year.

Matisse: The Red Studio, Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), Copenhagen

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio (1911) © 2021 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Although it opened in 2022, this was the first show that I saw in 2023 and it was a perfect exercise in exhibition-making. It reunited Matisse’s staggering 1911 masterpiece with the surviving works he depicts in it, along with additional pieces from two great Matisse collections: the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the SMK in Copenhagen.

Faith Ringgold: Black is Beautiful, Musée Picasso, Paris

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die (1967)

Slightly abridged from the 2022 New York show but still transcendent. The presence of Ringgold’s gut-wrenching Civil Rights tour de force, American People Series #20: Die (1967) in Paris, where Picasso painted the work that inspired it, Guernica (1937), encapsulated the exhibition’s emotional power.

Vermeer, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (1657-58)

A rare accurate use of the “once-in-a-lifetime” tag, this show managed to exceed expectations with its elegant staging, which somehow allowed for good sightlines amid the hordes. The artist Alvaro Barrington described it as one of the most profound experiences of his life; I can only agree.

Manet/Degas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Manet’s Le jambon (around 1875-80) © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Now on tour at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (until 7 January 2024), Manet/Degas is almost overwhelming in its scope—an inspired analysis of the two artists’ distinctive personalities, styles and approaches, as well as their common subjects and, ultimately, mutual greatness.

Carrie Mae Weems: Reflections for Now, Barbican Art Gallery, London

Carrie Mae Weems's Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Make Up) from the Kitchen Table Series (1990) © Carrie Mae Weems; Courtesy of the artist; Jack Shainman Gallery; New York / Galerie Barbara Thumm; Berlin

Weems’s first major UK museum show was beautifully paced, reflecting her journey from the magnificent photographs of The Kitchen Table Series (1990), through to the seven-act panoramic video installation The Shape of Things (2021), much of it shot through with both longing and defiance.

Chris Ofili: The Seven Deadly Sins, Victoria Miro Gallery, London

Chris Ofili, The Pink Waterfall (detail, 2019–2023) © Chris Ofili Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Ofili’s seven-painting opus is his finest achievement yet. Bringing the sensuous, luminous language he has developed since his move to Trinidad to new extremes, the sequence is full of potent flora and mythical fauna but gives no easy answers to whether sin is something to be resisted or embraced.

Claudette Johnson: Presence, The Courtauld, London (until 14 January 2024)

Claudette Johnson, Kind of Blue (2020) Photo: Andy Keate; © Claudette Johnson; Image courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

Another long overdue first London museum show, reflecting the extraordinary sureness in Johnson’s exploration of the Black female figure in her early work, much of it made at art school, and her scintillating return to form after a long impasse between the 1990s and 2014.

Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, Tate Britain, London (until 14 January 2024)

An installation view of Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas at Tate Britain © Sarah Lucas. Photo: Tate (Lucy Green)

One of those surveys you feel an artist has been leading up to for years. The consummate expression of her uncompromising, unorthodox, off-kilter sensibility, retaining an astonishing directness and rawness from her earliest 1990s work to today.

Philip Guston, Tate Modern, London (until 25 February 2024)

Guston's anti-war painting Bombardment (1937) Photo: © Tate (Larina Fernandes)

Long awaited but magnificent, Tate Modern’s version of the controversially postponed show was flawless bar the curious omission of some of Guston’s darkest 1970s masterpieces. It explains Guston’s life and work with exemplary clearness and sensitivity, while deepening his paintings’ inherent mysteries.

The turkey: Picasso Celebration, Musée Picasso, Paris

An installation view of Picasso Celebration © Musée National Picasso-Paris, Voyez-Vous (Vinciane Lebrun) and Succession Picasso 2023

What a terrible way to mark the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death. Paul Smith was given carte blanche to redesign the museum’s displays, and delivered an abysmal rehang, aiming for visual enhancement but destroying the works with decorative mayhem.