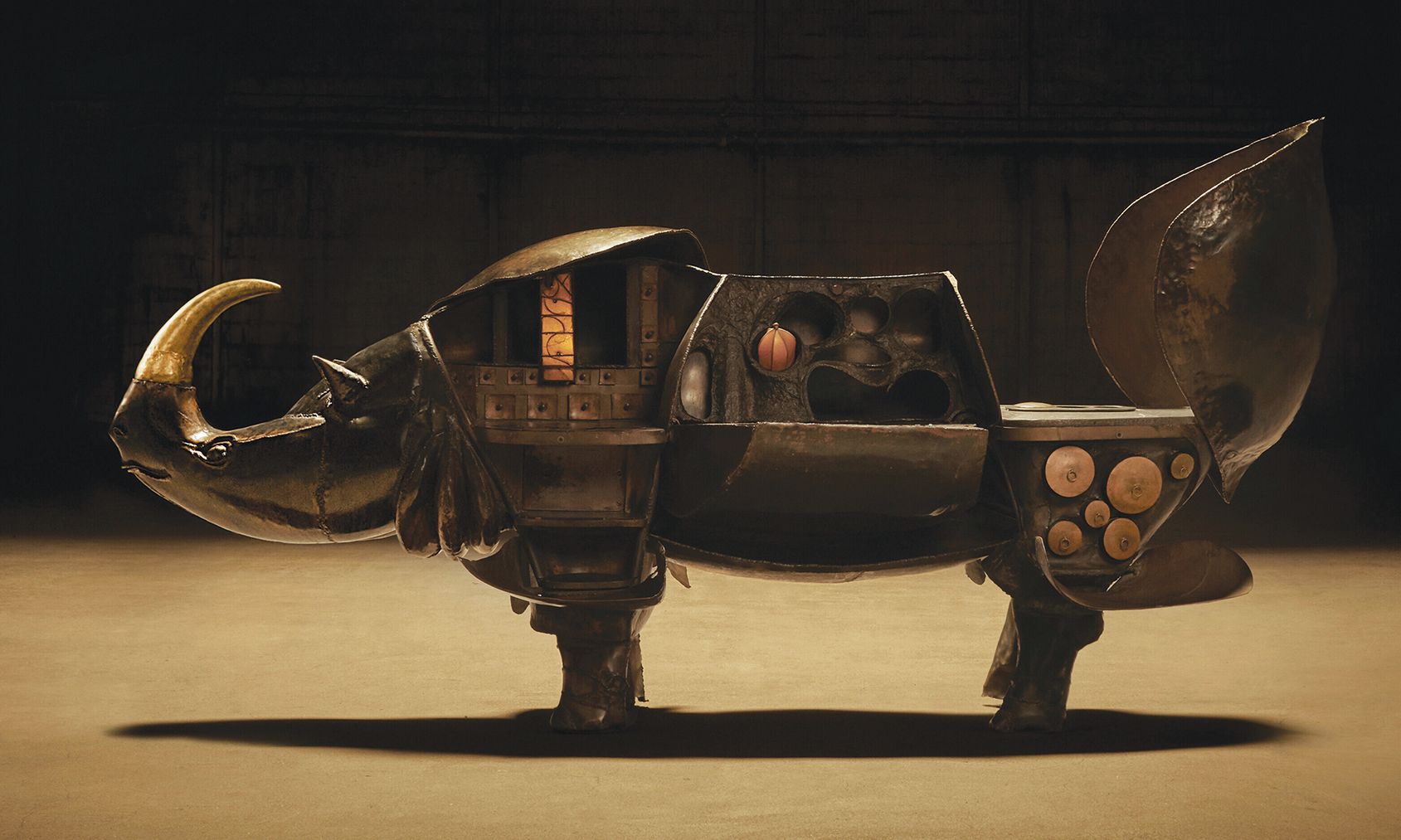

Beast with a bar: François-Xavier Lalanne’s Rhinocrétaire I (below) sold at Christie’s Paris last month for €18.3m Courtesy of Christie’s

The market for Les Lalanne, the French husband-and-wife duo known for their whimsical, surreal sculptures of animals and plants, has never been stronger. While the record-setting €18.3m sale of a historic work at Christie’s Paris on 20 October reflects the vital link between the artists and their native France, insiders say the demand for their output is global. “The Lalanne market knows no borders. It really is collected by every community and culture,” says Edith Dicconson, the executive director of New York’s Kasmin gallery, which has represented François-Xavier (1927-2008) and Claude (1925-2019) Lalanne in the US since 2007.

The piece sold at Christie’s, Rhinocrétaire I (1964), is a brass rhinoceros housing a desk, safe, bar and wine storage in hidden compartments. It was the first sculpture François-Xavier is known to have created after retiring from painting in 1963. He had participated in just one exhibition, in Paris in 1953, before turning his back on the medium. He told Vogue magazine in 1966 that “painting is done for”.

At his lone painting show, however, François-Xavier met Claude, the daughter of a gold broker and a musician, who would become his partner in art and life. Rhinocrétaire I was included in Zoophites, the duo’s first joint exhibition, held at Galerie J. in Paris in 1964.

“This is the manifest of François-Xavier Lalanne, and it’s crazy to see such a first work being so important within his career,” says Agathe de Bazin, head of design sales for Christie’s in Paris.

In 1966, Greek-American dealer Alexander Iolas showed François-Xavier and Claude alongside Surrealists like Max Ernst and René Magritte in an exhibition that helped put Les Lalanne “on the map”, Dicconson says. It also helped contextualise their sculptures. Although the works could be (and often still are) misconstrued as intellectually lightweight, they were informed by the “Surrealist idea of the radical juxtaposition, the opposite of form follows function”, says Nick Olney, the president of Kasmin.

“It’s having something that looks like a rhinoceros but then unfolds and becomes all of these other amazing things in a bar. You get this sort of cognitive dissonance but also joy when you start to experience them,” he adds.

This theme is common in the output of François-Xavier and Claude, whether working together or separately. The most recognisable works from either may be François-Xavier’s Mouton sculptures, life-sized sheep made from varying materials that he intended to be shown indoors to “create something very invasive… like bringing the countryside to Paris”, as he put it.

François-Xavier Lalanne created numerous sheep during his career, including this group, which sold at Bonhams in New York in July Courtesy of Bonhams

“I call the sheep the gateway drug,” Dicconson says, adding that new clients often buy a Mouton sculpture before falling in love with “the world of Lalanne”. Kasmin will try to induce more such love in April 2024 by opening a major show of the duo’s works curated by Paul B. Franklin from the collection of their daughter Caroline Hamisky Lalanne.

Les Lalanne have had a strong French market, as well as some active American collectors, since their early days, de Bazin of Christie’s says. A 1967 show at the Art Institute of Chicago helped anchor the couple’s reputation in the US. The Lalannes took part in exhibitions internationally throughout the following decades, and Iolas placed their work with such prestigious collectors as the French branch of the Rothschild banking family, British art collector Pauline Karpidas and Gianni Agnelli, the former head of Fiat.

Three years after Iolas’s death in 1987, the Lalannes began working with France’s Galerie Mitterrand, founded by their friend Jean-Gabriel Mitterrand. The dealer Ben Brown, who began representing the duo in London in 2004, significantly grew their market by introducing their work to Asia (his gallery expanded to Hong Kong in 2009) and featuring it at major events like The European Fine Art Fair (Tefaf) in Maastricht and New York. Brown says he also “brought Paul Kasmin into the network at the very beginning, as I knew that without New York and America, we would never succeed in bringing their market up to a level which they deserved”.

Brown frames the three dealers’ championing of Les Lalanne in the fine art world as an important bulwark against their works’ regular inclusion in decorative art auctions, a decision he labels “obviously absurd and the main reason why Claude and François never liked the auction houses”.

And yet, arguably the biggest turning point in Les Lalanne’s commercial trajectory came in 2009: Christie’s auction of the personal collection of fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent and his partner, Pierre Bergé, in Paris. It became the most valuable collection ever sold at auction at that date, racking up €373.9m in the depths of the Great Recession, with two commissioned Lalanne works in particular reaching what Olney calls “big, eye-opening, public numbers”: the Bar ‘YSL’ (1965), by François-Xavier, sold for €2.8m; and mirrors from the installation Salon des Miroirs (1974-85), by Claude, sold for €1.9m. The same year, Kasmin enjoyed a major hit by staging a massive outdoor installation of François-Xavier’s Mouton on New York’s Park Avenue.

Demand for the artists’ output has only grown since. “Basically, you can just add a zero to the price of any of their works now compared with when I started working with them,” Brown said in 2019. Four years later, he deems it “arguably easier to sell their work now [that] it is very expensive than it was when the prices were more reasonable”.

The collector pool for Les Lalanne is evenly split by region today, sellers say. Christie’s data show that roughly one-third of its Lalanne buyers are based in the US, one-third in Europe and one-third in Asia, with a small number elsewhere. Olney notes Kasmin has sold works to important collections in Central and South America.

Demand for Claude’s solo pieces, often featuring playful flora and distinctive metalwork, has particularly grown in the past 15 years, Olney says. Her avant-garde jewellery, including pieces made for such fashion houses as Dior and Saint Laurent, has influenced generations of designers. Her Choupatte sculptures, of cabbage heads with chicken feet made in patinated and galvanised copper, exemplify her craftsmanship and broad appeal.

Yet Claude’s work still trails that of François-Xavier commercially; her record under the hammer is €3.7m (with fees), for a 2003 butterfly chandelier sold at Christie’s Paris in 2021, almost five times less than François-Xavier’s new auction apex of €18.3m for Rhinocrétaire I. The highest price achieved for a collaboration by the couple is €4.5m, for a hybrid sculpture combining one of Claude’s apples topped by one of François-Xavier’s monkeys, at Sotheby’s Paris in 2021.

François-Xavier’s death in 2008 further boosted his profile and market. Claude remained active in organising exhibitions for both her and her husband’s art, as well as in creating new work, until shortly before her death at age 93 in 2019. Months later, the family’s estate sale at Sotheby’s Paris fetched €91.3m (with fees), quadrupling the auction house’s high estimate. Buyers from 43 countries snapped up all 274 lots on offer.

Despite Les Lalanne’s global charm, selling the work in Paris still has a certain draw for collectors, de Bazin says. Rhinocrétaire I was consigned in the spring of this year and did not need to be sold urgently, allowing Christie’s time to perfect its strategy. The auction house arranged to sell it in Paris this October to align with the art world’s convergence on the city for the second Paris+ by Art Basel fair.

In early October, the sale of 19 additional lots from the Lalanne estate at Sotheby’s Paris more than doubled the low estimate, fetching nearly €8.2m (with fees). Sotheby’s also expected to make up to €11m (before fees) from 31 Lalanne works in the sale of art and design objects from the Karpidas collection in Paris on 30-31 October (after The Art Newspaper went to print). In fact, a Sotheby’s spokesperson previously cited the strength of her Lalanne collection (which Brown calls “certainly one of the best in the world”) as the primary reason the house prompted some shock in Britain by staging the auction in Paris, rather than London.

“There is a strong link between Paris and Lalanne,” de Bazin of Christie’s says. “It tells the story of a French artistic world. And we know this rings a bell for collectors.”