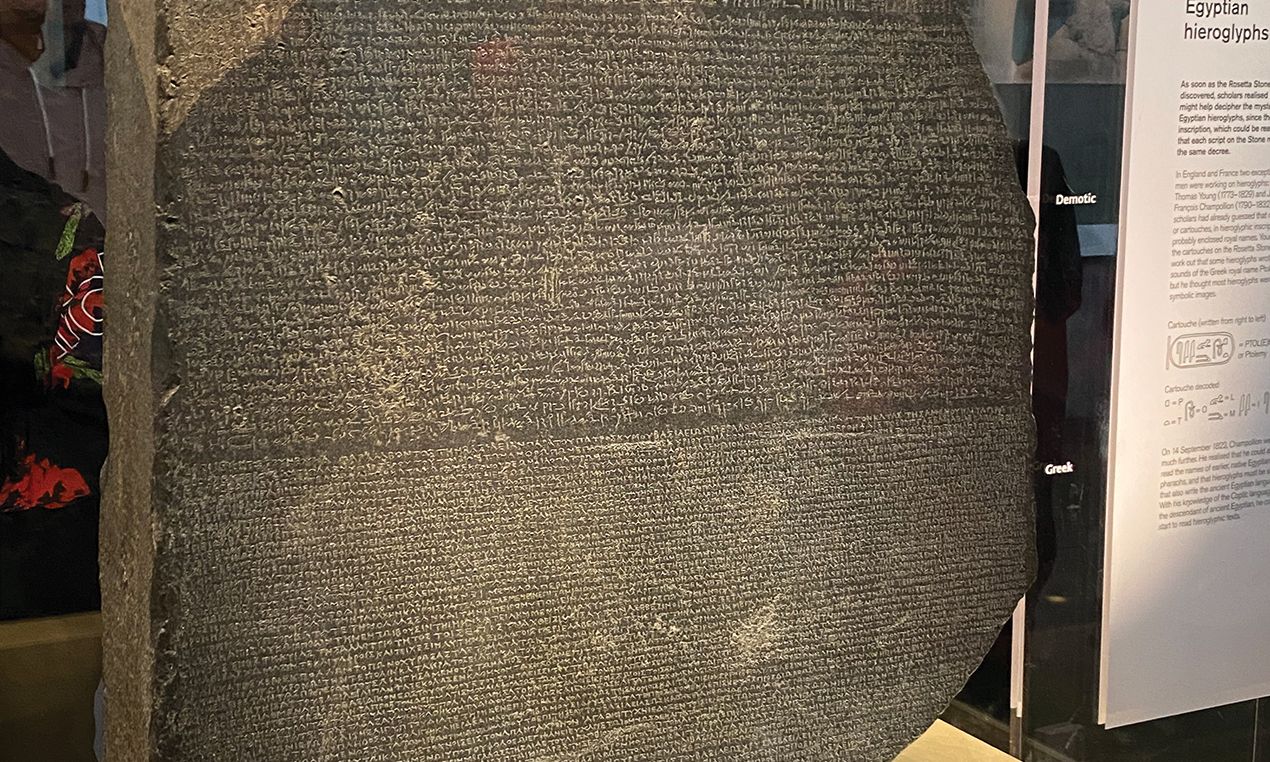

Using new technology, the collective Looty carried out a “daring digital heist” at the British Museum in order to “return” the Rosetta Stone to Egypt © EWY Media

One hopes not to find loot at an art fair these days, but at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London in October, one of the stands was focused on just such objects. The collective Looty uses digital technologies to increase accessibility to art and heritage, and at 1-54 it presented its project Return Rashid! (2023), in which the group “executed a daring digital heist at the British Museum”. Their target was the Rosetta Stone—originally known as the Hajar Rashid—which was taken from Rashid, Egypt, by the French in 1799 and later handed over to the British by the defeated French in a surrender deal. Looty utilised light detection and ranging (Lidar) technology to record detailed scans of the tablet, and the resulting 3D renderings were then used alongside a geolocation-based augmented reality (AR) platform to place the digital object in Rashid. “This innovative use of technology allowed for one of the world’s first-ever digitally repatriated artworks to be placed back in its original physical realm,” Looty says on its website.

While the stunt was a headline-grabbing challenge to the British Museum, which is not allowed to restitute its holdings (the museum declined a request to comment for this article), is the act truly groundbreaking? Could rapidly developing technologies like AR, artificial intelligence (AI), NFTs (non-fungible tokens) and 3D scanning help solve some of the fractious issues around contested physical objects and the campaigns for them to be returned?

“I think 1,000% digital technology can play a part in restitution,” says Chidi Nwaubani, the British Nigerian founder of Looty. “One of the most important things is that the laws have not caught up with society yet, in terms of digital artefacts and ownership of digital things. With Looty, we wanted to be the first people to set the mandate and a precedent on this.”

But many lawyers within the field argue that greater caution is needed, particularly with artefacts that are contested. “Digitisation is not neutral,” says Andrea Wallace, an associate professor at the University of Exeter Law School in England. “Depending on the physical location where you digitise something, all of the laws of that jurisdiction are going to attach to every part of that process,” she explains, arguing that we must find ways to support restitution “without replicating the colonial logic and systems that we’re trying to disentangle in the first place”.

One positive use of technology in the field of restitution is in the creation of digital databases. “Increased efforts by museums to provide 2D digital images of their collections, both directly to communities and by posting them online for the broader public, has rapidly expanded the ability of source communities to know what is held by museums. This is a critical first step,” says Eric Hollinger, the tribal liaison for the repatriation programme at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, DC.

Piotr Stec, a professor and the director of the Institute of Legal Studies at the University of Opole in Poland, suggests that technology can help map the processes of an object’s transfer and assess a restitution claim’s legal and ethical validity. “Technology may help to identify the paper trail: the history of legal and sometimes not-so-legal or completely illegal cultural property transfers,” he says. The German-led Digital Benin project, mapping and documenting the objects taken from the Kingdom of Benin—now in modern-day Nigeria—is often cited as an example of good practice within heritage digitisation and restitution.

But in the rush to digitise collections, and often to make them open-access, Wallace says, the communities to which many museum objects belong are not being consulted. “We’re starting to see how [digitisation] can actually be violent in and of itself because [these objects] could be someone’s ancestor or a sacred object, or be considered as having a personhood or spirithood,” she says. “Institutions are making decisions on behalf of others about who is able to use or access the works online.” The surge of AI usage also poses a problem. As with artists’ images of works, photographs of historical objects and heritage on the internet are prone to data mining and use in open-source AI programs in often unethical and biased ways.

Advancements in 3D scanning mean practically anyone can do it—many of the latest iPhone models now have the Lidar sensors that Looty used to copy the Rosetta Stone. More and more of these objects are being made available on open-source asset platforms such as Sketchfab.

Pinar Oruc, a lecturer in commercial law at the University of Manchester, England, argues that 3D printing has greater use in preservation and education than in restitution. She says that high-quality casts of the Parthenon Marbles that are held in the British Museum, for example, have been possible for hundreds of years, and have not stopped Greece from demanding the return of the originals. “So far, I haven’t seen anyone saying that copies are enough for them and that they’re going to stop asking for restitution. If anything, it could be somewhat insensitive to offer only copies,” Oruc says. The NMNH has worked with Indigenous tribes for more than 15 years using 3D technology in the context of restitution, often returning original artefacts and retaining 3D printed copies.

Speaking of nations’ desires to own original objects, Alex Herman, the director of the UK-based Institute of Art and Law, says that “a cult of the ‘real’ can be a problem” in debates around creating copies. Hollinger, however, thinks that the “aura” of the real is becoming less of a differentiation. “People are viewing images of things and places through their digital devices and I think that is influencing how they perceive [things] when they view a physical object or a surrogate of that object,” he says.

Some believe that NFTs could bring “uniqueness” to digital objects or copies. Looty uses NFTs to authenticate its 3D renderings of historical artefacts, like the Benin Bronzes. “It’s the best technology for us to use when it comes to ensuring the provenance of artefacts,” Nwaubani says. “It also allows for royalties to be paid out. You can have a digital artefact that is owned by Nigeria and is put in circulation around the world for everybody to enjoy with royalties for its use being directly paid to the owner,” he says. These can be set with smart contracts on the blockchain to ensure payouts.

Earlier this year Stec wrote a paper proposing a working model for what he calls “e-restitution”. In it, the two interested parties of a contested object share ownership that is based on a division of rights and responsibilities. One would hold the physical object and the other its digital representation certified with an NFT. “The returning country would be entitled to use an object in the way it has been used by a museum so far. This mainly refers to the right to own, possess, research and exhibit an object. The returning country would also be responsible for the safekeeping and maintenance of an object. The country of origin will have legal title and the right to exploit an object online, and to use it in all the manners not covered by the rights of the returning country,” Stec explains.

But many doubt the credibility of NFTs. “The NFT market isn’t what it used to be. I think it might be a dangerous market to associate with right now,” Herman says. “If the platforms aren’t around because they all go under next year, then what happens to your NFT? The longevity and sustainability of it is questionable.”

Most people agree that technology can play a role in restitution debates. Its main use lies in its ability to make the first step in negotiations. “Technology opens up new possibilities for establishing and then building relationships between an institution that holds property and a claimant,” Herman says. “From that, I think more serious discussions around restitution, in the physical sense, can take place.”

But, as Wallace argues, greater collaboration is needed from the side of objects’ original owners to ensure that legal, ethical and useful digitisation is taking place. “I think it’s important to slow down and think critically in this area so that we ask the right questions and we put people in the position where they provide the answers, rather than us trying to solve it,” she says. Stec agrees that “empirical data on how post-colonial and post-dependency communities perceive digital restitution is needed”.

In the meantime, artists and activists like Looty will continue to push the boundaries with their use of technology. Besides anything else, such projects raise awareness of the issues around restitution, particularly reaching a younger, more digitally native, audience. “These are not mere exhibitions; they are dialogues, conversations that invite participation, introspection and, ultimately, transformation,” Looty says on its website. They conclude: “Current debates rage endlessly around whether artefacts should be physically returned; Looty have taken matters into their own hands.”