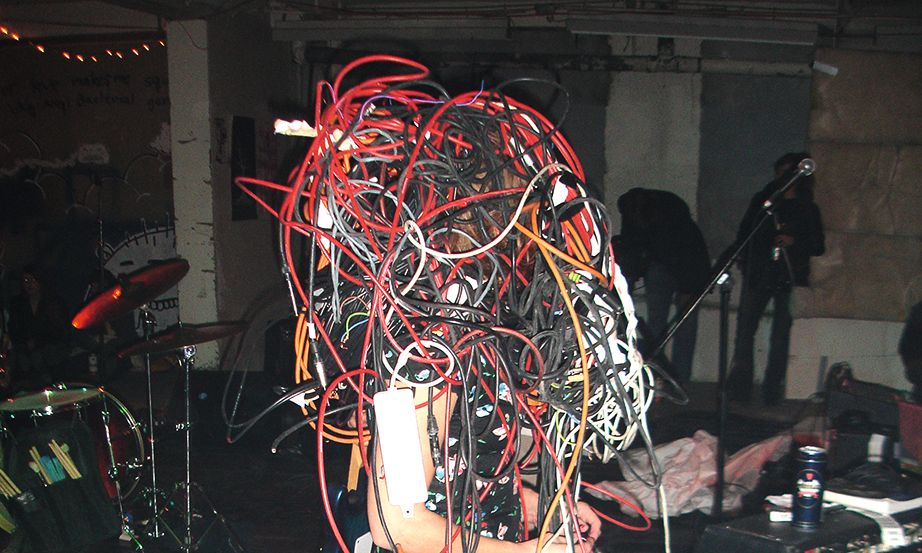

“Everyone into art in Reykjavik was there”: Björk was one of the regulars at Klink and Bank

© Guðmundur Oddur Magnússon, courtesy Kling og Bang

Twenty years ago, in November 2003, the National Bank of Iceland made contact with a new gallery space called Kling & Bang, an emerging contemporary art venue in Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik.

Kling & Bang was founded earlier that year when ten local artists clubbed together to open a small exhibition space on Laugavegur in downtown Reykjavik. “There was no platform, no opportunity for young or emerging artists to exhibit,” says Erling Klingenberg, one of the founding members. “We opened the gallery in order to change that.”

The city’s small circle of financial workers were evidently impressed. The National Bank of Iceland wanted to support the gallery, with its name on it—but how? The artists convinced the bank to convert a huge, unused industrial building—a former fish-net factory—which stood empty, a stone’s throw from the gallery. They divided the 5,000 sq. m “artist base”, as they called it, into a myriad of studio, exhibition and performance spaces. In all, 137 artists, designers, film-makers and musicians worked in the building on a day-to-day basis. They called it Klink and Bank—“klink” being a slang word for poverty in Iceland. “Their only proviso was we had to run it responsibly,” Klingenberg says, with a wink.

Klink and Bank was a renowned arts space where 137 artists, designers, film-makers and musicians worked on a wide variety of projects

© Guðmundur Oddur Magnússon, courtesy Kling og Bang

The project was a petri dish for an art ecosystem that soon went global, turning a tiny city on one of the most isolated islands in the Atlantic ocean into a byword for multi-disciplinary art. “Everyone was so happy to be a part of it,” Klingenberg says. “We had experimental theatre, installations, musicians, designers, raves—all the art you can think of, on a daily basis. Everyone into art in Reykjavik was there. And artists just began to collaborate, automatically, across disciplines. It had so much effect.”

“We decided early on that we didn’t want to be underground,” says Hekla Dögg Jónsdóttir, an original founder of Klink and Bank and now a professor of fine art at the Iceland University of the Arts. “We wanted to reach out.”

Ragnar Kjartansson, one of Iceland’s best-known artists, cut his teeth there while Icelandic superstar Björk was a regular attendee. The post-rock band Sigur Rós had their first performances in the basement of the building.

“Kjartansson was born in this building,” says Guðmundur Oddur Magnússon, a fellow founder and also now a professor at the Iceland University of the Arts. “Ragnar got his gallery in New York after a visitor saw him doing his earliest performances in Klink and Bank. We all just knew him as a student who was trying some things out. We all just thought he was a wannabe pop star.”

Jónsdóttir studied art at the California Institute of the Arts in the US and retained contacts there. Klink and Bank began, as a result, to spread around Californian circles. “The space became a way for us to have contact with artists from America and Europe,” she says.

At the time Reykjavik had a population of less than 120,000, but the nightly mash up of creativity at Klink and Bank spread, soon gaining a mythic status in the art world. Foreign artists wanted in; within two years of opening, the Californian artist Paul McCarthy exhibited there, as did the German artist John Bock. The Canadian electro act Peaches performed there. Lou Reed of the Velvet Underground was a visitor.

Klink and Bank grew almost too quickly. “We were constantly having to work out how to run the place, given it remained a volunteer-led initiative,” Jónsdóttir says. “It was tricky.”

It became a graffiti-covered warren that often coupled as a de facto club for the city’s ravers. “After a late night, we often didn’t know who had taken the keys to the gallery,” Klingenberg says. With little hierarchy, the upkeep started to become an issue. Within just two years, the founding members began to feel they had lost control of the venue and moved on to other ventures. The building continued to be used by other artists in a haphazard way, but it fell increasingly into a state of disrepair and anarchy. The building was demolished in the autumn of 2006, by then derelict.

“It was a great time, it was fun, but a lot happened,” Klingenberg says. “We became exhausted by it. And then the building just went.”

On 6 October 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, Iceland’s prime minister Geir Haarde gave a speech that ended with a phrase often referenced by Icelanders today: “God Bless Iceland.” Haarde announced that all three of the country’s major privately owned commercial banks had defaulted. Iceland’s government was unable to find a way to recapitalise, and billions of pounds’ worth of assets in effect disappeared.

The aftermath of the banking crisis is still felt in Iceland today. While tourism, especially from the US, has become fundamental to the island’s economy, the state still struggles to allocate its meagre resources on culture, while the country’s financial services no longer support art.

The ground on which Klink and Bank once existed has been converted, unsurprisingly, into hotels. Kling & Bang continues to exist, in a smaller gallery housed in a former herring factory in Reykjavik’s still-working harbour.

Last month, the founding of Kling & Bang was marked, 20 years on, by its founders as they exhibited as part of the 11th edition of Sequences, Reykjavik’s contemporary art biennial. Klingenberg says: “The building is long gone, but the network and the culture remain.” Magnússon adds: “They carried on, extending out into the world.”