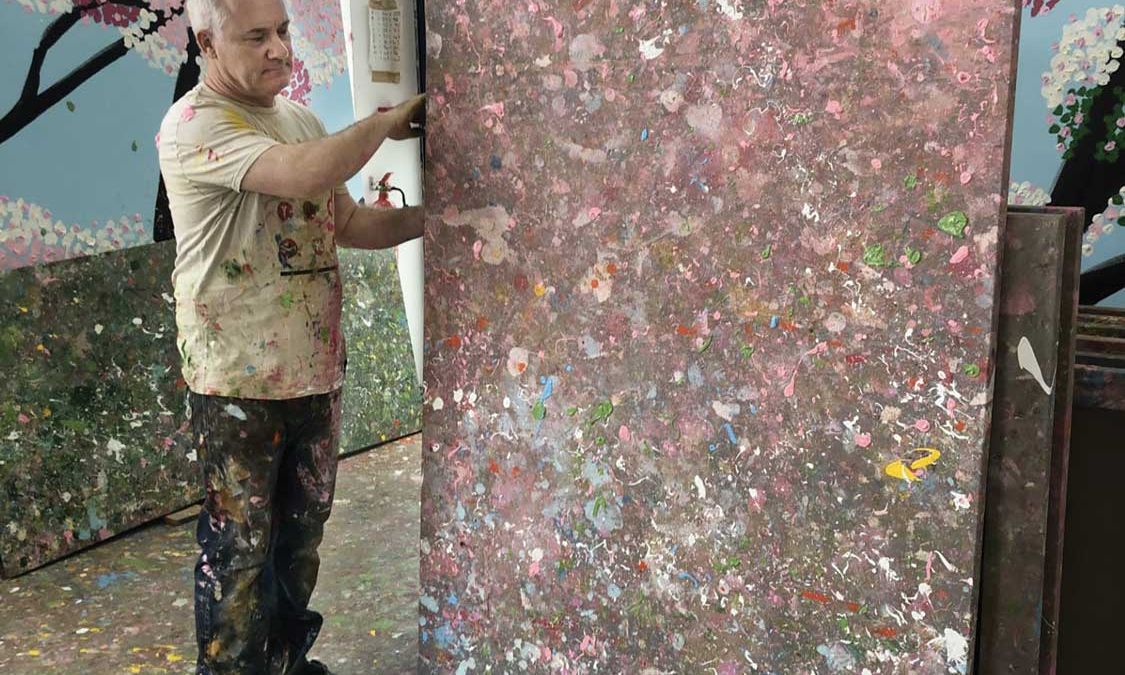

Damien Hirst’s 2019 Coast Paintings were included in Where the Land Meets the Sea, a private selling exhibition staged in partnership with Phillips

© Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved; DACS/Artmage 2023

Damien Hirst has always taken his career into his own hands. “With art I think part of my success has been that I don’t believe there are any rules…” he writes in an Instagram post from July promoting what was then his latest venture: Where the Land Meets the Sea, a private selling exhibition of 102 new works from three series held at Phillips auction house in London the same month.

Phillips was the “exhibition partner” for the show, while the paintings (priced between $100,000 and $1.3m) were available through HENI Primary, a recent addition to the HENI group through which artists sell works directly to collectors. HENI’s founder, the lawyer Joe Hage, manages Hirst alongside other living artists, including Peter Doig and Gerhard Richter. A spokesperson for Hirst declined to comment on sales, which were also fielded through the artist’s galleries, Gagosian and White Cube.

It was a very different picture 15 years ago, when Hirst bypassed his dealers altogether to sell 223 works fresh from his studio in Beautiful Inside My Head Forever, that fêted 2008 auction at Sotheby’s in London. “Damien was a trailblazer. It was a highly controversial move,” says Cheyenne Westphal, Phillips’s global chairman, who worked at Sotheby’s at the time.

Hirst’s dealers responded in their own ways. Larry Gagosian hosted a group exhibition of gallery artists—pointedly excluding Hirst—at the Red October Chocolate Factory in Moscow at the same time as Sotheby’s launched its pre-sale show in London. White Cube’s Jay Jopling attended the sale in person, bidding on several lots and winning at least one, The Triumvirate (2008), for £1.7m. Overall, the auction raked in £111.4m over two days, just as Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in New York and global stock markets imploded.

“The established gallery model was truly shaken up in a way that has reshaped the dynamics between the different players in the market,” says Oliver Barker, Sotheby’s chairman in Europe, who was on the rostrum for the sale. He notes how Hirst has always maintained his own dialogue with his collectors, including buying back 12 works in 2003 for an undisclosed sum from his first patron, the advertising mogul Charles Saatchi.

Since 2008, Sotheby’s has worked with other artists keen to operate outside conventional primary-market structures, including Banksy, who rejects gallery representation and instead consigns works straight from his studio. Like Hirst, Banksy is prone to creating works that double as provocations to the old market order, notably shredding one of his own paintings during a live auction at Sotheby’s London in October 2018, then authenticating the scraps as a new piece, called Love Is in the Bin.

Other artists besides Hirst are working directly with Phillips. Of the house’s 14 private selling exhibitions in 2022, eight featured primary works; seven of the 20 private selling shows it plans to hold in 2023 will do the same, including Hirst’s.

Auction houses have experimented with the primary market in other ways, too. In its September 2022 Contemporary Curated sale in New York, Sotheby’s launched Artist’s Choice, an initiative through which the house auctions works consigned jointly from artists and their galleries. (No further Artist’s Choice sales have been held since.) Also last September, Christie’s offered six primary-market pieces by Black artists, consigned by the Baltimore-based Galerie Myrtis, as a part of its Post-war to the Present auction.

This August, meanwhile, Phillips launched Dropshop, a digital platform offering monthly releases of newly commissioned, limited-edition art and objects designed to be, in Westphal’s words, “a very quick and easy buying experience”. Artists also receive 3% from future resales—if the work is resold through Phillips. “We are very much looking at maintaining ongoing relationships with the artists and their communities,” she says.

Notably, each of the major auction houses made these recent moves after spending more than a year auctioning NFTs (non-fungible tokens), often consigned directly from digital artists, either in standalone sales or alongside more traditional secondary-market pieces in their usual auctions. Sotheby’s and Phillips were quick to embrace the model once Christie’s racked up $69.3m (with fees) for Beeple’s Everydays—the First 5000 Days (2021) in an online sale in March 2021.

Simon de Pury, the Swiss auctioneer and dealer, began offering primary-market works through his auction platform, called de Pury, back in August 2022. He notes how galleries’ tightly controlling access to new works has led to “spikes in prices for red-hot artists” at auction. The main beneficiaries of these auction sales, he adds, are the collectors “who have been lucky enough to acquire these works on the primary market”, not the artists nor the galleries “who champion them”. His model aims to reverse that imbalance.

De Pury thinks the “top five galleries with locations around the world” will soon stage their own auctions, particularly if art fair sales continue to slide. “They are just as well placed to sell these in-demand works at auction. They know exactly who the potential buyers are,” he says. Organising auctions is also easier and cheaper than ever, he adds, since the Covid-19 era proved “the vast majority” of buyers bid without ever seeing the works in person.

Galleries are already experimenting with the auction format through charitable initiatives. In December 2022, Hauser & Wirth held an online auction of works donated by artists to fundraise for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. This May, Pace Gallery teamed up with Sotheby’s for an auction benefiting the Nina Simone Childhood Home preservation project.

With primary and secondary markets blurring into one another and auction seasons bleeding into year-round sales, the old lines between artists, galleries and auction houses are being redrawn rather than completely erased. As Westphal puts it: “It’s not wholesale change but an enlivening of the whole infrastructure.”