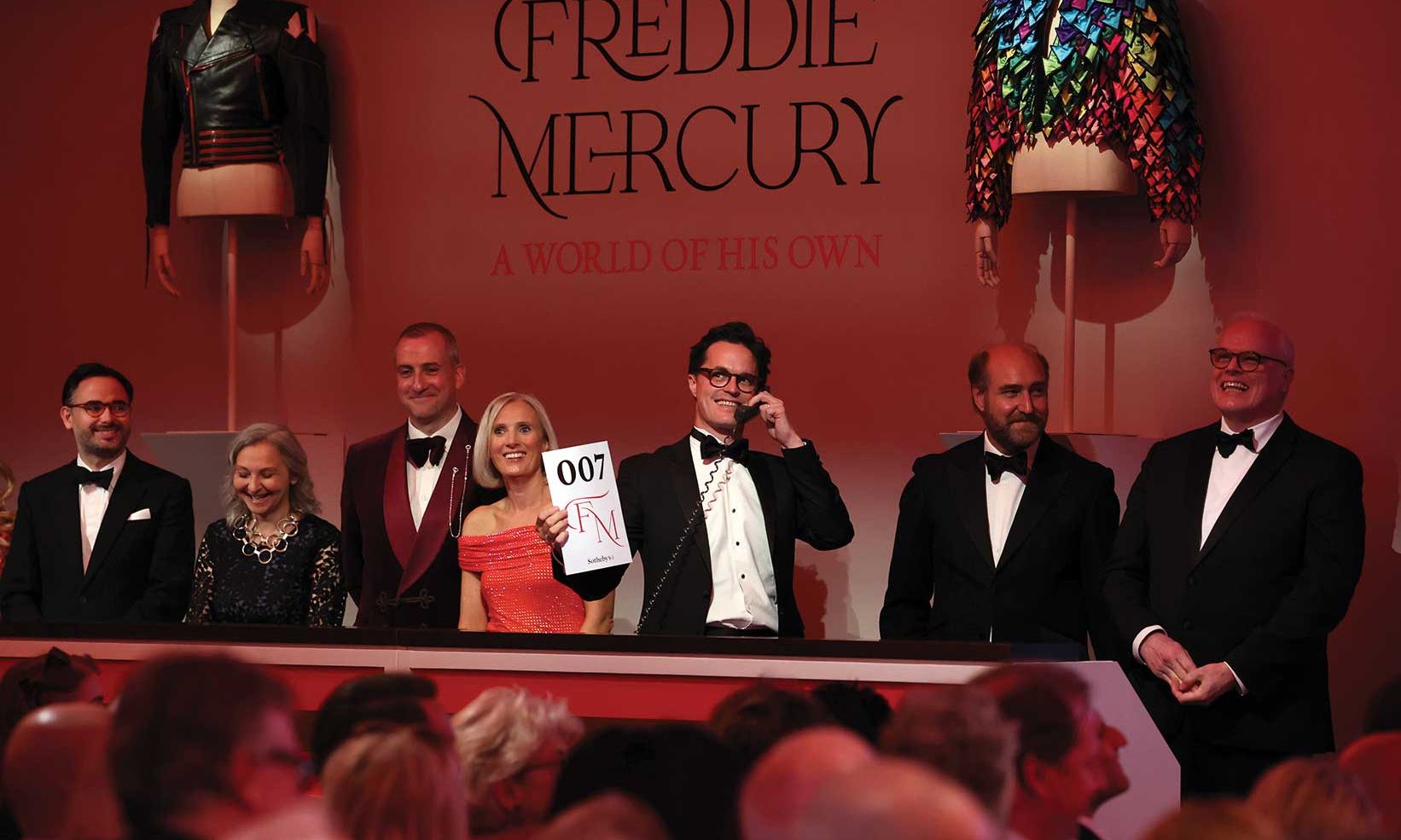

“White glove” sale: Sotheby’s London auction on 6 September, Freddie Mercury: A World of His Own, totalled £12.2m (with fees), with all 59 lots sold

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby’s

It was billed as Freddie Mercury: A World of His Own. Prices at Sotheby’s 6 September evening sale of the Queen frontman’s personal collection in London were certainly in a league of their own. The auction totalled £12.2m (with fees), obliterating the low estimate of £4.8m (without fees). Bidders had gone “wild”, stated Sotheby’s in its post-sale press release, and “every single one” of the 59 lots “found a buyer”. The bidding process for each lot was enthusiastically applauded by the champagne-sipping audience of more than 400, most of whom were middle-aged Queen fans who had never been to a Sotheby’s auction before.

So-called “white glove” sales, in which all lots successfully find a buyer, used to be a rarity at auction. But now, thanks to mechanisms like guaranteed minimum prices and the last-minute withdrawal of big-ticket lots that attract insufficient pre-sale interest, they have almost become the norm for evening sales of prestigious named collections. Increasingly, the risk is too great for the houses to leave the outcome up to live bidders. Failure to achieve this 100% selling rate, particularly if a high-value lot is the one to flop, could give the wrong impression to future consignors.

This appears to have been what was at stake after Sotheby’s specialists seemed to seriously over-estimate the star lot of their glitzy sale. At the 11th hour, the auction house announced Mercury’s 1973 Yamaha baby grand piano, on which he composed “Bohemian Rhapsody” and other hits, would be offered “without reserve”, meaning it would sell even if the highest bid was nowhere near its ambitious low estimate of £2m. No piano had ever sold for such a steep price at a public auction.

A Sotheby’s spokesperson said the collection’s seller, Mercury’s lifelong friend Mary Austin, wanted to remove the reserve price “to open the possibility of bidding to a broader base of potential buyers”. But do populism and the desire for the piano to go to, in Austin’s words, “a home where it will be loved, cherished and enjoyed to the full” sound like a more plausible explanation for the price drop than the auction house’s fear of the top lot failing?

With the bidding opening at just £40,000, there was a predictable flurry of raised paddles in the room, followed by a stream of internet and telephone bids. But once the price reached seven figures, competition noticeably thinned, and the virtuoso auctioneer Oliver Barker ultimately knocked down the piano to a final bid of £1.4m from an online client. Even after the addition of Sotheby’s hefty premiums, the final price totalled slightly more than £1.7m, well beneath the £2m low estimate and quite probably beneath the reserve had it not been eliminated.

“I thought the estimate was a bit strong,” says Tony Bingham, a London-based dealer who has been buying and selling vintage and antique musical instruments since the 1960s. “This was a huge amount for a nondescript object. It was just a piano, and it wasn’t even made for him.”

Unlike many other lots in the Sotheby’s sale, such as the snake bangle worn by Mercury in the “Bohemian Rhapsody” video that sold for around 100 times the £7,000 low estimate after fees, there was nothing about the baby grand that visually connected it with Queen’s lead singer-songwriter. Similar new Yamaha pianos currently retail at around £17,000.

Mercury’s Yamaha piano was offered without reserve at the 11th hour after an over-estimation

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby’s

“It’s always difficult to guess the value of so-called ‘association pieces’,” says Bingham, referring to musical instruments prized for being owned by a prominent individual. “In the past, I’ve always advised that they be offered at auction. The value is what two people are prepared to pay at the sale. It’s the only way that you can arrive at it.”

By selling Mercury’s piano without reserve, Sotheby’s ensured the positive optics of plenty of bidding and some kind of face-saving price, rather than a mood-flattening failure. After the auction, Sotheby’s said the price was “a record for a composer’s piano”.

However, despite the house’s self-congratulations, it is worth noting that Mercury’s Yamaha only achieved this record courtesy of Sotheby’s auction fees, which, in addition to a buyer’s premium of 20% on the £1.4m hammer price, include an extra 1% “overhead premium”. Back in 2000, in a sale staged by the auctioneer Fleetwood Owen, the upright Steinway model on which John Lennon composed “Imagine” was sold for £1.45m, or £50,000 higher than the hammer price for Mercury’s baby grand. (The buyer was none other than George Michael.)

But Lennon’s Steinway came with a lower buyer’s premium, resulting in an overall price of £1.67m (with fees), according to the Independent, around £70,000 lower than the premium-inclusive £1.74m paid for Mercury’s Yamaha. Of course, if inflation were taken into consideration, the £1.67m achieved for Lennon’s piano 23 years ago represents a far higher price.

That baby grand was not the only lot Sotheby’s finessed to turn the Mercury evening auction into another 100% sold event. One piece did in fact fail to sell: lot eight, a gruesomely sentimental genre painting of a Venetian beauty holding a rose, by the 19th-century Italian artist Eugen von Blaas, carrying a low estimate of £70,000. The work did not attract a single bid, yet the audience still gave it a round of applause.

Unfazed by this failure, Sotheby’s simply offered the von Blaas again at the end of the auction, having had four hours to resuscitate interest. The second time around, the painting sold to an Asian bidder at the back of the room for £69,850 (with fees), again below the low estimate.

Moments later, an ever-insouciant Barker was able to announce that Sotheby’s had triumphantly achieved a “white glove” sale, and euphoric staff members thumped out the opening drum beat of Queen’s “We Will Rock You”.

Of course, there is nothing illegal or unethical about an auction house dropping a reserve or offering a lot again to maximise returns for the seller and for the house. As Mercury, who was a regular bidder at Sotheby’s, put it in one of his most famous songs, it’s “A Kind of Magic”. And don’t magicians often perform their most audience-baffling tricks wearing a pair of white gloves?