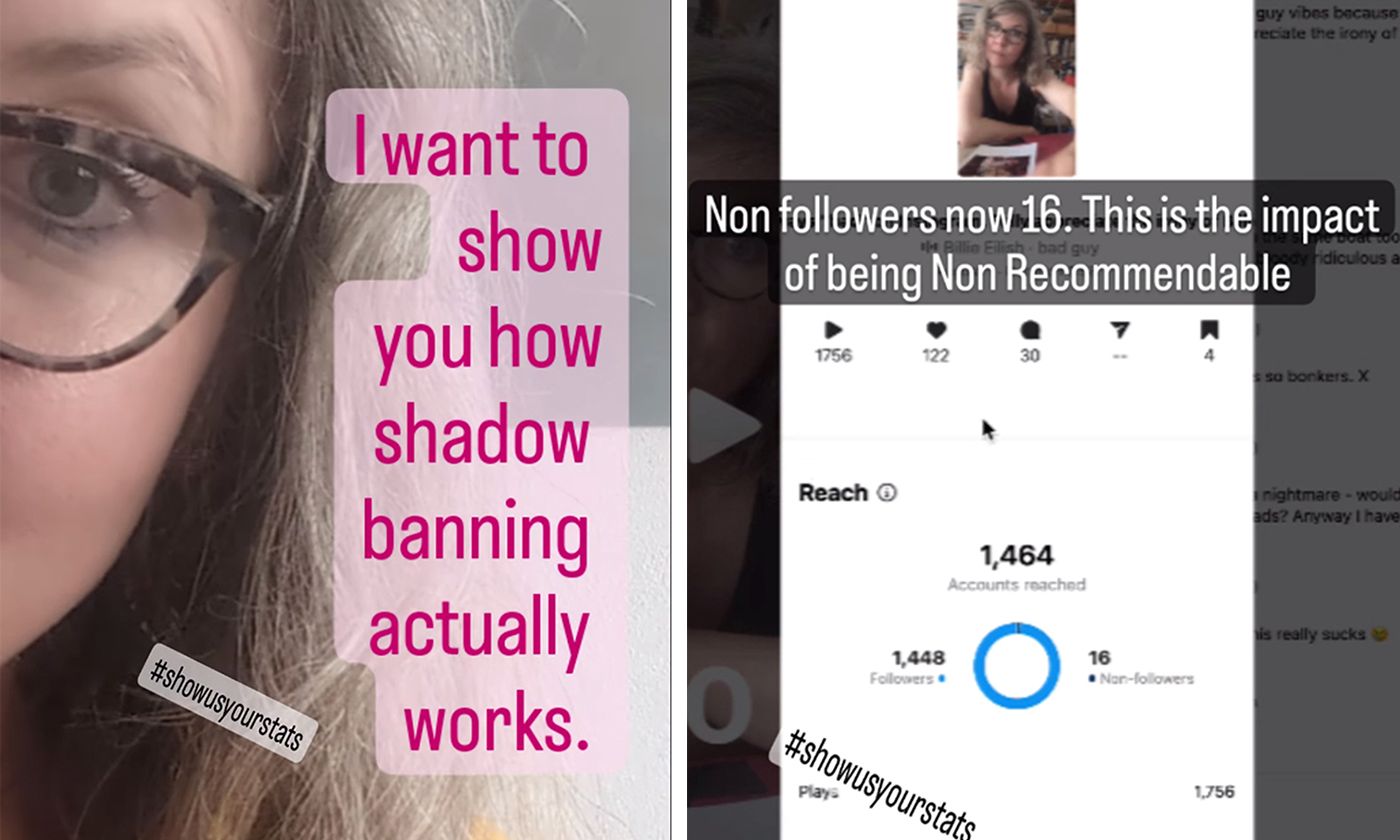

The artist Jessa Fairbrother has advocated for artists against shadow banning (left) and has used Instagram's professional settings to show how being "non-recommendable" has limited her account's visibility to non-followers Courtesy of Jess Fairbrother

Numbers don’t lie, and the art world is no exception. From Guerrilla Girls’ posters to the Burns-Halperin report, hard data has been employed to bypass equivocations, strip the veneer of virtue signalling, and deliver a reality check to artists and institutions alike. And so, when artists were recently handed numbers and insights into how their artwork is treated on Instagram, one of today’s most critical tools for creative and market visibility, the result should have been empowering. Instead, artists who had long suffered under Instagram's infamous “shadowban”—where a user's visibility on the platform was reduced by stealth—have been able since June to view their own suppression in quantifiable clarity. They were also reminded that, with the introduction of new, scantily defined, violation categories—including "Monetisation" and "Features You Can't Use"— they will need to continue to advocate for their community to have unrestricted access to the power of social media.

Summer’s end marked the long-anticipated enforcement of Europe’s Digital Services Act (DSA), which demands transparency from notoriously opaque platforms like Meta, owners of Instagram and Facebook. As the first major legislation to tackle online visibility, the DSA specifically calls out shadowbanning, and requires companies operating in Europe to notify, explain, and quantify content moderation actions to individual users. Despite a history of obscuring such practices, Meta has seemed to embrace the DSA and devoted themselves to preparing for its implementation. Nick Clegg, Meta's global affairs president, recently blogged: “The hard work of creating these pioneering new rules has come to an end, and the process of implementing them has begun.” In response to the DSA and other impending international regulations, Meta has indeed recently initiated transparency measures that give users around the world insight into the policies that have frustrated them most. Foremost among these transparency measures are the platform's recommendation guidelines.

The recommendation guidelines essentially bring shadowbanning to light, revealing how content can comply with community guidelines and yet still limit an account's ability to reach non-followers. Instagram's technology identifies content that "may go against" community guidelines and lists violations in a new section of a user's account status: “recommendation guidelines.” Users are given options to remove posts, edit offending text or appeal. When appeals fail, many artists opt to delete posts in the hope of freeing their accounts from suppression, only to enter a kind of violation loop—in which further content is flagged as soon as the existing "in violation" material is removed, because users are shown only a few violations at a time, without knowing the full extent to which past posts violate the guidelines. The resulting pressure to self-censor by deleting artwork that does not violate community guidelines raises questions over whether this is truly transparency on a previously existing policy, or a new way to target more content for suppression.

Many have either capitulated to this pressure or simply decided to ignore it. Others, though, are documenting the consequences of their account suppression, and the evidence paints a picture of enormous implications for artists who rely on a growing audience. Spencer Tunick, a prominent artist who organises large-scale nude photo shoots all over the world, spent months in a violation loop. He was finally freed after deleting artwork and limiting posts to benign non-art content, and within a week he had gained an astounding 90,000 new followers. He has an upcoming exhibition but worries that promoting it will only land him back in trouble.

Screen grabs from Spencer Tunick's verified Instagram account @spencertunick, from just before his account was suppressed, with 204k followers (left), and after he was freed from months in a violation loop, with 294k followers (right) directly after being recommendable again (2023) Courtesy of Spencer Tunick

To track and share their evidence of account suppression, some artists are using “insights,” a tool available to professional accounts on Meta, which shows engagement and reach for individual posts. Jessa Fairbrother, who has also experienced the violation loop, believes artists ought to be taking suppression more seriously. With Instagram reels, she illustrates the effects of her suppression, showing posts that reached hundreds versus those that reached only handfuls of non-followers, and describing the implications for her professional practice. Her aim is to educate those who may not understand what is happening to them. “This isn’t an individualised problem about me not being able to share [my] art—this is fundamentally about who has access to tools shaping the culture,” Fairbrother tells The Art Newspaper, tools which “everyone is under the impression they can use in the same way. They can not.”

Screen grab from Jessa Fairbrother's 12 August Instagram reel to illustrate the effect of recommendation guidelines violations and how to use the "insights" tool on professional accounts Courtesy of Jessa Fairbrother

Since the introduction of recommendation guidelines violations, Meta has silently rolled out more violation categories in Account Status, including “Monetisation,” “Features You Can’t Use,” and “Your Content Reach". This last category appears to be active only in Europe, and relates to content that is not recommendable to existing followers. The accompanying hyperlinked guidelines are, thus far, scant and vague.

For years, artist and activists gathered proof of the existence of the shadowban by monitoring their own accounts and accumulating experiences. This labour was ultimately influential in not just uncovering it, but in the very regulations that now demand transparency. As platforms like Meta adapt, and more data becomes available, our vigilance is still required to advocate for ourselves and our community. Noting the impactful history of data collection in the art world, Fairbrother comments, “maybe every good action starts with a spreadsheet".