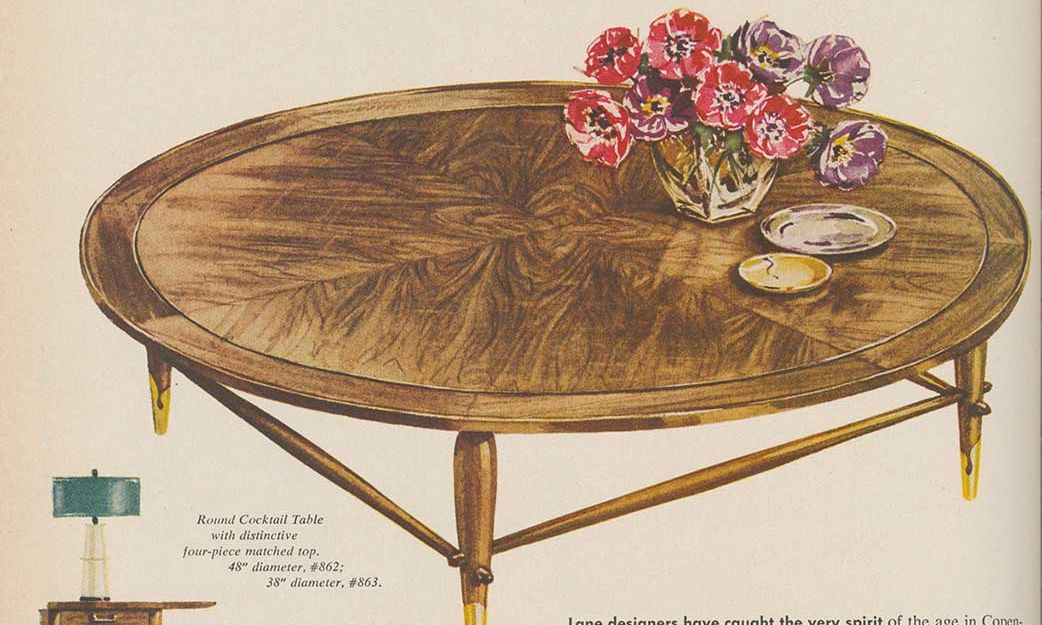

“The concept of Danish design was consciously invented with a clear marketing narrative”: an advert for American company Lane’s Copenhagen series of furniture in Life magazine, 1958

Courtesy University of Chicago Press

This very succinct and engaging book, on how Danish design and Danish Modern helped shape 1950s American design culture and taste, weaves its story around the history of two chairs designed in 1949, their origins, methods of making and place within the Danish and, especially, American markets: Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair and Hans Wegner’s the Chair (originally called the Round Chair).

Among the most recognisable of Danish chairs, they are described by Maggie Taft as “emissaries” for the strategic creation of an American export market for a wider range of Danish furniture and domestic objects. So successful was this strategy that, gradually, not only was Danish production shaped for American consumers but, in the US itself, Danish Modern became a term applied to American-made furniture and product design.

From 2006 onwards in publications in both Danish and English, including his 500-page book Danish Modern Furniture, 1930-2016: The Rise, Decline and Re-Emergence of a Cultural Market Category, the economic historian Per Hansen proposed that the concept of Danish design was consciously invented with a clear marketing narrative, underpinned by the idea that it was “democratic, social and honest, created out of a unique sense of moderation and regard for surroundings and human need”. The creators and drivers of this narrative were a coordinated network of Danish designers, makers, their organisations and the Danish government.

Hansen’s research—a major contribution to design history without which the title under review is unimaginable—was revelatory. He explained that what began as a plan to revive and diversify the Danish economy in the 1930s by exporting to European markets, was only realised from the late 1940s when it focused on the American market. In Danish Modern Furniture, 1930-2016, Hansen devoted a whole chapter to the American story. While perhaps Taft could have more fulsomely

acknowledged Hansen’s work (there are some footnotes), she delves deeper into the key role played by the American market in creating and transforming the idea of Danish design, consumer responses and copies.

Taft begins her book with the origin stories of her two protagonist chairs, placing them within the Copenhagen context where, at the top end of the market, “craftsmanship was king”. It was members of the Cabinetmakers Guild and certain architects (rather than the wider Danish furniture trade) that championed this idea; along with the export-minded Danish government, the department store Den Permanente and various trade bodies, they led the push into the US.

With the help of the post-war Marshall Plan, the Danish government was instrumental in moving away from import tariffs on woods, especially Thai teak, in favour of subsidies for Danish cabinetmakers, who were limited by an insufficient supply of native timbers. Taft highlights the backstory of the commercial relationship between Denmark and Thailand, which began in 1858. As a result of the Danish subsidies, between 1952 and 1957 teak became the wood most used in and associated with Danish furniture exported to the US.

Taft deftly organises her chapters into a compelling narrative that explains, in chapter two (“Made in Denmark”), how Juhl’s and Wegner’s chairs were modified in design and manufacturing technique for export, and then (in the case of Juhl’s chair as well as other furniture designs) for manufacture in the US. Between 1949 and 1960, the majority of Danish factories had under ten employees—too few to meet the needs of the US market, which consumed at least 50% of the entire production of the new Danish Modern furniture.

Chapter three (“At Home with Danish Design”) explores the sellers, tastemakers and consumers who promoted Danish design, including in exhibitions. Especially fascinating are the motivations of American consumers revealed in correspondence with Den Permanente. More traditional tastemakers included Edgar Kaufmann Jr, of the Museum of Modern Art in New York; he was an influential champion of Juhl and saw meaningful parallels between Danish and American design cultures. “Both are drawn to organic design … [which] blends form, structure and utility into a vivid whole,” he wrote. Parallel connections were observed by American design writers, notably the Cold War warrior Elizabeth Gordon, the editor of House Beautiful and a keen admirer of Danish Modern. For Gordon, both cultures exemplified democracy and thus Danish design was spuriously enlisted into the McCarthy-era fight against Communism within the sphere of the American home.

The final chapter in the book (“Mail Order Danish Modern”) covers the plagiarising of Danish Modern furniture, with Wegner’s the Chair described at the time as “the most stolen-from design in the world”. Taft argues that the proliferation of copies helped grow the concept of a Danish Modern style and was instrumental in popularising it. Ironically, by 1968, when the US Federal Trade Commission banned the “misleading” use of the word Danish for furniture produced outside of Denmark (except for “Danish manner” or “Danish style”), copies had ultimately destroyed the export market for such furniture. These and other stories in Taft’s book make it essential for an understanding of post-war Danish and American design.

• Maggie Taft, The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America, University of Chicago Press, 184pp, 16 colour & 36 b/w illustrations, $22.50/£18 (hb), published 22 May

• Christopher Wilk is the keeper of performance, furniture, textiles and fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London