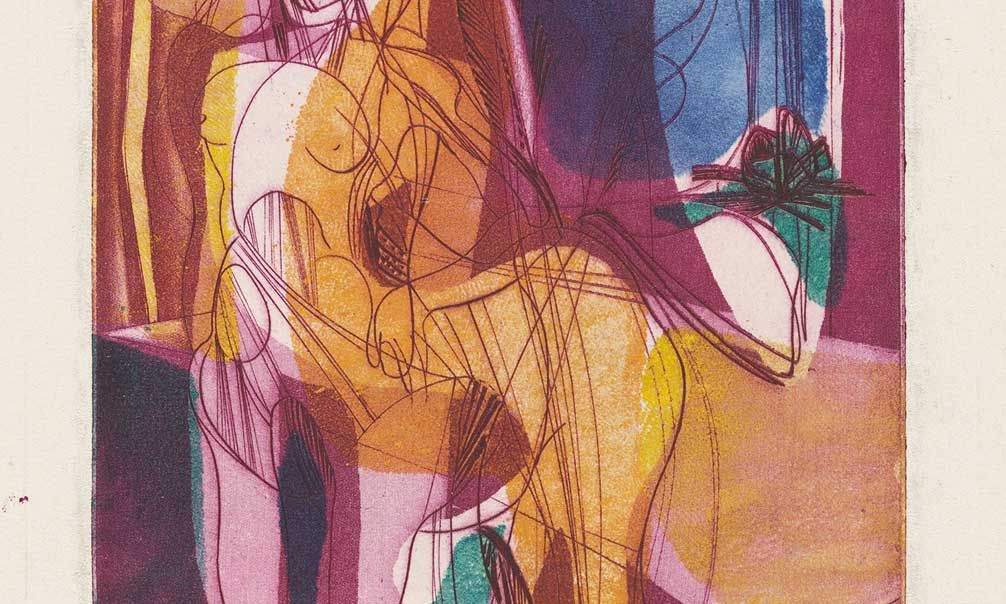

Stanley William Hayter’s Centauresse (1944). In 1940 Hayter relocated Atelier 17 from Paris to New York

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

It is no secret that Surrealism influenced the development of Abstract Expressionism. Martica Sawin’s rich study, Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School (MIT Press 1995), charted in great detail the significant cultural exchange that occurred between 1938 and 1947, when Parisian artists fleeing Nazi Europe made their home in Manhattan.

However, what has so far been largely overlooked by art history—Sawin’s account included—is the mechanism by which this exchange took place. Surrealism was well known in New York before the Second World War, but it was not until its artists were living there that American art saw a radical shift. Where was it, then, that Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and the rest saw Surrealism in action? The surprising answer, writes the author and art critic Charles Darwent, is a small, grubby workshop run by an English printer.

This book’s title is perhaps a little misleading, for while over an introduction and eight chapters, Darwent provides an overview of the cultural overlap between Surrealism’s heavy hitters and America’s burgeoning AbExers, it is, in essence, a portrait of one man, Stanley William Hayter (1901-88), and his influential print studio, Atelier 17. Founded in Paris in 1927, Hayter’s workshop was central to the Parisian avant-garde and critical to the revival of burin engraving as a creative medium. Relocated to New York in 1940, it found a home at the New School, becoming a crucible for young American artists who rubbed shoulders with major European figures such as Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró and André Masson. As Darwent writes: “It would be easier to list the avant-garde sculptors and painters who did not pass through the atelier’s doors between 1927 and 1947 than those, from Picasso to Pollock, who did.”

While it is true that Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell and other seminal American artists worked at Atelier 17 in the 1940s, the extent of its influence on their paintings is open to conjecture. The tantalising problem is that Hayter, despite being a master printer, did not keep proofs and no archive of his studio’s production exists. Rothko’s time at the studio is evidenced by a single extant etching. Motherwell only produced a handful of prints there before giving up printmaking for 20 years. And not one of De Kooning’s prints has survived. Furthermore, the self-deprecating Hayter was unwilling to take credit for his role in the formation of any artist. Nevertheless, Pollock named him as one of his two masters, the other being the Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton.

Pollock’s six-month stint at Atelier 17 is the subject of a whole chapter (“Pollock Makes A Print”), which provides an enlightening account of how the artist’s experiments with a tin of paint suspended from Hayter’s ceiling, coupled with his night-time explorations of movement and line in intaglio, directly shaped his mature style. Thus, it was in a small room on the seventh floor of the New School at 66 West 12th Street that Pollock learned from Hayter, Darwent observes, “less a way of painting than a philosophy, a means of freeing the mind through repeated, cyclic motion…a way of working that looked accidental while being wholly controlled”. The art critic Clement Greenberg saw Pollock’s new style as uniquely American and, intriguingly, made the emphatic claim two decades later that the artist had learned nothing from Hayter, despite the obvious parallels between the two men’s work. As Darwent asks pointedly: “Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?”

Hayter helped to make plates for Louise Bourgeois’s 1947 illustrated book, He Disappeared into Complete Silence

© The Easton Foundation/DACS, London, 2023

Although a significant proportion of the students at Atelier 17 were women, Darwent’s account is weighted firmly towards their male counterparts: in fairness, he recommends that Christina Weyl’s outstanding study, The Women of Atelier 17 (Yale 2019), be read in conjunction with his own. One woman who does come under his spotlight is Louise Bourgeois who, despite not being a Surrealist, was heavily influenced by their ideas. Living in New York since 1938, she first visited Atelier 17 after the war, when the studio had moved to East 8th Street. She evidently had an extreme dislike for Hayter. In 1947 he had helped her make nine plates for her illustrated book, He Disappeared into Complete Silence, which to her frustration sold just a handful of copies—a failure she inexplicably blamed on Hayter and for which she never forgave him. A half-century later, she contemptuously referenced his name in the titles of several works, a move that ironically served to help preserve his memory.

It is fair to say that few modern British artists have been as influential internationally as Stanley William Hayter. Yet, although well known among printmakers, he and his studio were for many years quietly written out of art history. His importance, Darwent argues, was not primarily in his expertise as a printmaker, but in facilitating a unique space where experiment and a very particular kind of creative freedom were encouraged. In focusing on the artist’s activities in New York, this admirably lucid and carefully researched book makes a compelling case for Hayter’s role in the revolution that took place in American painting during the 1940s. It is also a stark reminder that art history remains a work in progress.

• Charles Darwent, Surrealists in New York: Atelier 17 and the Birth of Abstract Expressionism, Thames & Hudson, 256pp, 80 colour illustrations, £25 (hb), published 16 March 2023

• David Trigg is an independent writer, critic and art historian, and a regular contributor to Studio International and Art Quarterly