We bring news that matters to your inbox, to help you stay informed and entertained.

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy Agreement

WELCOME TO THE FAMILY! Please check your email for confirmation from us.

“TheG.I. Bill Restoration Act is probably the only shot we have of some kind of race-specific reparations in this country,” said Richard Brookshire, co-founder and CEO of the Black Veterans Project.

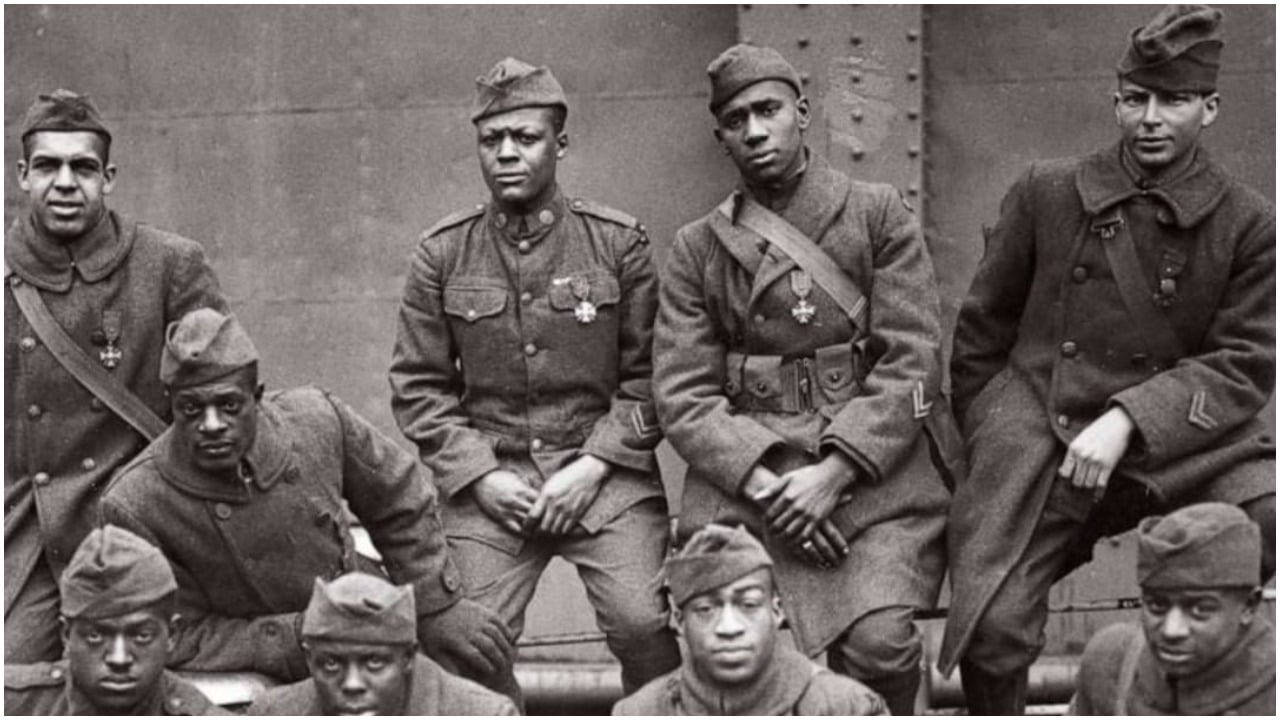

Black World War II veterans and their descendants have yet to receive their overdue G.I. Bill benefits; however, some House Democrats hope to change that.

On Feb. 28, House Reps. James Clyburn (D-SC) and Seth Moulton (D-MA) re-introduced the Sgt. Issac Woodard, Jr. and Sgt. Joseph H. Maddox G.I. Bill Restoration Act in an effort to seek justice for veterans and their descendants who are owed numerous benefits.

Richard Brookshire, co-founder and CEO of the Black Veterans Project, told theGrio that the G.I. bill might have to overcome some challenges before being signed into law.

“I honestly feel like the G.I. Bill Restoration Act is fantastic, but I also know the political feasibility of that is very slim,” he stated.

He continued, “In most respects because of the cost and then because there seems to be some level of disagreement about whether or not passing a piece of targeted racial policy like that would withstand judicial review.”

In 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill into law to assist qualifying veterans and their family members with paying for higher education, training programs and other benefits, according to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. Yet, many Black veterans did not receive any benefits after putting their life on the line for the United States.

Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA), who recently spoke with theGrio, called it a “disgrace.”

“These Black veterans who served their country, who died, whose families are still trying to recoup and they can’t even get the benefits from what they deserved only because they were Black….it’s a shame and disgrace,” said Lee, who is running for U.S. Senate in California in the 2024 election.

This latest measure was named after veterans Woodard and Maddox to honor the two Black sergeants who faced discrimination in the U.S. after serving in World War II.

On Feb. 12, 1946, just hours after being honorably discharged from the United States Army, a South Carolina police officer violently assaulted 26-year-old Woodward and left him permanently blind. President Harry Truman was so horrified by the ordeal that on June 26, 1948, he issued an executive order to desegregate the armed forces, TIME Magazine reported.

According to a press release from Clyburn’s office, Maddox was medically discharged from the army after sustaining an injury. Upon his return to the U.S., he was accepted into Harvard University. However, he was denied tuition assistance. The NAACP and Veteran Affairs advocated on Maddox’s behalf to ensure justice was served.

Clyburn’s office further highlighted the racial disparities that occurred after Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill into law.

“In 1947, only 2 of more than 3,200 home loans administered by the VA in Mississippi cities went to Black borrowers,” read his statement. “Roughly 19% of white World War II veterans earned a college degree…compared to just 6% percent of Black veterans.”

It continued: “Black veterans sacrificed for this country because they believed in its promise of justice and equality for all. Yet, while the original G.I. Bill led to decades of prosperity for post-World War II America, this prosperity was not extended to the Black service members.”

Brookshire told theGrio that other discriminatory practices, such as redlining, also contributed to widening the racial wealth gap between Black and white veterans.

“You have a system in an apparatus in this country that was rolling out a social welfare program that helped to build and bolster the white middle class for the first time in history and Black folks were largely locked out of it,” he said.

He continued, “It mostly played out through redlining because the utilization of the VA home loan was at the state level. So, it wasn’t given out at the federal level, which would have been able to help circumnavigate some of the challenges.”

For the G.I. Bill Restoration Act to move forward, it must first be passed in the House and then the Senate before it lands in the Oval Office for President Joe Biden to sign into law.

Brookshire told theGrio, “The G.I. Bill is probably the only shot we have of some kind of race-specific reparations in this country and I think it should pass in full.”

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!