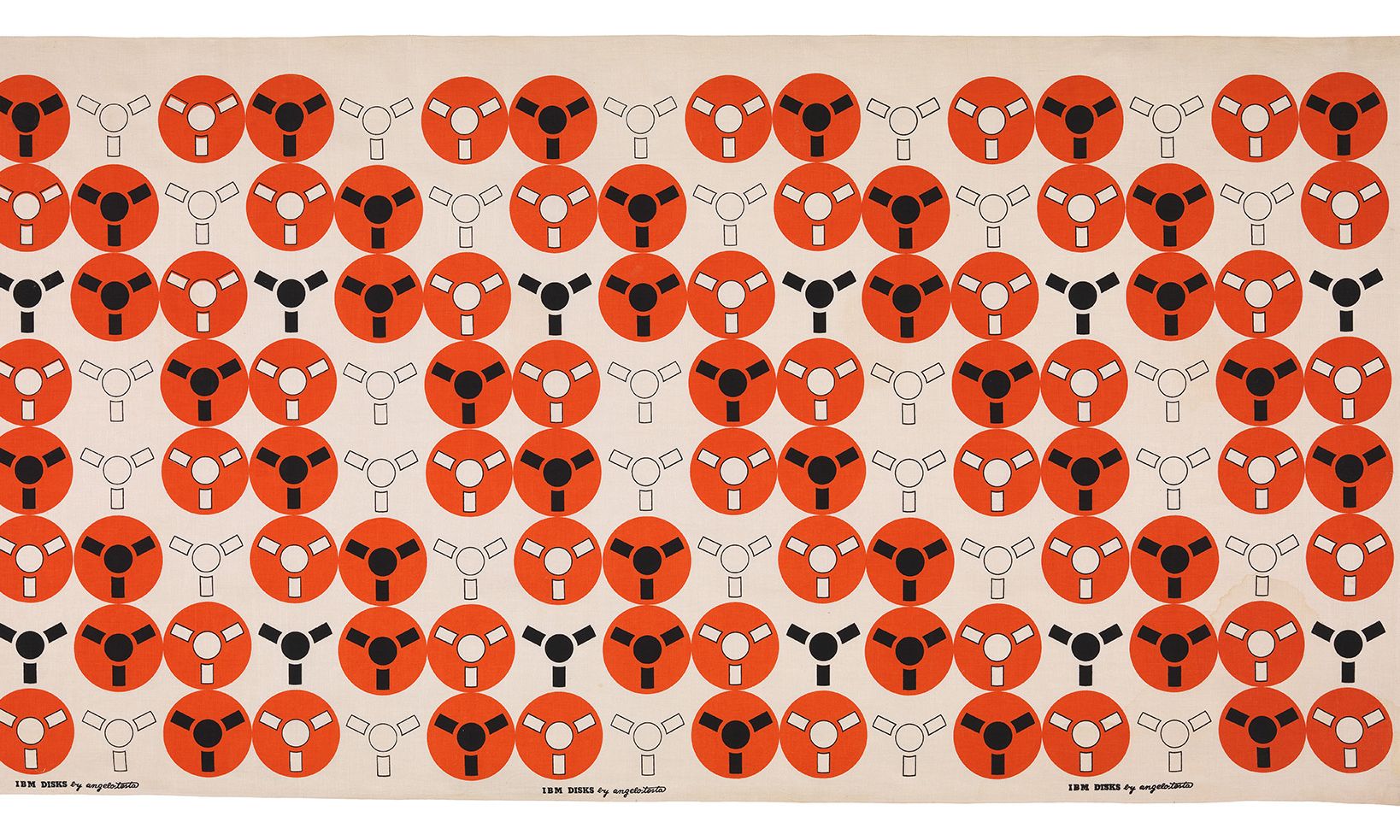

Angelo Testa’s IBM Disks (1952–56), screenprinted on linen; in 1956 the fabric designer also translated Paul Rand’s IBM logotype onto fabric © Museum Associates/LACMA

As the parallel worlds of artificial intelligence and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) continue to dominate art-world discourse in 2023, it is tempting to conceive of the relationship between art and technology as a project of futurity alone, defined by the kind of rampant obsolescence we associate with market trends and media cycles. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s (Lacma) exhibition, Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982, upends that presumption as it examines the rise of creative production in the age of the mainframe, drawing urgent throughlines between emergent coding systems and digital art as we understand it today.

In his 1986 essay Visual Intelligence, the art historian Frank Dietrich discussed the way scientific breakthroughs influenced artistic practice during the first 20 years of the computer art movement. “For the first time,” he wrote, “computers became involved in an activity that had been the exclusive domain of humans: the act of creation.” Coded explores the interdisciplinary underpinnings inherent to the act of creation, highlighting the artists, writers, musicians, choreographers and filmmakers producing the nascent algorithmic models we live with today.

The exhibition’s ambitious scope includes more than 100 objects made by 75 artists from all over the world, a number of whom are being shown at Lacma for the first time. The show’s chronological point of origin is 1952, the year the first entirely aesthetic image was rendered by computer, and ends in 1982, when the personal computer usurped the mainframe as the technological power du jour.

The Friendly Grey Computer—Star Gauge Model #54 (1965) by Edward Kienholz © Estate of Nancy Reddin Kienholz, courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, California, digital image © 2023 The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

The exhibition is organised into six major sections that trace computer art’s history, including work by pioneers like Edward Kienholz, whose anthropomorphic 1960s machines anticipated the rise of personal computing, and Vera Molnár, whose plotter drawings linked the industrial rise of robots with the regimented paintings of Paul Klee. Other highlights on view are renderings by Frederick Hammersley using Art1, one of the earliest computer programs designed specifically for artists, and an animated poem code written by Stan VanDerBeek, an artist who believed that computers could lead to “new ways of communicating that involve the artist in a larger matrix of machines and other people”.

Computer-generated or analogue, the works on display in the exhibition cohere into a narrative of undeniable interconnectivity, organically gleaning from movements like Op art and Conceptual art to imbue their proto-virtual endeavours with meaning. The show “brings to light early digital or computer art that has long been overlooked, recontextualising it to encourage a new way of looking at mainstream art of the period”, says Leslie Jones, Lacma’s curator of prints and drawings. “There are interesting parallels between computer art and contemporaneous mainstream movements like Minimal, Conceptual and Op art, notably in their mutual embrace of systematic and algorithmic approaches to art making.”

Coded also coincides with a presentation facilitated by Lacma’s Art + Technology Lab. This two-part interactive experience will function both as an homage and response to Victor Vasarely’s unrealised proposal for the museum in 1971. The Conceptual software artist Casey Reas’s METAVASARELY will be available online concurrent with the display of a new work of his at Lacma (9 April-2 July).

• Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, until 2 July