We bring news that matters to your inbox, to help you stay informed and entertained.

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy Agreement

WELCOME TO THE FAMILY! Please check your email for confirmation from us.

A funeral service for Nichols, who died after being beaten by Memphis police officers during a traffic stop, is scheduled to be held on Wednesday.

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (AP) — Tyre Nichols ’ mother was just steps away from her son but couldn’t hear his anguished cries.

Beaten and broken, struggling to survive, Nichols had called out for her as five Memphis Police Department officers punched him, kicked him, and hit him with a baton after a traffic stop on Jan. 7.

Nichols, 29, who lived with his mom and stepdad, had slipped from the grasp of police after he was pulled over, dragged from his car and hit with a stun gun. Caught minutes later near their home and beaten savagely by five officers, he screamed, “Mom! Mom!”

Moments later, the police knocked on the mother’s door, but not to alert RowVaughn Wells that her child had been savagely beaten, according to Rodney Wells, her husband and Nichols’ stepfather. They said Nichols had been arrested for driving under the influence and was being taken to the hospital. Police said they could not go to the hospital because their son was under arrest.

So they waited.

Memphis Police Director Cereyln “CJ” Davis, a mother herself, didn’t find out what her officers had done to Nichols until later either. The lack of police supervisors on the scene would be noted by many after Nichols died Jan. 10.

The fact that no one felt compelled to fill her in until the following day raised questions about the culture of her department she would have to answer in the coming days, even as she was asking them herself.

“There were failures of who should render aid, who should have notified, who went to the mother’s house, how they communicated,” Davis told the Associated Press in a Jan, 27 interview. “Why did the chief get notified at 4 o’ clock in the morning and the incident occurred at 8 o’ clock the previous night?”

It was around that same time of 4 a.m. that RowVaughn Wells received a call from a doctor at the hospital where he had been taken, Rodney Wells said. The doctor told them to get to the hospital immediately.

When she got there, she found Nichols on life support. While Wells was seeing her son’s battered body for the first time, Davis’ police department was swinging into damage control.

The coming hours and days in Memphis would set the tone for America’s latest reckoning over police brutality, with RowVaughn Wells and Cerelyn Davis on opposite sides of the same tragedy. Their lives would be altered, in dramatically different ways.

Wells and her family seethed, cried and mourned for Tyre Nichols, the happy-go-lucky skateboarder and amateur photographer who came to Memphis from California about a year ago. She ultimately hung on to the hope her son’s fate might mean something, taking its place as it did in the long line of young Black men who have died at the hands of police.

Davis, the first Black woman to run the Memphis Police Department, faced heavy criticism. As she and other city officials came to grips with what had happened, they gradually took steps to hold the officers accountable, share the horror of the case with the public, and try to minimize the possibility that the incident could set off unrest in Memphis and beyond.

But she would be called out in vivid terms at Nichols’ funeral as a beneficiary of the progress that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was in Memphis to fight for when he was shot to death more than half a century earlier.

At 6:03 a.m. on Jan. 8, the police department posted a vague statement on social media saying that Nichols had two “confrontations” with police. He had “complained of having a shortness of breath, at which time an ambulance was called to the scene,” the statement said.

Wells knew better by then. She had seen him bruised, swollen, hooked up to machines.

Memphis’ fire department later revealed that 27 minutes elapsed from the time emergency medics arrived on the scene to the moment when an ambulance took him to a hospital.

“When I walked into that hospital room, my son was already dead,” Wells said during a Jan. 23 news conference.

Doubts about the police department’s initial account only grew. A photo of a bruised Tyre in the hospital was distributed in the media. Activists questioned the department’s account and pushed for release of the arrest video.

Nichols’ family hired lawyer Ben Crump, known for representing the families of others struck down by police, including George Floyd. Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police in 2020 led to nationwide protests and raised the volume on calls for police reform.

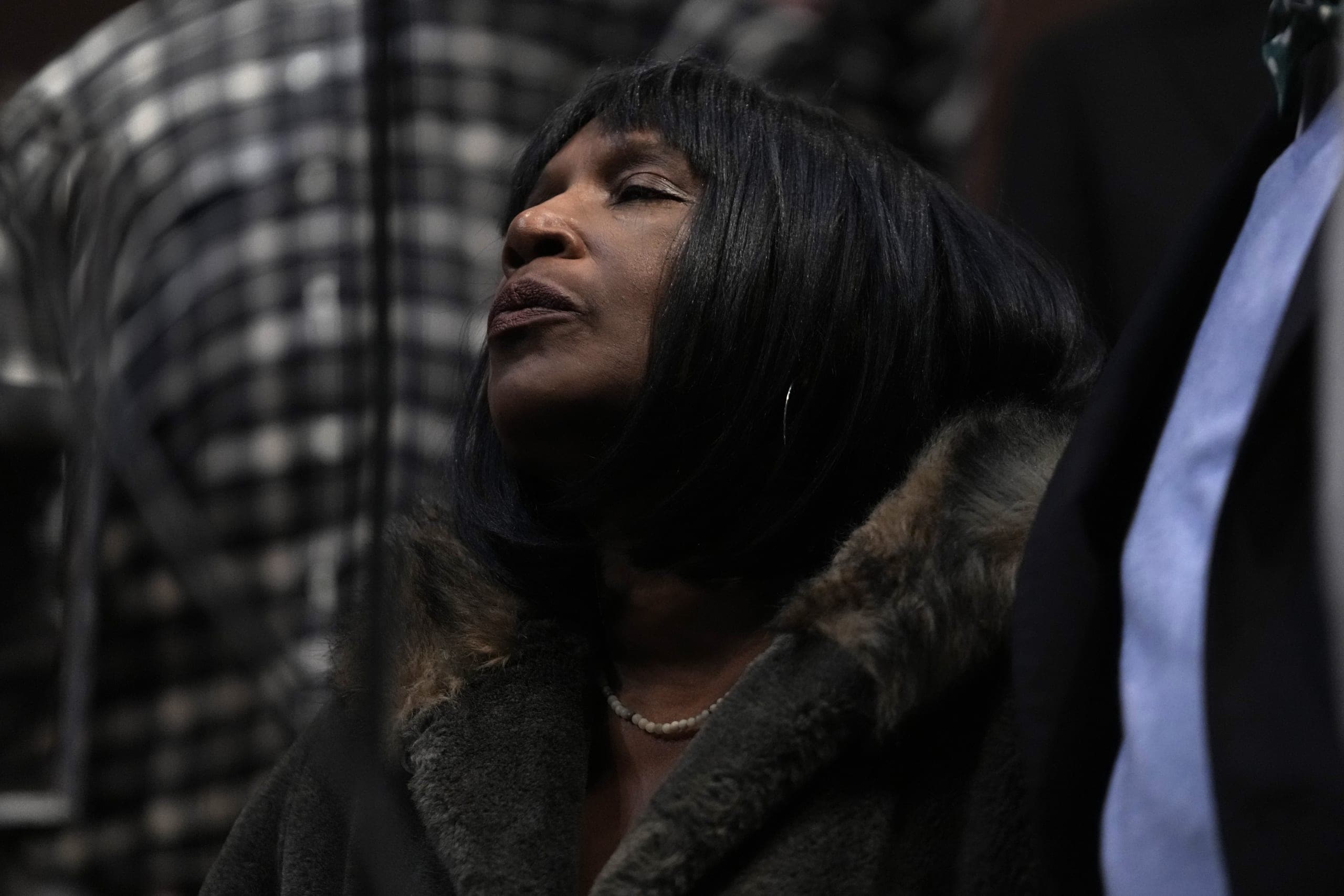

Wells cried throughout a Jan. 17 memorial service for her son but would not speak publicly until later.

Gradually, a fuller portrait of Nichols emerged. He had lived with his mom and stepfather and made boxes at FedEx alongside Rodney Wells. He had two brothers, a sister and a 4-year-old son. He was an amateur photographer who loved sunsets and skateboarding.

Tyre had his mother’s name tattooed on his arm.

“This man walked into a room, and everyone loved him,” said Angelina Paxton, a friend who traveled from California for the service.

That same day, Memphis officials pledged to release video of the attack.

The five officers were fired Jan. 20 after an internal police investigation revealed violations of police rules, including excessive use of force, and failure to intervene and render aid.

In a statement, Davis called their actions “egregious.”

The family met with authorities to see the video — horrific footage RowVaughn Wells said she was unable to watch at that meeting. Later, she warned parents to avoid showing it to their children.

Wells said she was inside her house at the time of the beating, waiting for Tyre to get home and give his customary cheerful greeting of “Hello parents!”

“For a mother to know that their child was calling them in their need, and I wasn’t there for him, do you know how I feel right now?” Wells told media during a Jan. 27 news conference.

“I wasn’t there for my son. I was telling someone that I had this really bad pain in my stomach earlier, not knowing what had happened,” she said. “But once I found out what happened, that was my son’s pain I was feeling.”

She also shared how an ordinary day had turned horrible.

Tyre, on the day of the arrest, had seen her pulling out some chicken before he left the house at around 3 p.m. to snap pictures of the sunset at a suburban park, she said.

“He said, ‘Mom, are you cooking chicken tonight?” I said “Yes.”

“He said, ”How are you cooking it?”

With sesame seeds.

“He loved that.”

In a late-night video statement released Jan. 25, Davis said she had met with the Nichols family and offered her condolences. She promised to continue investigating other officers’ actions.

“I am a mother, I am a caring human being, who wants the best for all of us,” Davis said. “This is not just a professional failing. This is a failing of basic humanity.”

Officers Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills Jr. and Justin Smith were charged the next day — 19 days after Nichols’ arrest. It’s a length of time that Crump said should be a “blueprint” for other police agencies to follow when dealing with similar situations.

When asked about the charges, Rodney Wells told the AP that the family was “fine with it.”

He also said his wife thought Davis was doing an “excellent” job.

Friday, Jan, 27 was the day Memphis and the nation had waited for — the video release.

Hours before it was posted by the city, Davis told the AP that the footage failed to show what still remains a mystery — why Nichols was stopped in the first place.

Officers were “already amped up, at about a 10,” she said, when the video started. The members of the crime-suppression team known as the Scorpion unit were “aggressive, loud, using profane language and probably scared Mr. Nichols from the very beginning,”

“We don’t know what happened,” Davis said. “All we know is the amount of force that was applied in this situation was over the top.”

Rodney Wells, Davis and community leaders had called for protests to be peaceful, in honor of King’s belief in nonviolent action.

Protesters blocked an interstate bridge, but there was no violence. No property damage. No arrests.

Davis disbanded the Scorpion unit on Jan. 28, after “listening intently” to the Nichols family, community leaders and other officers on the team.

Crump said the Nichols family considered the move “appropriate and proportional to the tragic death of Tyre Nichols.”

He also called it “a decent and just decision for all citizens of Memphis.”

Tyre Nichols was laid to rest on Feb. 1. The funeral at Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church, delayed by icy weather, featured a rousing choir, a eulogy by the Rev. Al Sharpton and a visit by Vice President Kamala Harris.

Also present were relatives of Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, Botham Jean, Jalen Randle and Floyd — Black people who also had been cut down by police.

Harris praised Nichols’ parents for their extraordinary strength, courage and grace throughout the ordeal.

In his eulogy, Sharpton said he had taken his daughter Ashley early that morning to the site of the former Lorraine Motel, a Black-owned business where King was shot on April 4, 1968. The motel is now the National Civil Rights Museum.

Sharpton noted the civil rights movement led by King opened doors for Black city workers in Memphis and elsewhere and said the five Black officers insulted King’s legacy by beating Tyre to death.

Sharpton called out the officers and Davis, reminding them of those who marched, went to jail and died while fighting for racial equality.

“You didn’t get on the police department by yourself. The police chief didn’t get there by herself,” he said.

Despite her grief, RowVaughn Wells spoke, too. Speaking from a lectern in the large church, she wiped away tears and said she believed her son “was sent here on an assignment from God.”

“And I guess now his assignment is done. He’s been taken home.”

Someone in the audience yelled that Nichols was going to change the world.

“Yes,” his mother said, nodding. “Yes.”

And then, once again, she praised Davis for acting swiftly.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!