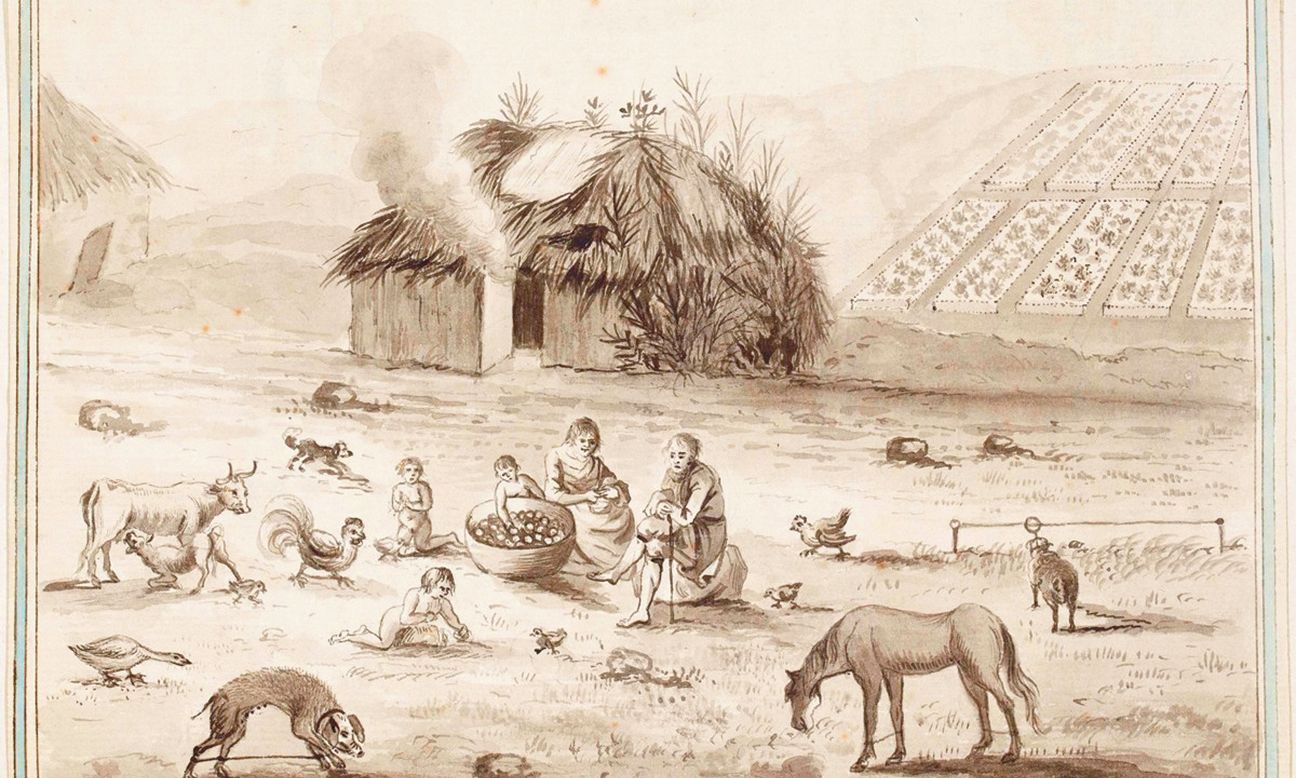

A pen-and ink-drawing from the 1770s of a tenant farming family and their “Irish Cabbin”, revealing the gulf between rich and poor in 18th-century Ireland Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

In 1776 Lady Louisa Conolly wrote to her sister Emily of the success of her new long gallery, in the palatial Castletown House in county Kildare, serving its intended purpose as the social centrepiece of her house party, with the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland as guest of honour: “Lord Harcourt was writing, some of us played at whist, others at billiards, Mrs Gardiner at the harpsichord, others at work, others at chess, others reading, and supper at one end… I have seldom seen twenty people so easily disposed of.”

House and Home in Georgian Ireland is an absorbing compendium of ten essays on design and life in the long 18th century. Covering themes such as The Merchant House in Eighteenth-Century Drogheda (by Aisling Durkan), Entertaining Royalty after the Union (by Judith Hill, featuring Lady Conolly) and ‘A Taste for Building’: Domestic Space in Elite Female Correspondence (by Priscilla Sonnier) perhaps inevitably, the volume devotes much space to the homes of the wealthy merchant and Anglo-Irish landlord classes, for which rich archival and material evidence survives in handsome urban terraces and sumptuous country mansions.

However, humbler lives do find a place. In the same year as Louisa’s party, Arthur Young (1741-1820), a farmer, writer and inveterately curious traveller, set out on the first of three years travelling around Ireland. A startling drawing, entitled the “Irish Cabbin”, from the extra illustrations in Young’s own copy of A Tour in Ireland with General Observations on the Present State of that Kingdom, the book he published in 1780, shows a building which could not be further from the whist players at Castletown if it had been built on the dark side of the Moon. It is illustrated in Claudia Kinmonth’s superb essay, Communality and Privacy in One or Two-Roomed Homes Before 1830, which, for me, is the star of this essay collection.

The “Irish Cabbin” is a windowless hovel with a decaying thatch, smoke pouring from the door. The family, including three stark-naked children, have understandably chosen to eat their large pot of boiled potatoes in the open air. By the standards of many small tenant farmers, this family was not poor: they have a cow and calf, a horse, a pig, sheep, geese, chickens and well-tended potato fields. But as reported by horrified English travellers who viewed deprivation as fecklessness—while at the same time being offered and accepting hospitality—they had almost no other possessions.

Even as the horrible John FitzGibbon, a lawyer and future lord chancellor and Earl of Clare cited in Tony Barnard’s essay Baubles for Boudoirs, was laughing at his footmen burning their fingers on his silver plates, Young’s “cabbin” family probably owned no cooking implements or tableware except for that potato pot. Kinmouth brilliantly disinters the barely recorded lives of the majority of the people of Ireland from lean scraps of material and literary evidence.

The book’s editor Conor Lucey, an associate professor of architectural history at University College Dublin, contributes the final essay, focused on another (much wealthier) group from the shadows: the single men, mostly professional but including some gentry, living in urban lodgings. There is certainly more work to be done on an even shadowier group, the “single Lady” mentioned in one advertisement he illustrates, which promises rooms in a “desirable neighbourhood” suitable for singletons “or a small family that would not require much room”.

Some of the essays are dryly academic but most shine flashes of light on individual lives: Dean Swift, the great literary satirist, owned the first recorded silver decanter labels, as well as six china coffee cups. As the century proceeded, the rich found new ways to show off their wealth and status. In 1755 the invaluable Mrs Mary Delaney, later famed for her exquisite cut-paper collages, wrote of “my ‘dining-room’, vulgarly so-called”, and Patricia McCarthy (in A Male Domain? The Dining Room Reconsidered) writes of the fortunes spent on imported glass, silver and china to furnish these newly fashionable spaces, which she sees as essentially male territory, the setting for ferociously heavy drinking once the ladies removed to the drawing room.

On occasion there were no ladies: in 1747 Lord Chancellor Robert Jocelyn gave a dinner in Dublin for 12 Peers, which apparently included a fricassée of frogs and a badger flambé—alas, there is no illustration, not even a recipe.