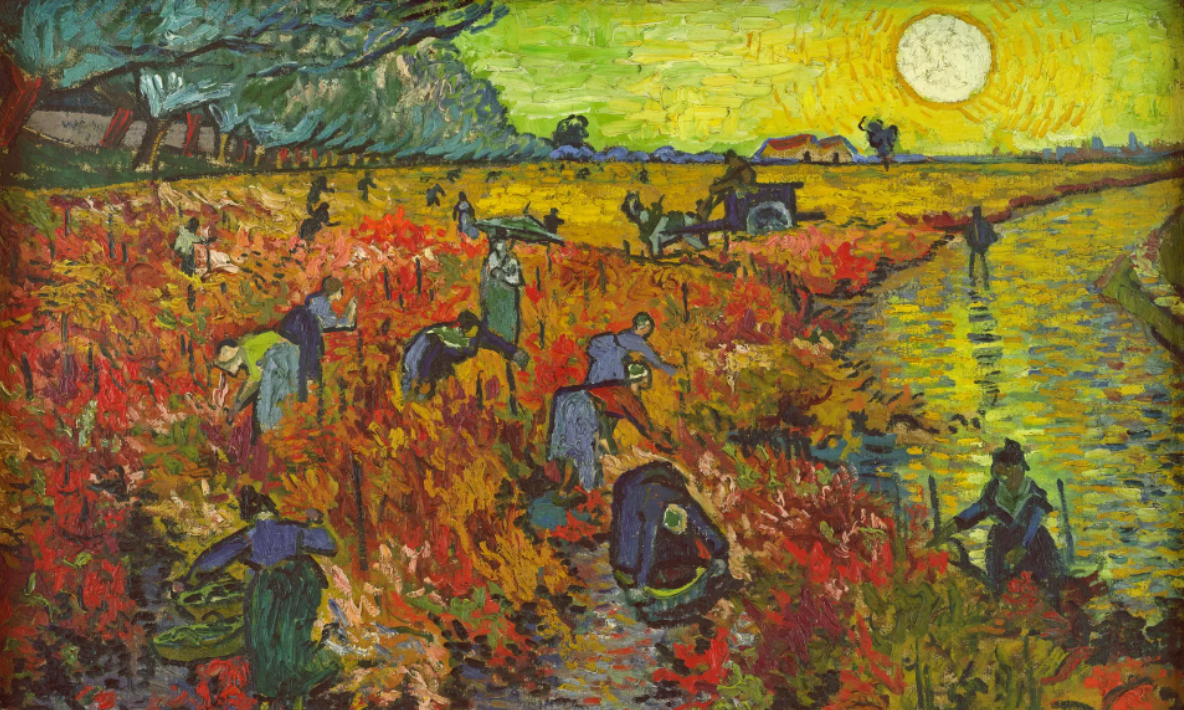

Van Gogh’s The Red Vineyard (November 1888) © Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Adventures with Van Gogh is a weekly blog by Martin Bailey, our long-standing correspondent and expert on the artist. Published every Friday, his stories will range from newsy items about this most intriguing artist to scholarly pieces based on his own meticulous investigations and discoveries.

One of the key aspects of the Van Gogh legend is that he couldn’t sell his art: he was a solitary genius, shunned by the artistic establishment. But this is not entirely true. In the last couple of years of his life he was beginning to win recognition, at least among the avant-garde.

It is often said that Van Gogh sold a single painting, with only one identified work going to a buyer. In March 1890 the Belgian artist Anna Boch bought The Red Vineyard (November 1888) at an exhibition in Brussels.

But Van Gogh may well have had a few more sales. There is tantalising evidence that one of his self-portraits was bought by the London dealers Arthur Sulley and William Lawrie. This revelation comes in a letter from Vincent’s brother Theo in October 1888, although the self-portrait is now lost.

Letter from Theo van Gogh to “Messieurs Sulley et Lori [Lawrie]/Londres”, 3 October 1888. © Published in M. Tralbaut, De Gebroeders Van Gogh, Uitgave van het Gemeentebestuur, Zundert, 1964, p.186

Early in Vincent’s artistic career, while living with his parents in 1884 in the village of Nuenen, he was commissioned to paint six landscapes for the dining room of a retired goldsmith, Antoon Hermans. Problems developed, and Hermans ended up giving him only 25 guilders (then around £2), which hardly covered his paint.

Van Gogh’s Potato planting (August 1884), commissioned by Antoon Hermans Credit: Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal

Two or three years later, in Paris, Vincent painted a portrait of a friend of his paint seller Père Julien Tanguy. He received 20 francs (then around £1). Although not conclusively identified, this is thought to be a portrait which was last recorded in 1927 and is known only from a black-and-white photograph.

Van Gogh’s Portrait of a Man (around 1887), probably depicting a friend of Père Julien Tanguy

On another occasion in Paris, Vincent exchanged a still life of smoked herrings for a carpet (a deal later recorded in correspondence with his brother Theo in March 1889).

In October 1888 Vincent referred in another letter to Theo that “a study”, presumably an oil painting, had been bought by the Parisian dealer Athanase Bague.

The final evidence of further sales is a condolence letter sent by Vincent’s aunt Cornelia van Gogh-Carbentus. She wrote to Theo in August 1890 that it must have been satisfying that his brother had succeeded in “selling a painting and in fact more than once”. So The Red Vineyard was not quite the only one.

But even if Van Gogh managed to sell a handful or two of his paintings, this still represents a minute proportion of the almost 1,000 that he completed. Despite encouragement from his avant-garde colleagues, most people simply rejected his work.

But what is astonishing, and has received surprisingly little attention, is the price of The Red Vineyard. It was bought by Anna Boch, sister of his friend Eugène Boch, for 400 francs (then around £16 or in today’s money around £500). At the time Vincent complained, surprisingly, to his mother that the price “isn’t much”. Perhaps this casual remark may have been Vincent’s way of telling her that he was finally going to make it in the art world.

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Eugène Boch (September 1888), brother of Anna Boch © Musée d’Orsay, Paris

But 400 francs was actually quite a considerable price for an up-and-coming artist. It was the equivalent of two months’ living allowance which Theo sent Vincent in Arles – or more than two years’ rent for the Yellow House, where he then lived. It was also a higher price than some paintings by Gauguin, who was beginning to achieve success (Theo sold two Gauguins for 200 and 300 francs in 1890).

So why the high price for The Red Vineyard? The arrangements were made privately by Theo, who was an art dealer working for the leading Boussod & Valadon gallery. We can only speculate, but perhaps Theo felt that it would be better for Vincent to sell a few works at a high price rather than start low.

Vincent was certainly fortunate to have a younger brother who was a successful dealer. It meant that Theo had the resources to provide Vincent with a regular allowance, which enabled him to paint. The two brothers endlessly discussed art, which gave them much in common. But it also meant that Vincent had a brother with the contacts and knowledge to sell his art, although this proved very challenging. But a start was about to be made.

In the last two years or so of his life Van Gogh was really beginning to win recognition. He exhibited at the progressive Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris: three paintings in 1888, two in 1889 and ten in March 1890. In January 1890 he showed eight works at the Brussels exhibition of Les Vingt, where The Red Vineyard sold.

I have tracked down more than 20 newspaper and journal articles which cited Van Gogh paintings in exhibition reviews in just the last seven months of his life, a record that would delight most struggling artists today.

Although most mentions were only a sentence or two, the critic Albert Aurier had penned an enthusiastic six-page article in the January 1890 issue of Mercure de France. Aurier concluded that Van Gogh is both “too simple and too subtle”—but he is understood by “his brothers, the true artists”.

The tragic fact is that Vincent’s potentially successful career was cut short by his suicide in July 1890. Had he lived into the 20th century, he would have probably become a successful contemporary artist, with his work being increasingly sought after.

Since then, Van Gogh’s prices have continued to spiral upwards. The artist who “failed to sell his work” is now among the most expensive.

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: the Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence(Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: [email protected]. Please note that he does not undertake authentications.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.