Senior Lifestyle Reporter, HuffPost

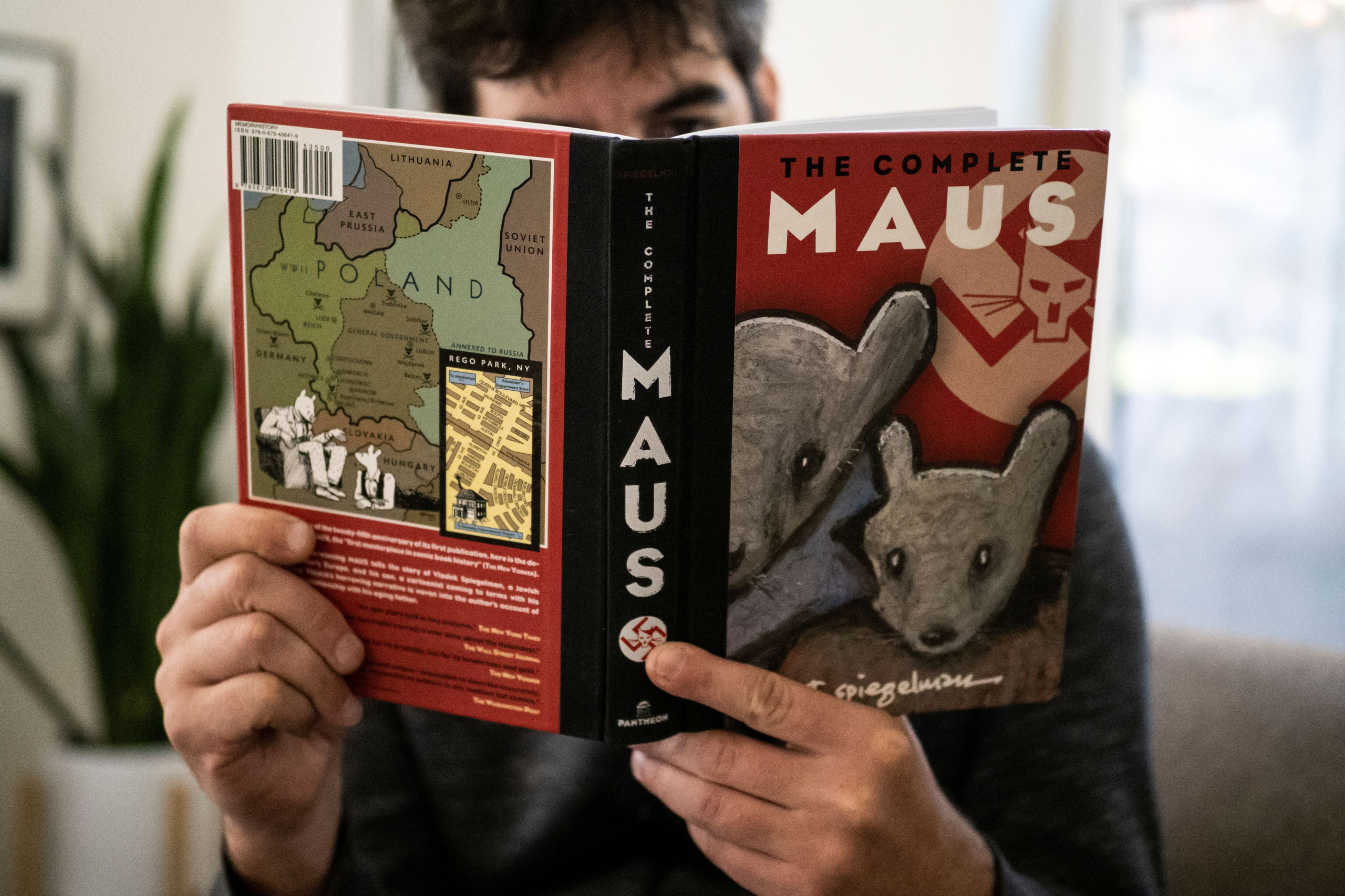

Last month, a Tennessee school board voted unanimously to remove the Pulitzer-prize winning graphic novel “Maus” from the district’s eighth grade curriculum on the Holocaust.

In the book, American cartoonist Art Spiegelman details his parents’ experience in the lead-up to the Holocaust and their imprisonment at Auschwitz, as well as his own generational trauma.

“Maus” isn’t the first book to get caught in the cross hairs of America’s latest culture wars: The American Library Association has seen an “unprecedented” number of book bans in the last year.

The books that received the most challenges in libraries and schools in 2020 were ones dealing with “racism, Black American history and diversity in the United States,” as well as those that center the experiences of LGBTQ+ characters, said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the group’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

And “Maus” isn’t the first book about the Holocaust to be called into question: In October, a Texas school district administrator advised teachers that if they have a book about the Holocaust in their classroom, they should strive to offer students access to a book from an “opposing” perspective.

Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” and books like Lois Lowry’s “Number the Stars,” a Newbery Medal winner about a young Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis to avoid being taken to a concentration camp, have been flagged in the past as inappropriate due to sexual content and language.

That’s primarily what caused the McMinn County board of education in Tennessee to nix “Maus” from its middle school curriculum, though It’s worth noting that the nudity is of cartoon mice.

Still, when reading the minutes of the school board meeting, Spiegelman told the New York Times he got the impression that the board members were essentially asking, “Why can’t they teach a nicer Holocaust?”

The ban came much to the dismay of the U.S. Holocaust Museum and also to educators, parents and students who see the book as a powerful teaching tool: “Maus” is basically a long-form comic book, so it’s not hard to see why preteens and teens gravitate toward it.

As one parent on Twitter put it: “When my son was 12, he was not academic, rarely read a book unless forced by a teacher, but loved ‘Maus’ books and spoke to me so intelligently and compassionately about the Holocaust and the impact it must have had on his Jewish friends’ families.”

As a learning disabled student, Kristen Vogt Veggeberg said the horrors of the Holocaust did not truly sink in until she read “Maus” at age 13. Vogt Veggeberg told HuffPost that she was and still is a visual learner; where traditional text accounts of the Holocaust and World War II failed, “Maus” succeeded.

“The images that Spiegelman drew ― of the gas chambers, the beatings of small children in the ghetto, the wealthy father-in-law screaming as he realized his privilege was not going to save him from Auschwitz ― stayed within my head as I went to my theatre rehearsals and academic decathlons,” Vogt Veggeberg, who’s now a writer and nonprofit director, wrote in an email.

Going through all of the illustrated pictures of the author’s family and finding out all of their fates was haunting and moving even for a self-interested teen, she said: “I was shaken at the idea that my entire family ― from my beloved grandma to my many, many cousins ― could be wiped off the earth.”

Educators shared their experience teaching “Maus” as well. Eli Savit, the prosecuting attorney for Washtenaw County in Michigan, wrote on Twitter that he relied heavily on the text when he was an eighth grade teacher in New York City Public Schools.

“My students ― learning about the Holocaust for the first time ― latched onto it,” Savit said. ”[They] deeply understood the Holocaust’s horrors. We took a field trip to the Holocaust museum at the end of the unit [and] every single 8th grader was solemn and well-behaved. (To emphasize: that NEVER happens).”

There’s profanity, nudity and suicide in the book, but we can’t whitewash the horrors of the Holocaust, Savit said. Six million European Jews were systematically and ruthlessly starved, worked or gassed to death, and some were even killed in medical experiments.

“Maus” quite literally illustrates the ugliness of the Holocaust in a way that is “both accessible and unavoidable,” Savit told HuffPost in an email interview.

“Adolescents in particular want to learn the truth,” he said. “They want to be treated as the emerging adults that they are, capable of making moral judgments; capable of understanding complexities; capable of being told the truth. The minute they suspect you’re shielding them from something, you lose them.”

Author and former middle school and high school teacher Karuna Riazi said she’s “appalled” that even something like the Holocaust is getting the both-side-ism treatment.

She told HuffPost that she worries that bans on books like “Maus” will mean some kids will never get the opportunity to read them.

“For many kids in America, their school libraries are the safest place for them to explore new ideas, read widely and freely, and without repercussions,” said Riazi, who is also the author of the middle-grade novel “The Gauntlet.” “These bans hit right where they will cause the most damage.”

Many teachers have shared author Gwen C. Katz’s viral tweets on the “pajamafication” of history. In the thread, Katz compares “Maus” to John Boyne’s concentration camp “fable,” “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,” since the latter is increasingly taught in middle school classrooms.

“The Boy in the Striped Pajamas [has none] of any of the parent-objectionable material you might find in Maus, Night, or any of the other first-person accounts of the Holocaust. It’s also a terrible way to teach the Holocaust,” Katz wrote, before listing out some of its major flaws:

First, obviously, the context shift. Maus, Night, et al are narrated by actual Jews who were in concentration camps. The Boy in the Striped Pajamas is narrated by a German boy. The Jewish perspective is completely eliminated.

Second, the emphasis on historical innocence. Bruno isn’t antisemitic. He has no idea that anything bad is happening. He happily befriends a Jewish boy with absolutely no prejudice.

Third, nonspecificity. The Boy in the Striped Pajamas turns a specific historical atrocity into a parable about all forms of bigotry and injustice. I’m sure Boyne thinks he’s being very profound. But the actual effect is to blunt and erase the atrocity.

Katz argued that the current “Maus” debate is “part of a broad trend of replacing the literature used to teach history with more kid-friendly, ‘appropriate’ alternatives.”

“It might mean replacing ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave’ or Solomon Northup’s ‘Twelve Years a Slave’ with modern historical fiction, for example,” she said.” “Wars, the Civil Rights movement, Apartheid: any ‘icky’ part of history can be a target.”

Indeed, the targets seem to be increasing by the day. As NBC News reported this week in the midst of this “Maus” controversy, hundreds of books have been pulled from Texas libraries for review, sometimes over the objections of school librarians.

In one alarming anecdote from the story, a parent in a Houston suburb asked the district to remove a children’s biography of former first lady Michelle Obama, claiming that it promoted “reverse racism.” (Reverse racism does not exist.) At another district just outside Austin, Texas, a parent proposed replacing four books on racism with copies of the Bible.

In school districts throughout the country, school librarians are spearheading grassroots efforts to fight back against book challenges.

Sometimes it’s as simple as putting out displays of what some might consider “touchy subjects,” which can include Black History Month and Pride Month.

Ira Creasman, a high school librarian in Colorado, said he was recently told that his school district had to disable comments on their Facebook post celebrating Black History Month because of a deluge of negative comments.

“That a display a school library put up for something like Black History Month might be considered a ‘touchy subject’ is stunning to me,” he told HuffPost.

Creasman is a big fan of “Maus” and believes it is appropriate for eighth graders, but he doesn’t discount the need for age-appropriate material for younger readers.

For example, he thinks Disney’s “Zootopia” does an “excellent job” of “illustrating the difference between explicit and implicit bias, but with the distance of the characters being anthropomorphic animals.”

“Easier entrances to difficult subjects are also helpful,” he explained. “We need both.”

In the wake of the “Maus” ban, Julie Goldberg, a high school librarian in New Allendale, New Jersey, put up a display encouraging students to pick up the graphic novel. (“Some students in the U.S. aren’t allowed to read ‘Maus’ in their school anymore,” the sign reads. “You are.”)

I rearranged the most prominent display shelf in our high school library.#Maus #bannedbooks #fREADom pic.twitter.com/llFB1kMQVa

Like Katz, Goldberg said she’s troubled by the “pajamafication” of history.

“Teenagers know when they’re being lied to, but younger children might not,” she said. “When we sanitize history, we create cynicism about everything we teach once students find out the truth.”

The librarian knows firsthand that her students are smart enough to grapple with the horrors of the Holocaust, and certainly so under the guidance of a teacher.

Goldberg grew up in Fair Lawn, New Jersey, a town that had many Holocaust survivors and children and grandchildren of survivors. Her father had friends and co-workers who were survivors, with numbers tattooed on their arms. Every year, the local public library had displays of photographs from the camps.

“I literally could not believe it the first time I heard that there were Holocaust deniers,” she told HuffPost. “It was so far outside my experience! It was like denying the Revolutionary War. I thought it must be a weird, sick joke.”

Nobody ever suggested that the children in Goldberg’s town were too young to know about the Holocaust.

“I feel like we were born knowing,” she said. “It’s the same for members of any marginalized group. When do Black children get to be protected from the knowledge of racism? Never.”

The idea that children from non-marginalized groups need to be protected from the knowledge of slavery, racism and anti-Semitism is confounding to the librarian.

“It creates a magic bubble of ignorance around white Christian kids that is unimaginable for any other group of children,” she said. “It elevates their innocence and comfort over everyone else’s reality.”

Of course, as Goldberg and other librarians across the country know, “soft censorship” like this isn’t anything new. In response to past censorship efforts, the American Library Association developed guidelines for schools to prevent the sudden and arbitrary removal of books.

Penguin Young Readers School and Library created a book challenge resources page for teachers, librarians and parents to consult if a book is challenged in their school district or library.

One positive to come of the current “Maus” controversy? People of all ages seem eager to read it. The decades-old graphic novel soared to No. 1 on the Amazon bestseller list in the last week.

As high school librarian and podcast host Amy Hermon told HuffPost: “Nothing compels students to read a book more than to tell them that the book is banned.”

Senior Lifestyle Reporter, HuffPost