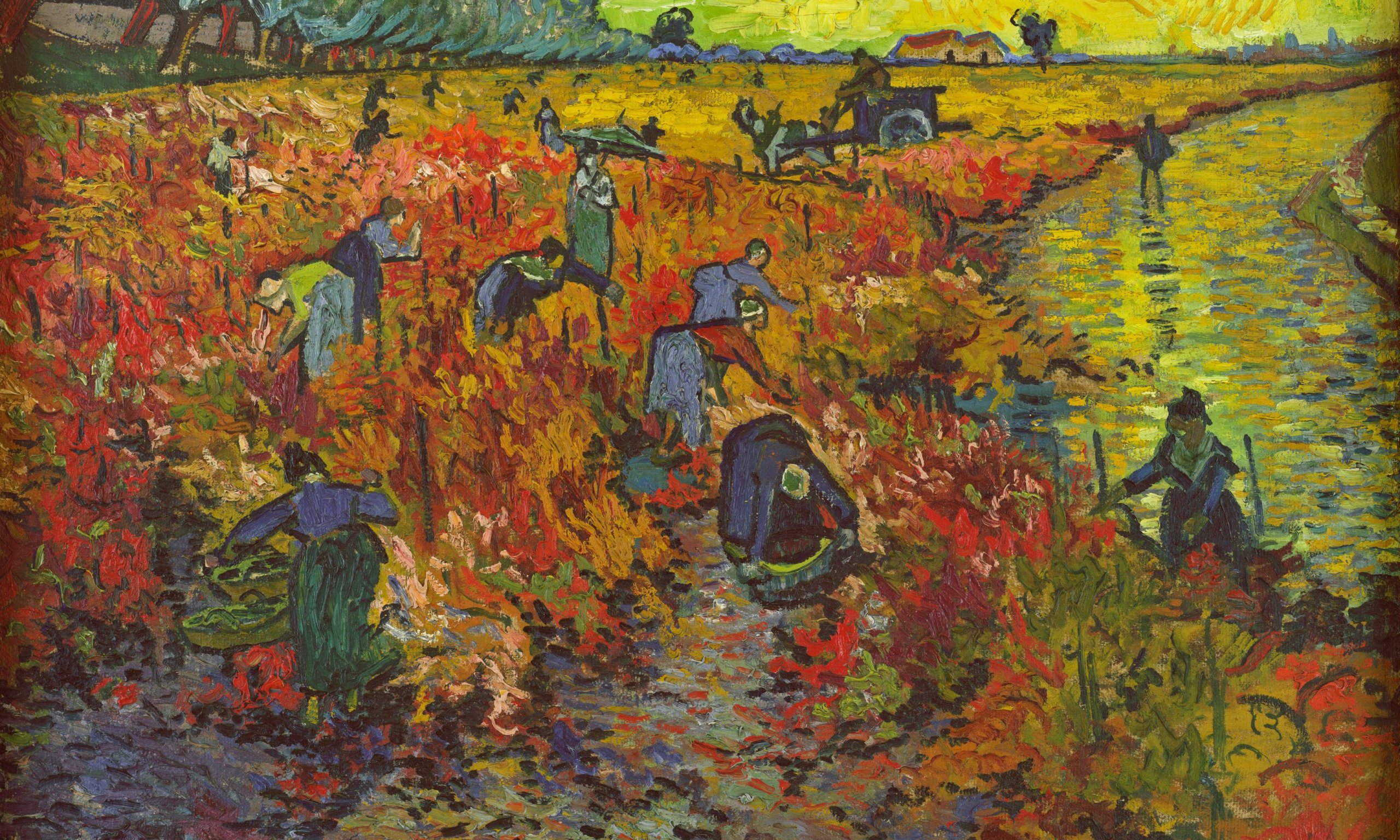

Van Gogh’s The Red Vineyard (Red Vineyard at Arles, Montmajour) (November 1888) Credit: Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Adventures with Van Gogh is a weekly blog by Martin Bailey, our long-standing correspondent and expert on the artist. Published every Friday, his stories will range from newsy items about this most intriguing artist to scholarly pieces based on his own meticulous investigations and discoveries.

The Red Vineyard is among Van Gogh’s most dramatically coloured Provençal landscapes, but it is also famed for being the only painting that the artist is certain to have sold. It went for 400 francs (then £16) at a Brussels exhibition in March 1890, four months before his suicide.

The picture is now in Russia, at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Recently the museum decided to conserve the picture, to ensure its long-term preservation. This led to the first investigation of The Red Vineyard using modern scientific techniques, unearthing fascinating discoveries.

The Red Vineyard in the Pushkin’s conservation studio, Moscow, 2021 Credit: Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Van Gogh came across the vineyard on a late afternoon walk with Paul Gauguin on 28 October 1888, five days after his friend’s arrival in Arles. Picking the grapes normally takes place in September in Provence, but the harvest seems to have been late that year. On around 11 October Vincent had written to his brother Theo: "There are bunches weighing a kilo, even—the grape is magnificent this year, from the fine autumn days."

Vincent described the vineyard scene he had witnessed with Gauguin: “A red vineyard, completely red like red wine. In the distance it became yellow, and then a green sky with a sun, fields violet and sparkling yellow here and there after the rain in which the setting sun was reflected.”

Although Van Gogh liked to paint landscapes outdoors, he completed The Red Vineyard back in his studio—using his imagination. Gauguin was then encouraging him to make his pictures more creative, less literal. No doubt the two artists discussed this vineyard scene on their return after the walk—over a glass or two of the local Provençal red wine.

Van Gogh’s fiery colouration is certainly extreme. The vines are much redder than one would expect, with Vincent describing it as the colour of the plant Virginia Creeper. On the right of the composition is what might appear as a river, but it is a road, glistening wet after recent rain. The huge sun, setting in a late autumnal afternoon, produces an eerily yellow sky.

In the upper left, the row of trees shelters a road running north-east from Arles. On the horizon, to the far right, one can just make out the distant ruins of the abbey of Montmajour, painted in light blue.

The Pushkin Museum’s examination of The Red Vineyard, sponsored by LG Signature, has revealed important details about how the picture was developed. Parts of the sun and sky are created from paint squeezed directly from the tube onto the canvas, with the artist sometimes using his finger to smooth it out.

A technical analysis shows that the colouration of the sky has been partly lost. Van Gogh used chrome yellow paint, which darkens with exposure to light. His original yellows would have been even brighter and still more dramatic.

Van Gogh also made changes to the composition. The man standing in the road in the upper right was originally a woman dressed in a skirt, white blouse and hat.

The prominent woman in dark blue bending over a basket, in the central foreground, was added later. The woman on the far right, by the edge of the road, wears the traditional costume of the Arlésiennes, the famed women of Arles. The Pushkin specialists suggest that she represents Van Gogh’s friend Marie Ginoux, who with her husband ran the Café de la Gare, just a few doors from the Yellow House, the artist’s home and studio.

The Red Vineyard has an unusual history. In April 1889 Vincent sent the painting to Theo in Paris. Describing it as “very beautiful”, Theo hung it in the Parisian apartment he had just moved into with his bride Jo Bonger.

A few months afterwards Vincent was offered the opportunity to exhibit a few paintings at an exhibition organised by the group Les Vingt in Brussels in January 1890. Among those he chose was The Red Vineyard, which he asked Theo to dispatch. At the show it was bought by Anna Boch, who kept it until 1907.

The two early collectors: Anna Boch (Théo Van Rysselberghe’s Portrait of Anna Boch, 1892) and Ivan Morosov (Valentin Serov’s Portrait of Ivan Abramovich Morosov, with a painting by Henri Matisse in the background, 1910). Credit: © Michele and Donald D'Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts; The James Philip Gray Collection (Jon Polak Photography) and Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Two years later The Red Vineyard was acquired by the avant-garde Moscow collector and textile factory owner Ivan Morosov. The asking price had risen to 30,000 francs, an indication of Van Gogh’s rapid rise to fame.

Morosov’s collection was nationalised in 1918, a year after the Russian Revolution. In 1919 he emigrated to Finland, dying in 1921. Initially Morosov’s paintings were kept in his Moscow mansion, which was turned into a public museum.

In 1948, The Red Vineyard was among the works transferred to the Pushkin Museum. However during Stalin’s later years it was not on display, since he regarded Modern French art as inappropriate for a Communist society. Following de-Stalinization, after the leader’s death in 1953, the Van Gogh once more went on show. The Red Vineyard has remained in Moscow and has not been sent out on loan for over 60 years.

The question of the painting’s condition recently came up with the organisation of a major exhibition of the Morosov collection in Paris. Eventually it was decided that the Van Gogh was too fragile to travel. The Pushkin director Marina Loshak admitted that it was “very sad” that this “ill” painting could not travel to outside exhibitions. Hence the decision to conserve it.

The exhibition The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art is now on at the Fondation Louis Vuitton until 3 April (with nearly 200 works of Modern art, but without The Red Vineyard). The show has proved a spectacular success, having already attracted over 800,000 visitors. The final figure could reach 1.2 million by the closure, an astonishing number, particularly during the pandemic.

One question that the Pushkin will now have to consider is the presentation of The Red Vineyard, which has been hung in an ornate gold frame. This frame probably dates from the time of Morosov’s acquisition, in 1909. It has become part of the history of the painting, so it is unlikely to be changed.

But a fancy gilt frame was not at all what Vincent had intended. In a letter to Theo he gave his own views on framing: “simple strips of wood nailed on the stretching frame and painted.” He drew an accompanying rough thumbnail sketch of the framed painting.

Vincent van Gogh’s quick sketch of the framed The Red Vineyard in a letter to Theo, 10 November 1888 Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The Red Vineyard is still in the Pushkin’s conservation studio, but it is due to go on display this summer in the museum’s presentation of the Paris exhibition, Brother Ivan: the Collection of Ivan and Mikhail Morozov (27 June-30 October).

Van Gogh’s companion Gauguin also painted his own depiction of the vineyard which they had seen together during their walk near Montmajour. But his version of the scene could hardly have been more different. Indeed, at first glance, it looks little like an autumnal harvest.

Paul Gauguin’s Human Misery (The Wine Harvest) (November 1888). Credit: Ordrupgaard Collection, Copenhagen

Gauguin’s painting, which he initially entitled Human Misery (November 1888), focuses on a melancholic woman whose figure was inspired by a contorted Peruvian mummy that the artist had seen in a Paris museum. Behind her are two rows of dense vines, with a couple of stooping pickers, set against a strong yellow-ochre background.

Van Gogh commented on Gauguin’s technique, saying that the composition with the grieving woman had come from his friend’s “head”, from his imagination. “If he doesn’t spoil it or leave it unfinished it will be very beautiful and strange,” Vincent commented.

Gauguin himself believed it was his “best picture” of the year—although its sombre title can hardly have boosted the chances of a sale. But like Van Gogh’s painting it, too, soon found a buyer—Emile Schuffenecker, a progressive artist friend. It was in the artistic circle of the avant-garde that the work of both Van Gogh and Gauguin was first appreciated—and found buyers.

Other Van Gogh news:

Yesterday, the Courtauld opened its exhibition Van Gogh Self-Portraits (until 8 May). The critics have greeted it with admiration, attracting five-star reviews from UK publications including the Times, Guardian, Daily Telegraph and Evening Standard.

Van Gogh: Self-Portraits at the Courtauld Gallery, February 2022. Photo: © Fergus Carmichael, courtesy of the Courtauld Gallery

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Francis Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: the Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: [email protected]. Please kindly refer queries about authentication of possible Van Goghs to the Van Gogh Museum.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.