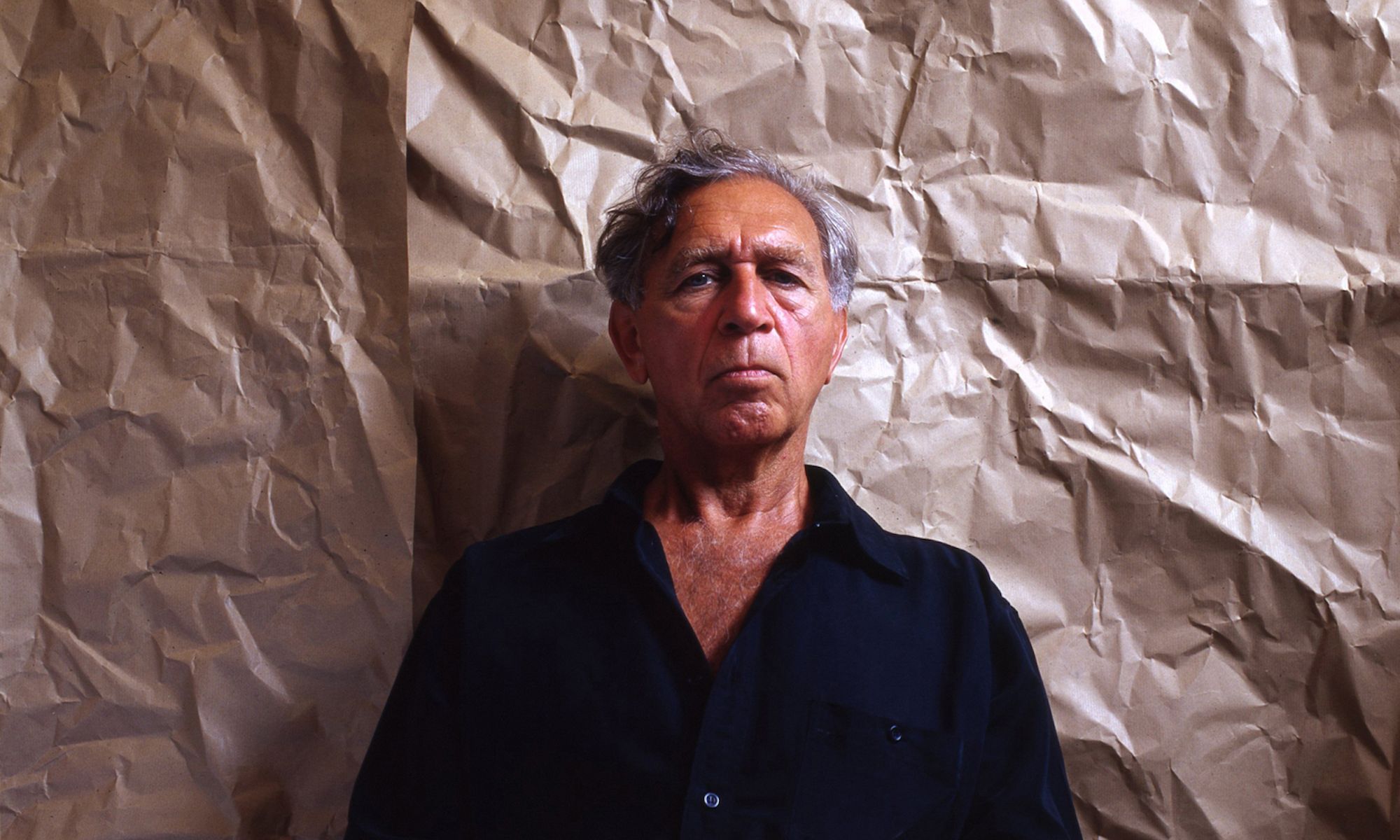

Jimmie Durham Photo courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York

The American contemporary artist and writer Jimmie Durham died on 17 November after battling various medical ailments, according to his Berlin gallerist Barbara Wien. Durham had lived outside the US since 1987, first in Cuernavaca, Mexico, and then Europe. He was living in Berlin at the time of his death at age 81.

“Jimmie Durham was one of the most inspiring artists I met,” says Wien, who worked with Durham for 22 years.

Durham was noted for his anti-monumental sculptures and his do-it-yourself aesthetic, as well as the use of humour and irony in his work. His legacy has faced criticism because of his many works that reference Cherokee identity, though he was not an enrolled citizen of any Cherokee nation and did not provide evidence of his Cherokee ancestry. (In the US, it is illegal under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 to misrepresent art and crafts as being made by a Native American tribal member.)

According to Anne Ellegood, the executive director at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (ICA LA), Durham contributed to the field of contemporary art through his singular works, his critical writings that “sought to question the systems and contexts in which authority was wielded and meaning determined”, and his support of other artists through teaching and mentoring.

Ellegood curated Durham’s 2017-18 retrospective, Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, which was organised by the Hammer Museum then toured to the Whitney Museum of Art, Walker Art Center, and Remai Modern in Saskatoon, Canada. She says Durham’s overarching project was to foster humanity. Or, as the artist put it: “Humanity is not a completed project.”

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait (1987) Image courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York

For Durham, “art was life, and art and activism were necessarily entwined”, Ellegood says. “Every action was intended to fight against oppression.”

Wit was ever-present in Durham’s work, Ellegood adds. “He used humour to pull you in, and then he clocked you in the nose with hard truths, highlighting the unforgivable violence embedded in the colonial project and the reality of how far we have to go to create a truly just world,” she says.

Born in Houston in 1940 to parents Jerry Loren Durham and Ethel Pauline Simmons Durham, Jimmie Durham emerged as an artist in the 1960s, having his first solo show in Austin, Texas in 1965.

He studied in Geneva at L’École des Beaux-Arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. When he returned to the US, Durham became an organiser for the American Indian Movement from 1973 until 1980 and served as director of the International Indian Treaty Council in New York. Afterwards he took up various causes, such as the Aids crisis and South African apartheid while becoming immersed in the 1980s New York City downtown art scene and co-editing the publication Art and Artists.

Kathleen Goncharov, the senior curator and executive director at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, was introduced to Durham’s work in the 1980s, and included his work in the recent exhibition Glasstress 2021 Boca Raton.

“He was really kind of brilliantly subversive in a good way,” Goncharov says.

Vincenzo de Bellis, the curator of visual arts at the Walker Art Center, calls Durham “a great thinker first and foremost”. “One of the most beautiful things about Jimmie was laughter,” de Bellis says. “The way he was able to laugh about others and himself, to be ironic about himself and not take himself too seriously while doing very serious and tough work is a great legacy.”

Jimmie Durham, Xitle and Spirit (2007) Image courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York.

De Bellis first met Durham in person in Como, Italy, in 2004, when Durham was serving as a mentor for emerging artists at the Fondazione Antonio Ratti. Later, they worked together when de Bellis was the Walker’s coordinating curator for Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World. De Bellis says one of his favorite Durham works is an early piece titled I want to Bee Mice Elf (1985), which was only included in the Walker’s instalment of the traveling retrospective.

“The word play is everything in the work,” de Bellis says. The piece features a brightly painted totemic figure adorned with bicycle lights and a rearview window, in addition to text that names animals and fantastical creatures in a coy statement about identity.

De Bellis calls Durham “an artist’s artist” whose oeuvre has been widely impactful. “A lot of artists have been influenced by his approach to sculpture and specifically the idea of anti-monumentality of the work,” de Bellis says.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World proved controversial, garnering criticism because of Durham’s identification as Cherokee. A cohort of Indigenous artists and curators met with representatives from the Walker to ask for changes about the way the museum presented Durham’s identity. One of the members of that cohort, Seneca artist Rosy Simas, said the incident, in combination with controversy over Sam Durant’s sculpture Scaffold (2012), instigated the beginnings of institutional change.

“Institutions are listening,” Simas says. “Not entirely, but the conversations are openly happening. We are talking about very large cultural institutions who have been very siloed, and also have called their own shots.”

The controversy did little to dampen Durham’s renown, though it did complicate the ways his work is presented. “It was very painful for him to be put under this scrutiny,” de Bellis says. “On the other hand it was very painful for many people and institutions that were in the midst of it. It’s not an easy solution. I believe Jimmy is a very important artist, no matter what his background is.”

Durham is survived by his partner, the artist Maria Thereza Alves.