Gender Reporter, HuffPost

Dr. Joshua Yap has barely had a second to breathe since Texas passed the country’s most extreme abortion restriction.

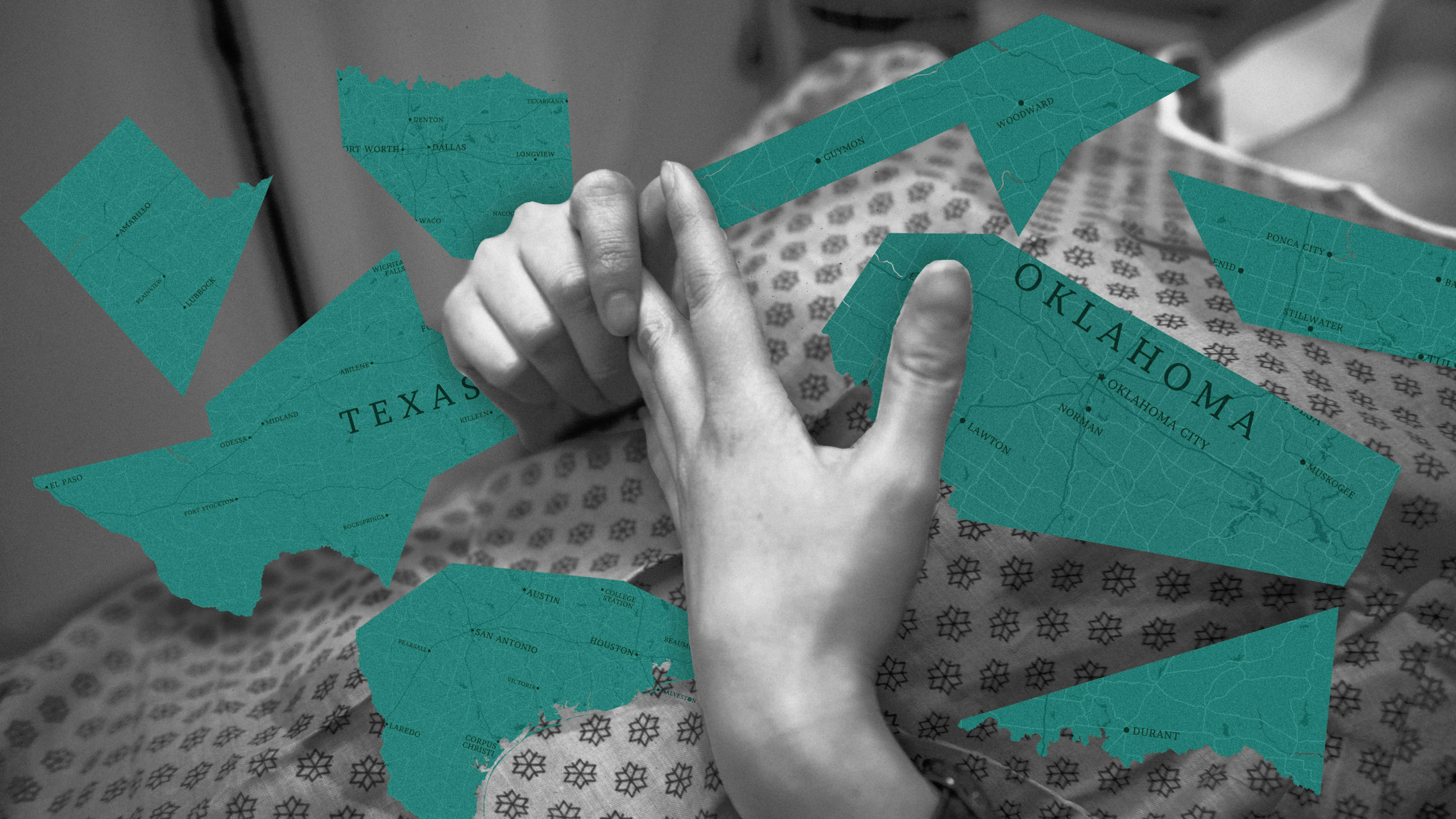

Yap works at Planned Parenthood’s Tulsa clinic, which was already extremely busy before S.B. 8, a radical anti-abortion law, took effect in neighboring Texas on Sept. 1. Texas had effectively shut down clinics during the pandemic, so a large number of patients were already crossing the border to obtain services. But when S.B. 8 became law, Yap ― who is the only abortion provider at his clinic ― began working nonstop to accommodate the influx of Texans.

S.B. 8 banned abortion after six weeks of pregnancy and deputized private citizens to enforce it. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the law last week, and the majority of the justices hinted that they may allow legal challenges to it. But the legislation has had a significant impact on people seeking abortions in Texas: Many are leaving the state to receive care while other less privileged people are being forced into giving birth.

Before S.B. 8, Texas provided an average of 53,000 abortions every year. Now, the four clinics in Oklahoma are picking up the pieces by providing care for both Texans and Oklahomans. The two Planned Parenthood clinics in Oklahoma saw 35 patients from Texas between September and November 2020 — and 653 Texans during that same period in 2021.

“Trying to absorb all of these additional patients has been hard,” Yap said, noting that Oklahoma is a small state with only a few providers.

As such, Yap feels a heavy responsibility to accommodate as many patients as he can. And that pressure takes a toll on him and his staff. “I worry a lot,” Yap said. “What if I get sick or if I become incapacitated? I can’t take a day off knowing that people are driving, sometimes eight to nine hours, to get to our clinic here in Tulsa.”

Yap grew up in Southern California, where he later attended medical school. He then moved to the Bronx in New York City, and did his residency in family medicine.

Oklahoma has been a big change for Yap and his partner, and safety concerns are always looming. “It’s not just safety concerns from being an abortion provider, but being a queer person of color providing abortions in Oklahoma,” he said. “We’ve had some people outside our house yell ‘faggot’ at us. There are many layers to what it means for me to be a provider here for me.”

Here’s what a typical day for Yap looks like, as described to HuffPost, and what it’s like to be a medical refuge in an increasingly restrictive and even hostile environment for reproductive care.

Yap usually starts his mornings by feeding his two chickens, Bertha and Karmela (“Something I acquired in Oklahoma,” he quipped). He slaps some water on his face, gets dressed and heads to work.

He usually calls ahead to alert the clinic’s security staff that he’s on his way. “Because of all of the safety concerns, I do try to be as careful as possible,” he said. “So I let them know that I’m on my way each morning, and when they see me on the cameras [outside of the clinic] they come out to greet me in the parking lot.”

Without fail, Yap is met with anti-abortion protesters outside the clinic. There are typically between five and 15 people gathered, but the crowd size fluctuates. One day, he said, there were about 40 people holding a mini-sermon on the lawn across from the clinic’s parking lot.

“The way our clinic is built, there is a public alley between our parking lot and our clinic ― meaning protesters are allowed to walk through that alleyway. And protesters have become a lot more bold recently: walking up to patients and staff members to talk to them or hand them things,” he said.

“I worry a lot. What if I get sick or if I become incapacitated? I can’t take a day off knowing that people are driving, sometimes eight to nine hours to get to our clinic here in Tulsa.”

As he reaches the clinic, Yap sometimes meets the protesters head on. Yap, who has various gender expressions, said he often attracts direct attention from protesters who assume he’s a patient.

“Some people just say something as simple as, ‘You don’t have to work here’ or ‘You don’t have to go in there,’” Yap said. “One that really pissed me off was when someone said, ‘Honey, you don’t need to go in there to get hormones. You don’t need that, it’s going to hurt your body.’ Making an assumption of why I’m going into the clinic.”

“These protesters, who are primarily there to harass people getting abortions, are also harassing other patients and other people for other issues that they shouldn’t have any hand in.”

Their presence has instilled fear in the staff at the clinic. Yap recalled a car following him for at least 15 minutes one day after he left work.

“I just kept driving and driving in different directions, and they kept following me,” he said. “Eventually, I had to pull into a busy parking lot and just hang out there until I couldn’t see them anymore, then I went home. I don’t know necessarily if that was an anti-abortion activist, but the terror of that potentially happening was really present and really uncomfortable.”

More recently, one protester stood outside of the clinic with a rifle. Under the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, it’s a federal crime to use physical force or the threat of physical force to prevent patients from entering clinics. But because of open carry laws in Oklahoma, clinic staff members couldn’t call the police.

“They were just standing in the public space area outside of our clinic. They just held up a phone as if to record people,” Yap said. “We didn’t know what they were going to do in that situation. Obviously, it was meant as a scare tactic. And it was very terrifying. It really served as a reminder that there are people who are very angry at someone like me.”

Planned Parenthood’s Tulsa clinic opens and closes at different hours throughout the week so that Yap and his staff can accommodate as many people — and their different schedules — as possible. On Wednesdays, the clinic is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

“Once you enter the clinic, on the busy days, there are usually a bunch of people in the waiting room already,” Yap said. “We often triple- or double-book our schedule to be able to accommodate as many people as possible. Since S.B. 8 … as much as 75% of my patients are from Texas. So, oftentimes, we have more patients from Texas than we do from our home state of Oklahoma.”

On average, Yap sees about 30 patients a day. The clinic also offers birth control, STI testing and other sexual health care services, but the majority of Yap’s days are focused on abortion care. His schedule accommodates around 12 surgical abortions a day, but he’ll sometimes see a few more patients. On one of the busiest days, Yap estimates that about one-third of the clinic’s patients had surgical abortions, while the rest received medication abortion.

“The surgical procedure for an abortion, in most cases takes, anywhere between five and 10 minutes. It’s really fast,” he said. “The bulk of the time is often explaining to patients about the procedure and giving them all of the appropriate information, telling them that they are complying with state laws. Sometimes, we need to get labs done. But, oftentimes, the procedure itself only takes up about 10 minutes of a four-hour visit that a patient has.”

Some states, like California and New York, allow physician assistants to provide medication abortions. But Oklahoma state law requires that only doctors of medicine and doctors of osteopathic medicine provide abortions, both surgical and medication — which means Yap is the only person who can provide abortion care to all of these patients.

He often does not have time to take a lunch break.

“Oftentimes, we have more patients from Texas than we do from our home state of Oklahoma.”

Aside from the actual abortion procedures, most of Yap’s day consists of him and his staff sitting with patients.

“Sometimes there are moments where patients have to grieve a little bit, not necessarily for their abortion, but for the whole process they have gone through,” he said. “I remember one patient had to rant: She was so grateful that she could get an abortion with us, she was so relieved that this could happen still, but she was so angry that she had to come all the way from her home in Texas where she lives near an abortion clinic, but they couldn’t provide her an abortion.”

Another patient, he recalled, said they had started their drive to Oklahoma — about nine hours — after they finished work around midnight so that they’d make it to their appointment on time.

“Then they had either a medication abortion or the procedure and then they drove all the way back home,” Yap said. “That is a long 24 hours.”

Patients aren’t the only ones who are affected by the burden of traveling for an abortion.

“We had one person ask for an excuse note for school. We do write excuse notes for patients all the time. So we said, ‘Yeah, we can do that.’ But then she clarified, ‘Well, actually it’s for my kids,’” Yap said. “When we asked why she needed a note for her kid, she said she had to take her kid out of school that day in order to make it to her appointment in Oklahoma. She couldn’t find child care at home in Texas. So she had to bring her kid with her.”

Since S.B. 8 doesn’t provide exceptions for sexual assault or incest, Yap and his staff are often the first people patients confide in about those experiences. In addition to medical care, Yap and clinic staff are providing a safe space and much-needed emotional support to many patients walking in by themselves.

“Visits are taking longer now because our staff are sitting and providing space for patients as they vent about what they are going through in Texas,” he said. “We are the ones, maybe the first, that someone opens up to as a safe place. Sometimes my staff need to take some time to recenter after an intense moment, which is so important but also means that there will be some more delay throughout the day.”

Because Yap is the only provider at the clinic, he has to do all of the medical charting for each patient he sees. This means he sometimes stays at the clinic for an hour or two after closing just to complete his charts.

Yap is also required to do some extra paperwork — a policy that he said is often created by anti-abortion lawmakers who are simply trying to make it harder for physicians and clinics to continue providing abortion care.

“All of this adds hours to our day,” he said. “If we didn’t have all of these useless requirements from the government, our time could be better spent providing care to patients.”

And then there are days where Yap and clinic staff stay longer to help overflow patients.

“There are days we spend up to two and a half hours just being there for a patient who showed up late or without an appointment,” he said. “We do our best to accommodate them because it’s not as simple as saying, ‘We can reschedule.’ We can’t turn them away after they made all that effort to get to our clinic.”

After a long day at work, Yap likes to unwind by taking Spanish classes or cooking with his partner. (“I’m an experimental cooker, I cook all sorts of things.”) He sometimes hangs out with his staff, who he describes as his “rock.”

“We have some of the greatest people here, who have been faced with some really hard times. They’ve been amazing to work with and commiserate with,” Yap said. “I moved here right before the pandemic, so it was hard to have a social life outside of work. A lot of them are who I’m most close to in Oklahoma.”

Most recently, he was part of a local production of the musical “Dreamgirls.” Rehearsals were on Wednesdays at 6 p.m., but sometimes ― if he was working after hours at the clinic ― he would be late or miss rehearsal altogether.

“I try to live a normal life outside of all of this,” he said. “It’s not like my life is only about abortion.”

Yap is a bit of a night owl. And after such a long day, he typically gets little time to himself.

When reflecting on the best part of his day, Yap pauses thoughtfully before responding: “The care of abortion is really an individual thing, and right now I think what’s gotten lost in this national conversation about the law is that personal experience. When patients tell me how grateful they are, it reminds me how meaningful this work is to someone on that individual level. Those are the moments that remind me why we do what we do.”

Gender Reporter, HuffPost