Guest Writer

I was confused.

The instructor of my Zoom children’s book writing class often used her own books as examples for the students. However, the book she’d just shown us, featuring a brown-skinned main character, was written by someone with a distinctly South Asian name. I then heard the words “pen name” and my breath slowed.

Is this what I think it is?

It was. The POC author of the book was actually a blond white woman who didn’t seem to think there was anything wrong with her act of brownface.

The other seven students, all white women, continued smiling, taking notes and asking questions. I spent the rest of the hour staring ahead, trying to avoid looking at my Black face staring back on the computer screen.

After class, I lay down on my living room sofa.

Is this a big deal, or am I making it a big deal? I asked myself.

She’s a nice person. She didn’t mean any harm.

I didn’t trust my own feelings and needed help. The Facebook post I crafted was simple and direct, explained what had happened in a couple of sentences, and asked other people if I was overreacting. The responses ― 55 of them in total ― started coming within minutes.

“You have to out her.”

“One of the problems is we don’t speak up when this happens.”

“I would have had a hard time not saying what was on my mind.”

I didn’t want to speak up, though. I also didn’t want to not speak up. What I wanted was for the situation to disappear, to not have to think about it or have to choose between being seen as The Angry Black Man or seeing myself as an Uncle Tom.

Growing up, I rarely thought about race, which sounds absurd, considering my small Western Massachusetts hometown is almost all white. Racism in Great Barrington was often excused, ignored or dismissed. The very liberal upper-middle-class-y folks who lived in what was voted “Best Small Town in the USA” couldn’t possibly be intolerant. After all, we have rainbow-colored “diversity” crosswalks.

W.E.B. Du Bois was born in Great Barrington in 1868. I never read his books, or those of almost any Black author, until my 30s. I had a fear of reading experiences similar to my own, though I didn’t realize it at the time.

When I finally read Du Bois’ “Souls of Black Folk,” my truth was on the first page. He wrote about giving a middle school classmate a calling card: “The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card — refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others…”

I was having trouble taking it in. The exact same thing had happened to me.

It was when I was in third grade. I passed a note to my crush, M, who wore skirts with sneakers and ankle socks and had always been friendly to me. She looked at my scribbled letter, then at me.

“Thanks, but my parents would never let me date a nigger,” she told me matter-of-factly.

I wish I had called her out, yelled, or told the teacher, but I didn’t. Instead, I smiled a smile meant to convey, Silly me! Of course you wouldn’t want to date a nigger. What in the world was I thinking! I was letting everyone know I wasn’t a problem. I trying to signal I was in on the joke.

I was also “in on the joke” when I climbed an exercise rope and, from below me, I heard my gym teacher making grunting monkey noises.

I was “in on the joke” when a girl told me parts of my face were attractive, using her hands to exclude my wide nose and thick lips.

I was “in on the joke” as a glob of green phlegm, spat at me by a “friend” who was now disgusted by my Blackness, dripped down a favorite sweater.

I now feel blister-burn rage when thinking about those incidents. The anger is directed at my antagonizers, yes, but also sometimes at myself for the silence that followed their actions. And now, faced with what I’d discovered about my writing teacher, I felt these familiar conflicting emotions churning inside me.

The irony of the whole situation was that the children’s book I was writing was about empowering POC kids to acknowledge and challenge subtle types of racial bias, and here I was struggling to do the same thing.

After several hours of hesitation, I emailed her. She responded two hours later.

“Sorry state of affairs in publishing.”

“I came up with a list of names, some obviously ethnic.”

“I wanted to show representation.”

I didn’t know where to direct my emotions: at her, the publishing industry, or the world. Or all of them. Instead, I numbed out by scrolling through my social media and then went to bed.

Another email from her arrived in the morning, with “apologies for any pain [I] caused” and letting me know she didn’t “condone the actions of the publisher/editors and [her] own cluelessness.”

See, she was sorry.

I told her I was still “processing my feelings.” I closed the email with “Best, Delano.”

It’s not easy rereading my emails to her now. The language I used makes me feel a little bit like a house slave thanking massuh.

Because, the thing is, I do know the power of speaking up.

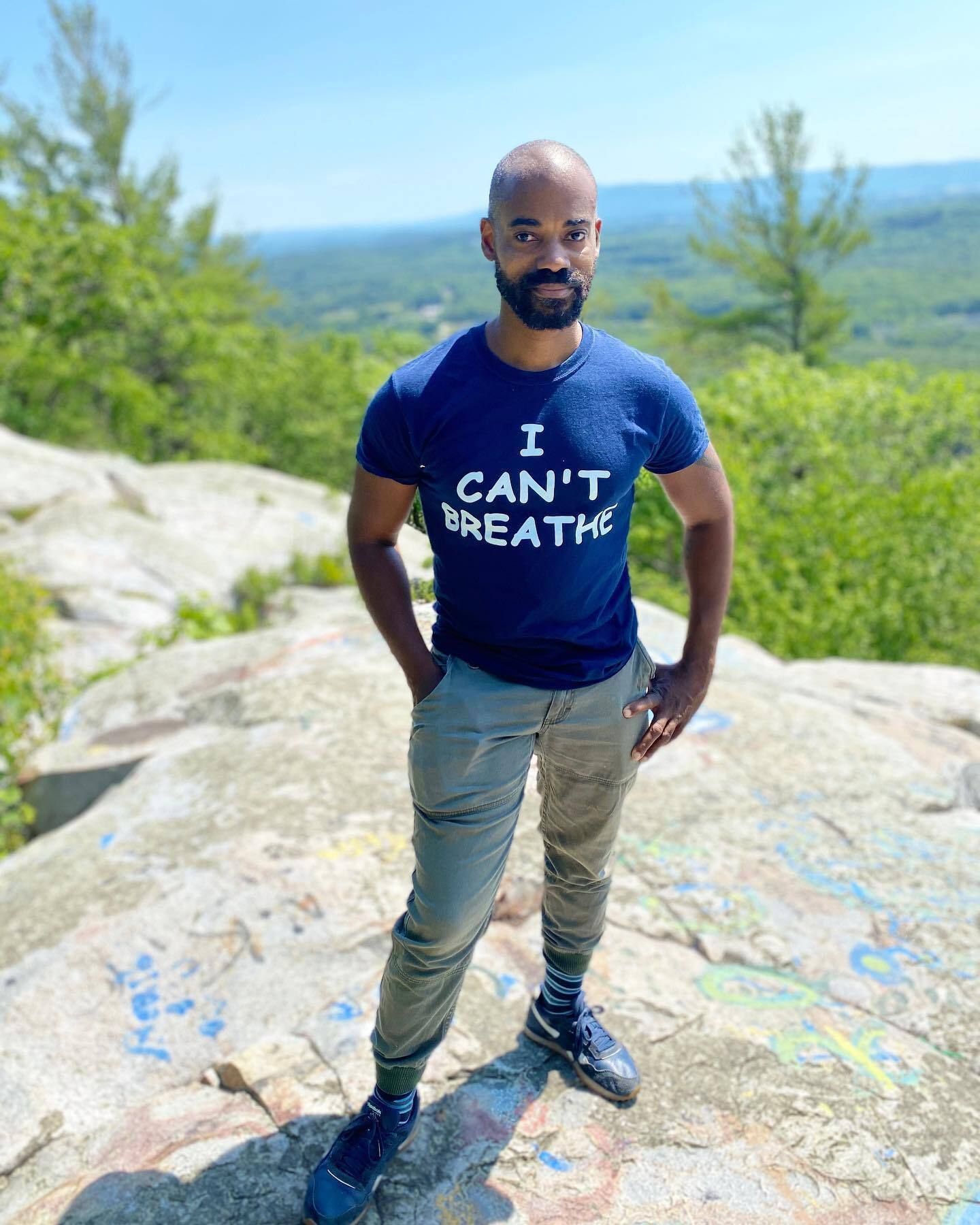

I spent the first five months of the pandemic with my recently widowed mom in Great Barrington, so I was there when Black Lives Matter exploded. We even held a BLM rally outside the Town Hall on Main Street.

It was exactly what I thought it would be.

People strolled around with smiles, taking photos to be later posted on their social media, while white people with dreadlocks played drums. Some old friends greeted me with elbow bumps but soon became visibly uncomfortable when I mentioned what it’d been like growing up in the town. One gave me a mini-speech about what the worldwide BLM protests meant, ignoring the opinions and lived experience of the Black person in front of them.

Returning home by walking the same railroad tracks I’d walked as a kid, I decided to write a letter.

I was surprised the county paper printed it, and more surprised that it was shared online over 1,000 times.

Three of my “microaggression” poems ― the rawest poems I’d written ― were published that same June, with positive reviews and responses. I got messages from Black people, thanking me for putting my and their experiences into the world. I was finally connecting to others, and myself, by being honest about my racial traumas.

An editor asked me to write a children’s book, something I’d never even remotely considered. All those things happened because I spoke up and spoke loudly, so why was I now struggling with doing the same thing?

A large part of 12-step recovery programs involves breaking down resentment toward people, places and things in order to see how they contributed to our addictions. I came into recovery believing that I wasn’t overly affected by racism, and then discovered my life was instead defined by attempts at avoiding the subject.

I discovered that much of my resentment was aimed at myself for not expressing real emotions for fear of what others might think of me. I’d then feel shame, which I numbed through drugs, alcohol and sex.

For example, a couple of months after moving away from Great Barrington, I found myself in handcuffs. I was the one who’d summoned the police for help with a taxi driver who’d decided he was tired and no longer wanted to drive me to my destination. When I protested, saying I didn’t want to get out of the car because I didn’t know where I was, he raised his fist and said, “I’ll drop you off where I want, boy, and you’re gonna give me my fucking money.”

I ran out of the car and flagged down two police officers who looked at both of us, and before anything was even said, put handcuffs on me. The taxi driver laughed at me behind their backs.

“I came into recovery believing that I wasn’t overly affected by racism, and then discovered my life was instead defined by attempts at avoiding the subject.”

A Black woman passed by, glancing my way before turning her head. In that brief moment, I saw sadness and disappointment in her eyes. I wasn’t able to control how she, or anyone else, translated me. My speech, clothes, background: Nothing could save me from the looks that let me know how I was seen as a problem.

The cops eventually removed the handcuffs and let me go ― but not before making me pay the driver. I didn’t tell anyone what happened.

Then there was the time a car full of teenagers threw a fountain soda at me while yelling “nigger.” I walked over a mile home in the August humidity with my skin covered in the sticky cola. Then I showered away the evidence, turned on the TV, and didn’t think about it again.

I became a master at splitting myself in two.

Du Bois came up with the concept of “double consciousness,” which is “[the] sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” that is internalized by Black people. I know the feeling well. I believed I was responsible when the only remaining seat in the rush-hour subway car was next to me yet remained empty. Women instinctually clutched their purses on the sidewalk because I believed I’d failed to make them feel safe.

Always being aware of how your skin is seen makes it hard to relax in that same skin. This conditioning was drilled into me from birth and, in some ways, it also protects me. It can save me from a bullet in the chest if I go for a jog in the wrong neighborhood at the wrong time.

I emailed my teacher back. I told her I wouldn’t be coming to the last class.

Her response came quickly. “I will be more mindful of my comments in the future … very sorry if I behaved insensitively to you.”

It was never about me, or my hurt feelings, but about this way of responding, this refusal to ask uncomfortable questions about the conditioning behind actions and thoughts. Did I say any of this to her? No. I didn’t say anything.

I don’t know what happened in the last class, or if she mentioned my absence to the other students. If she did, how long was it before they all pivoted back to discussions of plot lines and structure, ready to move on from that blip in their consciousness?

If she didn’t mention my absence, then what was the point of the apology except to make herself feel better?

None of the other students reached out to me, though I was still on the class email chain for another week, and I read their plans to keep in touch.

I received another email the following day from my instructor.

“Please let me know what you need to feel this situation has resolved or at least improved … I am happy to give you some extra reading/feedback time at no charge if you feel this would be helpful.”

She was congratulating herself for being good and offering up her knowledge as reparations. I didn’t respond.

I’ve had many deaths in my life recently. My dad. My uncle. My aunt. Two friends. I’ve seen the relentless display of murdered Black bodies on the news. Grief isn’t a linear progression; one day I can feel at peace, and the next day I’m curled into a fetal position on my bed.

Speaking up about racial aggressions isn’t linear, either, I now understand. Yesterday’s in-your-face confrontation can be today’s silence.

When the world tells you your existence is a problem, it’s OK to sometimes retreat from one more example. I could be angry dozens of times a day, and sometimes I am, but I must face the consequences of that anger and the effect it has on my mental health.

A white now ex-friend, an activist, called me out for not constantly posting about social injustice on my social media. He couldn’t understand that if you’ve been trained to always be suited in armor, it gets heavy sometimes. He said my problem was not understanding he was the kind of white person who would “put his body between Black people and the enslavers of Black people.” I didn’t have the energy to respond.

I still do not know what the right answer was in regard to my teacher and what she did. Writing about that experience feels like one way to call attention and hopefully raise awareness about these acts. They aren’t innocent, even if the perpetrator had “good intentions” or “wasn’t aware” of what they were doing. They have consequences.

But I am certain that my silence at that moment didn’t equal passivity. I’ve realized that when these things happen, I’m focusing on my breath, connecting to how emotions show up in my body, and trying to dismantle the legacy of shame that has been passed down to me through generations of enslavement and humiliation. Being compassionate to myself, while knowing that I’m doing the best that I can at any given time, is stopping that cycle, and, for me and for now, that’s enough.

G. Delano Burrowes is a Brooklyn writer and visual/performance artist whose work explores race, sexuality, and identity. He is currently working on a memoir about overcoming addiction, shame, internalized racism and lack of rhythm. You can reach him on Instagram at @theodorehuxtable and on Twitter at @DelanoBurrowes.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

Guest Writer