The David C. Driskell Center presented African American Art: Increasing Resources for Education in the 21st Century at the annual conference for the Association of African American Museums (AAAM), held August 8th through 11th, in Hampton, Virginia. The main focus of the presentation, by Dorit Yaron and Stephanie L. Smith, was on our IMLS (Institute of Museum and Library Services) funded digitization project and how that fits into the overall educational mission of the David C. Driskell Center. Fellow graduate student Tamara Schlossenberg and I were invited to attend the conference and participate in the presentation.

Many different types of institutions came together for this conference. Creating Access through Digitization of Collections, a session moderated by Mark Isaksen of IMLS, featured reports on funded digitization projects for manuscripts, sound recordings, and photographs, respectively, at three different archives and museums, with varying missions; Xavier University of Louisiana, the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, and the Withers Collection Museum and Gallery in Memphis. The session focused on how institutions can expand their reach (and visitor experience) through digitization, and the crucial aspect of securing funding for these projects.

Another session I attended, Using Technology to Remember the “King” of Jazz and How Your Museum Can Do The Same!, led by representatives of the Nat King Cole Museum at Alabama State University, focused on delivering digital content and more broadly speaking, technology as a complement to the traditional “house museum” concept and how other institutions might better engage visitors through technology. A lively Q&A following that presentation made it clear that museums, even travelling exhibitions, are grappling with how to improve their visitors’ brick and mortar and virtual experience through technology. While challenges, cost chief among them, persist, the overall spirit was one of optimism. Digitization is a way to assert museums’ relevance, not merely a game of catch-up. These projects are not just about satisfying pent-up demand for digital content, they represent a new direction and afford new opportunities. This insight made me feel even more confident and excited about our digitization project at the Driskell Center. We have already seen increased engagement with scholars as a result.

The conference was an opportunity to see the Driskell Center in the broader context of the African American museum world. Furthermore, it was an occasion to reflect on the Center’s mission as an extension of Professor Driskell’s career as artist and educator. Through the photos in the Driskell Papers collection, a powerful theme emerges. His student days; his teaching at Howard; at Fisk; and the University of Maryland, along with countless workshops elsewhere, are represented on a par with his personal artistic achievements, seamlessly. Likewise, the David C. Driskell Center tries to achieve that balance. This digitization project could be solely devoted to preserving artistic achievement but that objective is part of a broader aim to educate this and future generations about the African and African American contribution to world art. The David C. Driskell Center seeks not only to represent Professor Driskell’s personal commitment through digitization, but to embody it and move it forward. Our digitization effort advances our educational mission on multiple fronts. Students gain skills working on the project. And other students and scholars, within and beyond the University of Maryland community, have increased access to the Driskell Center’s resources and their work multiplies its impact.

This post was written by David Conway, Graduate Student in the University of Maryland MLIS Program and The David C. Driskell Center

As we mentioned in our last post, the digitization project for the David C. Driskell Archive is in full swing. But right around that time, we hit an impasse. I’ll call it an “impasse” because that’s what it felt like (to me) at the time.

We were handling some requests from researchers for JPEGs of some of our photographs and transparencies to be reproduced in scholarly publications. This led to some critical reflection on the overall quality of the scanned images we had been producing as part of our larger digitization project. It’s misleading to compare an original photographic print source with a scanned digital image rendered on a computer screen. And, there’s a remarkable inconsistency across screens, even in an office like ours, using computers and monitors of similar make and age. But, when we really looked at some of our digital surrogates, we just weren’t satisfied with the quality of the digitized product in relation to the original. Specifically, many seemed to have a haze of sorts over the image and at the same time, oddly enough, the texture of the source was often overrepresented in the scan. It seemed that some scans did a better job of revealing the flaws in a print, than the content of the photo. Crinkles in an old print, even stains on the surface, were showing up better in scans than they did in the originals. This was particularly evident with Instamatic-type matte finish prints from the 1970s that have a bumpy texture you can feel (and see). Scans of photos were often too bright or bleached-out looking and transparencies too dark or dull. We thought we could do a better job of representing our archives.

One of the more intriguing aspects of working in an archives associated with a museum or gallery is the intersection of two perspectives on (re)presentation; one deriving from the art world and the other from the archives world. Museums and archives are both, for all their differences, memory institutions engaged in curation. Curatorial decisions are part and parcel of this and every digitization project. How will we best represent our collections? How will we tell the story of David C. Driskell’s legacy and the Center that bears his name?

I’m a neophyte in both of these worlds but as an aspiring archivist I try to bring the values of the profession to my work. So my perspective is that we should produce the most faithful representation of an object in our collection. But, as we began to think more about why we were digitizing—which is ultimately to tell Professor Driskell’s story, which is also the story of how African American art came to be recognized, appreciated, collected and taught about—we knew we had to produce better images for the scholars who will continue his work for future generations. Thus returning to the idea of curation as it pertains here, we need to present quality images that are not only more accessible in digital form but that genuinely encourage teaching.

Without dwelling on technical details here, what I discovered in the course of my research on the topic is that the mostly right-out-of-the-box settings we were using on our Epson scanner weren’t producing the results we needed to tell our story. But, we needed to find a range of settings that could be applied consistently across material, so that we weren’t changing settings for every image. It was a journey, but through consultation with our digital preservation advisor here on campus, reviewing FADGI guidelines (http://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/), Epson’s SilverFast 8 software manual, and writings and discussions across the web, and extensive testing, we made some progress.

First of all, we needed to properly calibrate our scanner for both reflective and transparency scanning. Additionally, minor adjustments to other settings in SilverFast can produce a better scan; one that is more faithful to the image than its imperfect representation as a printed photo. In the end, we arrived at settings which could be applied globally to reflective scanning, with a slight variation for transparency. These settings are being documented and will be consistently applied going forward. I will point out that the improvement with transparencies in particular, has been significant with the new settings.

Initially, I was reluctant to make changes to any settings. I was suspicious that changes to settings might alter the image, not make it more faithful to the original, as these changes definitely have. Perhaps that reflects my inexperience as much as anything, but I think that this is where the two perspectives I alluded to converge. When I think again about why we’re producing and preserving these images, I welcome any process that refreshes the dialogue and re-centers my work; that brings curatorial thinking to bear again and again on a process (like scanning images) that can easily become mechanical.

before & after (transparency scanning):

The David C. Driskell Center team has been making steady progress in its Institution of Libraries and Museum Studies (IMLS) grant’s digitization project. We’ve developed procedures and work flows for scanning archival photographs and slides. To assist with scanning of photographs, slides, and transparencies, the Driskell Center hired David Conway, a graduate student in the Master of Library and Information Science program at the College of Information Studies at UMD. We are currently working on scanning photographs from David C. Driskell’s Papers. Photographs are available for viewing on the Driskell Center website as we get them uploaded; see http://driskellcenter.pastperfectonline.com/photo.

Scanning

Photographs from the David C. Driskell Papers archives are scanned by David Conway.

My interest in preservation of cultural artifacts is what led me to pursue a career in archives. It is particularly rewarding to play a small part in bringing the history, represented in these photos, to a much wider audience.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed working with photos that not only document the history of African American art, but the lives of the people who created and supported it. Through David C. Driskell’s Papers, we spend time at early openings at the Barnett-Aden Gallery in Washington, DC (one of the first galleries devoted to exhibiting African American art), while the civil rights movement was gaining momentum in the early 1960s. We witness a coalescence of the community of artists and educators with Professor Driskell’s appointment at Fisk and visits by artists like Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden (both captured in seldom seen candid shots). This period of increased recognition culminates in photos taken during “Two Centuries of Black American Art, 1750-1950,” the groundbreaking exhibition that Professor Driskell curated at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 1976.

My work with the photographs so far has taken me through the 1970s, corresponding roughly to the first third of the 900+ photos currently included in the Papers. I look forward to the rest.

Uploading

Tamara Schlossenberg has been working on quality control and uploading photographs to Past Perfect so they will be accessible on the Driskell Center’s website.

Part of uploading and quality checking scanned photographs includes taking a close look at each details of a photograph to make sure they are rendered well on the computer, and that any pre-existing photo conditions are listed on the online record. This detail allows me to see the textures of the photograph in a new way and to better appreciate the process of photography. It has also made me wonder where the line between artistic photography and archival or candid photography lies. What if the candid photograph is taken by a famous artist? Or if the photograph, despite maybe not being a high a quality print, shows that attention to subject, angle and lighting was all taken into account? There is a photo in the collection that was sent to David Driskell by Earl Hooks of seagulls amongst a trash dump. The photo stands out from the others in the collection as it isn’t clearly documenting a moment or event in David Driskell’s life, like most of the photographs in the Driskell papers. The faded photograph, taken by Earl J. Hooks on a 1971 trip to Maine, seems to be a more artistic framing the birds.

There are many clearly thought out and posed portraits in the collection, as well, some that were used for articles and publicity, as indicated by notes on the photographs. Within the Driskell papers photographs there are many beautiful and aesthetic photographs even if they weren’t intended to be art.

The David C. Driskell Center’s Digitization project photography is in full swing. The Driskell Center is continuing to photograph its art collection. For the last few photography sessions, I have been assisting in handling the art pieces and learning all I can from Greg Staley, a professional art photographer hired for this project, about the photography process.

There is an old saying in photography, that it is just “point and shoot.” This couldn’t be further from the actual process. Our photography spaces have included our prep room as well as the gallery, both of which were repurposed into a makeshift photography studio with lights, backdrops, and any props to hold up the piece. There are certainly some more tricky pieces to shoot. A piece from our latest exhibit, The Last Ten Years: In Focus, Serious Play by Tarrence Corbin was difficult to shoot because of the sheer size of the piece. In its frame, the piece is about six and half by seven feet. It took twice as many lights as usual to get even lighting.

For the most part two-dimensional pieces are fairly easy to photograph once lighting is set up. Three-dimensional pieces are a little trickier to photograph. Because they produce shadows, the lighting has to be set up not just to illuminate the piece but also so there is minimal shadows in the final image. With 3 dimensional pieces, multiple angles of the piece have to be photographed, as well. Some pieces are more visually complex than others, like Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Peace Halting the Ruthlessness of War. The piece features a horse and rider over a mass of humans who all appear to be in despair. The rider of the horse holds a staff that has a face in despair on it. The complexity of the piece makes it interesting to look at and try to analyze. It also meant that extra time was spent deciding what sides and angles should be photographed to make sure the entirety of the object was recorded.

(Above) Side view with the rider’s face towards viewer. (Below) Reverse view of sculpture with head on staff visible.(Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Peace Halting the Ruthlessness of War, 1917, Bronze cast sculpture, © Dr. John L. Fuller, Sr, 2017. Photography by Greg Staley, 2017. 2008.04.012)

A sculpture Boy on a Stump by Augusta Savage was another challenging piece. The artwork is a solid bronze sculpture standing almost three feet high, and as such is extremely heavy. Based off of rough calculations, it could weigh about 1600 lbs. It was too heavy to move with just one or two people, and required three people to work together to load the sculpture onto a standing dolly to move it. It then took two people to move the dolly; one to push the sculpture and another to hold it steady and guide the dolly. The sculpture ultimately had to be photographed in the art storage vault standing on the floor. White boards were laid out so the color under the statue was neutral, and to protect the artwork. The piece was also photographed from three different angles, and had to be turned to shoot each one. It took almost an hour and half to shoot the one piece.

As we move along with the project, I am learning more about the photography process, especially since we recently purchased a high-quality camera for the Driskell Center. Not only are the sessions with Greg allowing us to get high resolution images of the current collection, but we are using them as a training ground to creating a manual to detail the technical aspects of photographing artwork so that we can continue the process as we receive new pieces in the future. All the high-res images from the digitization project are available from the Driskell Center upon request.

Post written by Tamara Schlossenberg, a graduate assistant working on the ILMS grant project.

Exciting things are happening at the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora. The Driskell Center received a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) for the Driskell Center Digitization Project which began in September this year. This grant provides the Driskell Center funding to digitize the entirety of the Center’s art collection as well as part of the archives collections, including 150 audio tapes, 90 videos, 1,500 photographs, 3,500 slides, and select documents. The goal of this project is to preserve records and artwork owned by the Driskell Center, some of which are fragile, irreplaceable, and on outdated formats, further making these unique materials accessible to the public and researchers. Additionally, the Driskell Center team is writing digitization procedures and standards that will allow for digitization projects to continue in the future and will ensure sustainability.

So far, the process of photographing the art collection has begun, starting with the current exhibition, The Last Ten Years: In Focus which highlights selected paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, and mixed media acquired by the Driskell Center in the last ten years as well as highlights from the archives. It’s a beautiful exhibition which showcases the broadness of the Driskell Center’s collections and I highly recommend that you will visit us to see it before it closes on November 17th.

As we digitize the collection, I have been researching and compiling information that will be helpful for creating the digitization standards and procedures. There has been a lot of work comparing the standards for other institutions and understanding the unique needs of the Driskell Center.

I, Tamara Schlossenberg, am the Graduate Assistant hired to work on the project. I am a first year graduate student in the dual Masters of Applied Anthropology and Masters of Historic Preservation with a focus in Archaeology. I got my Bachelor’s in Art and Archaeology with an Archaeology concentration from Hood College in 2016. I have served as an intern at The National Museum of Civil War Medicine and the Jewish Museum of Maryland, and hope to go into collections management.

Over the next two years it should be an interesting process as we continue to digitize the Driskell Center’s collections. During this time, be on the lookout for new blogs posts about the digitization process and highlights from the collection.

To learn more about the Driskell Center Digitization Project, see the press release here.

There has been a lot of progress happening in the David C. Driskell Archives recently. Our Graduate Assistant Molly has been hard at work going through one of the final series which focuses on David C. Driskell’s personal life including various journal entries, personal correspondences, and keepsakes. This is a fascinating part of the Driskell Papers and in a few weeks, Molly will be writing a post about some of the interesting things that she’s found while processing that series. In addition, I’ve been working through some of the video materials which include reel-to-reel films and VHS tapes of lectures by David C. Driskell, awards ceremonies in which he was honored, and various programs he appeared in or helped produce. We are looking forward to having those all cataloged before the holiday season.

One of the latest activities related to the Driskell Archives has been working with Prof. Driskell in person so that he can provide information about the several thousand photographs in his collection. Though Prof. Driskell already donated and transferred some photographs to the Driskell Center, the majority of them are still held by him, and there are a lot! Our first priority is working with Prof. Driskell and his daughter Daphne Driskell-Coles to identify the thousands of photographs that will be part of the Driskell Papers collection. This past week, I went to Prof. Driskell’s home Maryland to help identify photographs and to begin the photograph inventory. I’m hoping to be able to work with them often over the next few weeks so that we can begin really working with and arranging the photos to make them available for researchers.

Sitting with Prof. Driskell was fascinating as always —for many photos that we went through together, he had a story to tell and could identify who was in the photo and when and where it was taken.

The acquisition of these photographs is an exciting project and we’re looking forward to delving into them more, sharing the project with you, and allowing researchers to integrate the photographs into their research on African American art!

In addition to this exciting project, I wanted to share a video that was created by the University of Maryland about the David C. Driskell Center and the great things that we do here! You can view the video here:

All of us here at the Driskell Center are wishing you and yours a very Happy Thanksgiving!

This post was written by Stephanie Maxwell, Archivist at the David C. Driskell Center Archives.

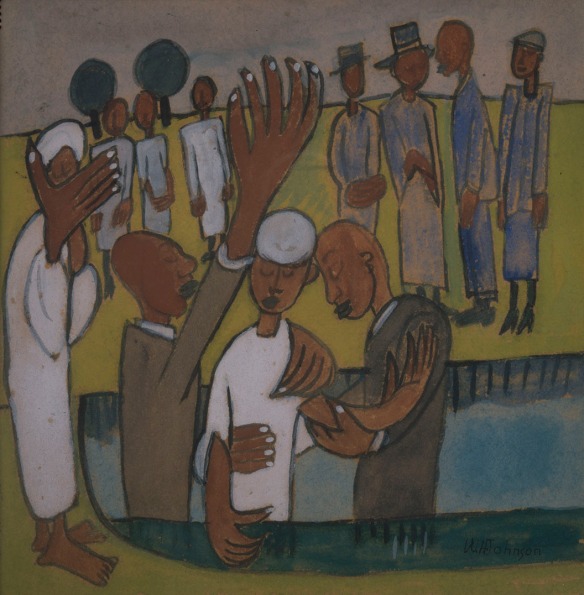

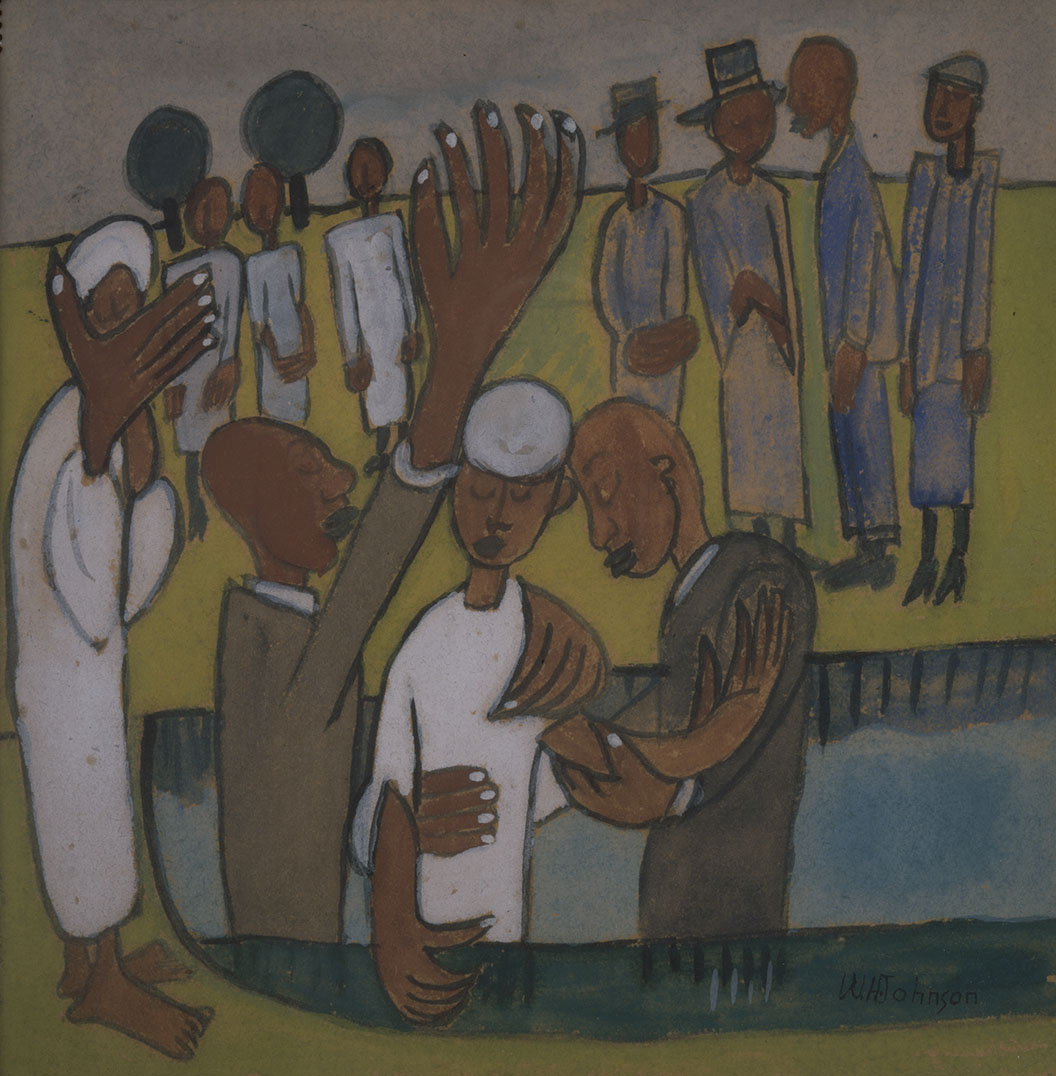

Two weeks ago, the Driskell Center celebrated the opening of the important exhibition Robert Blackburn: Passages which is open to the public in the gallery until Friday, December 19, 2014. The opening reception was a wonderful event, welcoming guest speakers Faith Ringgold and Mel Edwards and allowing the friends of the Driskell Center to admire the works of Robert Blackburn, an artist previously unrecognized for his contribution to American art. The exhibition is wide-ranging and represents not only Robert Blackburn’s work, but also an additional thirteen works by Blackburn’s colleagues—including teachers, friends and students.

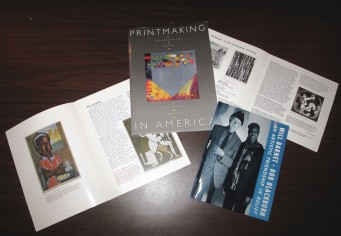

As I mentioned in my last post, there is no correspondence in the Driskell Papers between Blackburn and David C. Driskell. Though there is no display as we have traditionally done in the past for exhibitions, the research component of the Driskell Center is represented in an exciting, interactive way. Throughout the run of Robert Blackburn: Passages, visitors will be able to sit and browse through a selection of books on printmaking and Robert Blackburn, presented on a table in the center of the gallery. These books and pamphlets were pulled from the Driskell Center Library which is housed in a room within the Driskell Center office space. The display in the gallery includes two books from the Driskell Center’s Library collection including Printmaking in America: Collaborative Prints and Presses, 1960-1990, Will Barnet / Bob Blackburn: An Artistic Friendship In Relief , and two pamphlets Robert Blackburn: Master Artist – Master Painter, Detwiller Visiting Artist February 27-March 27, 1994 and Campaign for Robert Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop. Interested visitors can leisurely browse through these books and learn more about printmaking and Robert Blackburn as an artist and mentor.

David C. Driskell Center. Catalogues and books available for viewing during the “Robert Blackburn: Passages” exhibition. Fall 2014.

The Library’s collection of roughly 4,000 books has been collected over the course of 12 years by the Driskell Center staff and also includes selections from Prof. Driskell’s personal library as well as from Dr. Robert Steele’s personal library. This collection of resources reflects the research needs and purposes of the Driskell Center. The collection of books, exhibition catalogues, journals, and magazines focuses on African American art, American art, artists, and art history, following the mission of the Center. The Driskell Center staff has been using this collection to inform research and publicity for developing its exhibitions, collections, and scholarly events; it is a generally useful resource, which we wanted to share with our visitors as well.

Currently, our staff is working to catalog these books and make their records available and searchable to the public through our PastPerfect website. Books are cataloged under “Library” and can be found through keyword searches in the online search function here. More books are being added to the catalog every week, so continue to check back for updates! The non-circulating Library is open to researchers by appointment during office hours Monday-Friday.

Visiting the Driskell Center to see the Robert Blackburn: Passages exhibition is worth finding the time for, and we hope that you’ll come and learn a little about printmaking and the impact that Blackburn had on the art community!

This post was written by Stephanie Maxwell, Archivist at the David C. Driskell Center Archives.

Summertime at the Driskell Center, though always busy, seems to have something missing due to the empty gallery space. I always look forward to the fall semester when I get to walk past the gallery every day and see the wonderful works on display. As works on loan for the exhibition Robert Blackburn: Passages have arrived to the Center, and our intrepid staff begins hanging them, it inspired me to take a look into the Driskell Papers and see what the collection holds about Robert Blackburn and The Printmaking Workshop which he founded in New York City 1948.

Robert Blackburn was an artist in his own right, and this exhibition is the first comprehensive retrospective of his work. The exhibition will feature 100 works by Blackburn, as well as a few additional works by his colleagues–teachers, artists, and friends. After doing additional reading about Blackburn, it is very clear that Blackburn influenced, worked with, and helped many artists, among them Romare Bearden, Grace Hartigan, and Robert Rauschenberg.

Though there is no correspondence in the Driskell Papers between Prof. Driskell and Blackburn, Prof. Driskell did keep informational material about The Printmaking Workshop and about Blackburn himself. I found some interesting documentation including a brochure that Prof. Driskell kept about this unique and groundbreaking space created by Robert Blackburn. The brochure has some great facts and outstanding photographs (taken by Ryo Watanabe and Eric Maristany) that showcase The Printmaking Workshop and the great work that Robert Blackburn did for the art community.

The exhibition Robert Blackburn: Passages opens with a reception on September 18, 2015 from 5-7PM; the exhibition is open until December 19. The Driskell Center also produced a 144 page catalogue for this show which will be available for sale at the Center as well as on-line beginning September 18, 2014 (please check back here to purchase online after that date). For more about the exhibition, please visit our website. If you are interested in learning more about Blackburn, the Library of Congress holds the records of The Printmaking Workshop in their manuscript collection.

This post was written by Stephanie Maxwell, Archivist at the David C. Driskell Center Archives.

It’s been a while since I’ve posted to the blog, but so many things are happening here in the David C. Driskell Center Archive that it’s been hard to keep up! Here is an update on what is new in the Archives.

Over the past few weeks, we have gotten some new windows in the Driskell Center which kept us busy packing up the boxes that hold the Driskell Papers and storing them in our conference room so that they are protected from the construction. Though we still have access to the boxes, we’re hoping to get them back in the Archive in the next few weeks.

One of our Graduate Assistants, Nick Beste, has found a full time job as an Archivist in Arkansas where he’ll be processing collections for the National Park Service. We had to say goodbye to him a few weeks ago, but we know that his time at the Driskell Center prepared him for life as a professional Archivist and we wish him all the best! Before he left, though, Nick worked hard to process Series 10: Audio and Video Materials, Sub-Series 1: Audio Recordings. This sub-series includes cassette tapes, minicassettes, and audio reels that are recordings of David C. Driskell’s lectures and interviews. In the coming months, we will also be processing Series 10: Audio and Video Materials, Sub-Series 2: Video Recordings which includes VHS tapes and reel-to-reel films of interviews, lectures, colloquia, and films that have accompanied exhibitions. The potential of these materials is great and we are looking forward to delving into this sub-series more.

Though Nick has moved on, our other Graduate Assistant, Molly Campbell, has been hard at work. Since the last blog post, Molly has completely processed all of Series 2: Educator which focuses on Prof. Driskell’s life as a professor, mainly at Fisk University and the University of Maryland, though he also held adjunct and shorter-term positions at various universities around the world. This series is made up of five sub-series including: Sub-Series 1: Fisk University, Sub-Series 2: University of Maryland, Sub-Series 3: Other Institutions, Sub-Series 4: College and University Catalogs, and Sub-Series 5: Miscellaneous. These records are available on PastPerfect online and are open for research.

Another exciting project that has gained some traction this summer is the cataloging of the Driskell Center’s research library collection into PastPerfect. The Driskell Center has an extensive library of over 2,000 books, exhibition catalogues, and journals which focuses on African American art and culture and is constantly being updated. This resource is a valuable one for researchers whose interests coincide with the Driskell Center’s mission. Previously, the records of these books were kept in an Access database, available only to the Driskell Center staff. The staff has since decided to catalog them in PastPerfect, thereby making the records available online. This project is ongoing and new records will be made available through PastPerfect online each week.

As summer is getting to its peak, we are looking forward to meeting some of our processing goals and preparing for the fall which will include an Archives display accompanying the exhibition Robert Blackburn: Passages which opens on Thursday, September 18, 2014.

Look for a post in the coming weeks about some of the interesting things we are finding in the series that Molly is now working on (Series 1: Personal) and more updates!

This post was written by Stephanie Maxwell, Archivist at the David C. Driskell Center Archives.

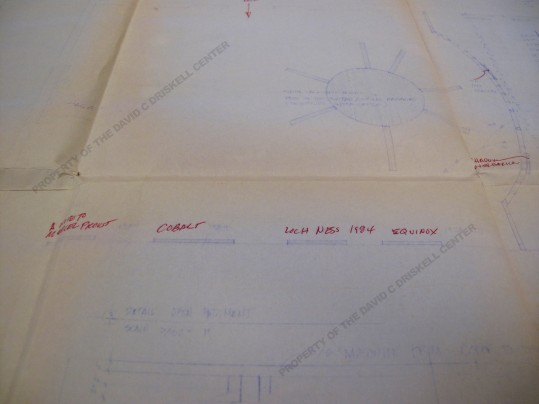

Oftentimes, the most interesting things that we come across in the Driskell Papers are things that are a little out of the ordinary. As I was processing Series 3: Exhibitions, Sub-Series 3: Curated by David C. Driskell, I came across quite a few of these unique items; my favorite among them is a blueprint from the exhibition Contemporary Visual Expressions: The Art of Sam Gilliam, Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Keith Morrison and William T. Williams. This exhibition was curated by David C. Driskell in 1987 for what was then the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, now the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. The exhibition ran from May 27-July 31, 1987 and was the first exhibition to show in the museum’s newly renovated building which added a level of importance to the opening events and the show itself.

The exhibition focused on the work of four artists: Sam Gilliam, Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Keith Morrison, and William T. Williams and Prof. Driskell curated the exhibition keeping in mind the urban environments of the artists: Gilliam, Jackson-Jarvis, and Morrison were Washington, DC-based, and Williams was New York City-based. As Prof. Driskell wrote in his Introduction for the exhibition catalogue: “This exhibition does not present itself thematically, nor does it represent all the myriad approaches with which these individual artists experiment. But these artists represent the soul of their urban environments, Washington, D.C. and New York City, and transform events and ideas to enliven our artistic sensibilities and contribute to our own understanding and development.” (Draft of Contemporary Visual Expressions Exhibition Catalogue by David C. Driskell (ca. 1987): Box 3, Folder 6, Page 12. David C. Driskell Papers: Exhibitions – Curated by David Driskell, David C. Driskell Center Archive.) The artists’ connections with their hometowns made this exhibition all the more meaningful.

The Driskell Papers contain many correspondences between the artists and Prof. Driskell and many programs, exhibition catalogue drafts, and artist information from Contemporary Visual Expressions. What made me excited, however, was this blueprint that represents the proposed layout of the exhibition. Though the document has faded over time, you can still make out the details which include the shape and description of a spiral sculpture from Martha Jackson-Jarvis, the names and locations of some of the artwork on the walls, and details of the floor plan for this exhibition hall in the then-new building.

Photo of blueprint for “Contemporary Visual Expressions” exhibition (March 4, 1987): Box 2, Folder 12. Driskell Papers: Exhibitions – Curated by David Driskell, David C. Driskell Center Archive.

Detail of blueprint for “Contemporary Visual Expressions” exhibition showing sculpture installation plan for Martha Jackson-Jarvis and planned locations for some of William T. William’s artwork (March 4, 1987): Box 2, Folder 12. Driskell Papers: Exhibitions – Curated by David Driskell, David C. Driskell Center Archive.

There are other blueprints in this series that delve deeper into the plans for the renovation of the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, but this particular one is the most interesting. Along with the related correspondence and project plans, this blueprint shows Prof. Driskell’s process of contemplating and presenting the works in the gallery and the artists’ and their works’ relationship to one another.

To see what else we have in the Driskell Papers about Contemporary Visual Expressions, see our PastPerfect website.

This post was written by Stephanie Maxwell, Archivist at the David C. Driskell Center Archives.

Published at

100vw, 584px”></a></p>

<p id=) David C. Driskell at his home helping to identify photographs in his collection. Credit: David C. Driskell Center Archive. November 19, 2014.

David C. Driskell at his home helping to identify photographs in his collection. Credit: David C. Driskell Center Archive. November 19, 2014.

100vw, 584px”></a></p>

<p id=) David C. Driskell working to identify photographs in his collection. Take notice of the shelf to the right–those are mostly full of photographs! Credit: David C. Driskell Center Archives. November 19, 2014.

David C. Driskell working to identify photographs in his collection. Take notice of the shelf to the right–those are mostly full of photographs! Credit: David C. Driskell Center Archives. November 19, 2014.

: Box #, Folder #. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.</p>

<p>” data-medium-file=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop0011.jpg?w=300″ data-large-file=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop0011.jpg?w=584″ class=”wp-image-390 size-medium” src=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop0011.jpg?w=300&h=207″ alt=”Front of pamphlet on The Printmaking Workshop (undated): Box 4, Folder 15. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.” width=”300″ height=”207″ srcset=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop0011.jpg?w=300&h=207 300w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop0011.jpg?w=600&h=414 600w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop0011.jpg?w=150&h=104 150w” sizes=”(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px”></a></p>

<p id=) Front of pamphlet on The Printmaking Workshop (undated): Box 4, Folder 15. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.

Front of pamphlet on The Printmaking Workshop (undated): Box 4, Folder 15. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.

: Box #, Folder #. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.</p>

<p>” data-medium-file=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=300″ data-large-file=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=584″ class=”wp-image-389 size-large” src=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=584&h=202″ alt=”Inside of pamphlet on The Printmaking Workshop (undated): Box 4, Folder 15. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.” srcset=”https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=584&h=202 584w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=1165&h=404 1165w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=150&h=52 150w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=300&h=104 300w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=768&h=266 768w, https://driskellcenterarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/printmakingworkshop_combined_inside.jpg?w=1024&h=355 1024w” sizes=”(max-width: 584px) 100vw, 584px”></a></p>

<p id=) Inside of pamphlet on The Printmaking Workshop (undated): Box 4, Folder 15. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.

Inside of pamphlet on The Printmaking Workshop (undated): Box 4, Folder 15. Driskell Papers: Artists and Individuals, David C. Driskell Center Archives.